Anne Boyer in The New Yorker:

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

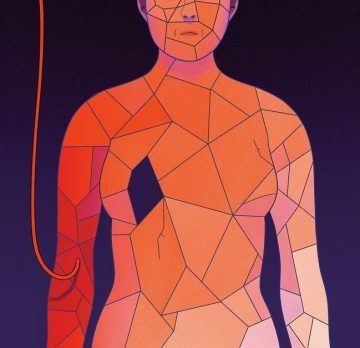

Later, when I was sick, I was on a chemotherapy drug with a side effect of endless crying, tears dripping without agency from my eyes no matter what I was feeling or where I was. For months, my body’s sadness disregarded my mind’s attempts to convince me that I was O.K. I cried every minute, whether I was sad or not, my self a mobile, embarrassed monument of tears. I didn’t need to build the temple for weeping, then, having been one. I’ve just always hated it when anyone suffers alone. The surgeon says the greatest risk factor for breast cancer is having breasts. She won’t give me the initial results of the biopsy if I am alone. My friend Cara, who works for an hourly wage and has no time off, drives out to the suburban medical office on her lunch break so that I can get my diagnosis. In the United States, if you aren’t someone’s child or parent or spouse, the law does not guarantee you leave from work to take care of them.

As Cara and I sit in the skylighted beige of the conference room, waiting for the surgeon to arrive, Cara gives me the small knife she carries in her purse so that I can hold on to it under the table. After all these theatrical prerequisites, what the surgeon says is what we already know: I have at least one cancerous tumor, 3.8 centimetres in diameter, in my left breast. I hand the knife back to Cara damp with sweat. She then returns to work.

No one knows you have cancer until you tell them.

More here.