Geoffrey Wildanger in the Boston Review:

Geoffrey Wildanger in the Boston Review:

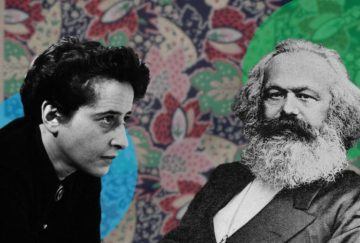

The essence of Arendt’s disagreement with Marx is the importance she places on the question of political rights above social ones. She develops this priority most extensively in On Revolution (1963). Elizabeth Young-Bruehl, her biographer, cites a review by Michael Harrington, who would go on to found the Democratic Socialists of America, as representative of the Marxist reception. Though he accepts the arguments of the latter half of the book, with its praise of Rosa Luxemburg’s “council communism,” Harrington rejects the argument upon which Arendt’s praise rests: the priority of political rights over social amelioration. In our post-Occupy era, the starkness of Arendt’s dichotomy may strike us as exaggerated, yet she stuck to it. Late in life, when her friend Mary McCarthy asked her why certain social matters could not simply be defined as rights (health care, say), she dodged the question. For Arendt, the fundamental distinction is between the private and the public spheres. Attempting to politicize the private, she believes, will more likely subjugate politics to economics than vice versa.

As in her conversation, Arendt’s writing on social concerns is often characterized by defensiveness, yet she does criticize capitalism. This volume is a boon to those interested in her idiosyncratic thought on economic matters, in particular her distance from both socialist and free market thinkers. According to his dialectical model of history, Marx thought capitalism would create its own gravediggers. Arendt doubts any such tendency to self-destruction, and thus she finds nothing dialectically redeemable about the violence of the marketplace. While a free market would totally colonize the space of political action, Arendt also argues that total expropriation is “hell.”

More here.