by Joshua Wilbur

tl; dr:

Skim-reading is a bad habit, all things considered.

It’s detrimental to our sense of time and place. Screen technologies are fundamentally changing not only how we read but also how we think and what we remember.

But readers shouldn’t take all the blame. Writers, editors, and creatives of all stripes must adapt in order to counteract our tendency to skim-read everything in sight.

For the uninitiated, “tl; dr” stands for “too long, didn’t read.” It’s a handy piece of internet slang, used on discussion forums to briefly summarize a dense “wall of text.” A good tl;dr distills the key points of a lengthy post, saving the hurried reader minutes of time.

It’s not unlike the BLUF (bottom line up front) technique commonly used in business and military writing, in which “conclusions and recommendations are placed at the beginning of the text, rather than the end, in order to facilitate rapid decision making.”

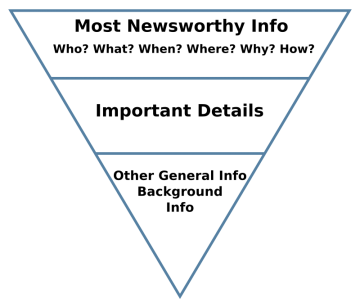

You could also imagine tl;dr as the internet’s snarkier version of the Inverted Pyramid method used by journalists. The method dictates that the most significant information should appear at the top of any news article —front and center— with supporting details falling below. To “bury the lead” is to fumble the pyramid’s orientation and waste the reader’s time as a result.

Arguably, tl; dr is only the latest expression of an old petition from readers: get to the point; give me the gist; just the facts, ma’am. We’ve always been pressed for time and concerned with the most salient points, especially when it comes to the news. For many of us, “reading the newspaper” has long amounted to skimming the headlines.

So what’s the big deal?

The problem, of course, is that we’ve become serial skim-readers, always flitting from paragraph to paragraph, article to article, app to app. In our attempts to keep up with the world, we prioritize quick hits of information over sustained understanding.

In one of the Guardian’s most shared pieces of 2018, Maryanne Wolf, an expert on the neuroscience of reading, described the pernicious effects of screen-reading and skim-reading, which go hand in hand.

In her essay, Wolf surveys the current research on screen/skim-reading. She points to reduced comprehension when quickly browsing texts, a troublesome erosion of deep-reading processes among younger people, and a general “atrophy of critical analysis and empathy” amid a “constant bombardment of information.” Multiple studies bear out what may seem obvious: digital screens diminish our capacity to appreciate complexity.

I was especially struck by Wolf’s description of the work of three researchers— Karin Littau, Andrew Piper, and Anne Mangen. Wolf writes:

“Piper, Littau and Anne Mangen’s group emphasize that the sense of touch in print reading adds an important redundancy to information – a kind of “geometry” to words, and a spatial “thereness” for text. As Piper notes, human beings need a knowledge of where they are in time and space that allows them to return to things and learn from re-examination – what he calls the “technology of recurrence”. The importance of recurrence for both young and older readers involves the ability to go back, to check and evaluate one’s understanding of a text. The question, then, is what happens to comprehension when our youth skim on a screen whose lack of spatial thereness discourages ‘looking back.’ ”

I’ve certainly felt this lack of “spatial thereness” when reading digitally, a sense of not being rooted to what I’m reading.

Often, I’ll sprint through a series of articles, and, along the way, I’ll save things to “look back” to later. But since there’s always fresh material to skim over, I rarely review yesterday’s news. And because our devices encourage accelerated, repetitive action — scroll, scroll, scroll; tap, tap, tap; hurry, hurry, hurry; read, read, read — everything ultimately blurs together.

This manner of reading — briskly, skimmingly — conflates totally disparate texts into a single stream, so that the screen becomes a great equalizer of informational sources. On my phone, I might skim a painstakingly reported New Yorker piece just as I would a sports report or a friend’s Facebook post or a lengthy email.

What’s worse, I frequently form opinions while skim-reading. A headline alone might influence my views. Later, I’ll talk to a friend, vaguely, about a news topic, maybe something to do with Brexit or an upcoming election. But do I really understand what’s happening? Could I speak to the details? Or did I merely skim an article or two?

And yet we must come to a decision about how to spend our reading hours. What good is it to read something familiar, or something uninteresting, or something dryly written? Skimming allows us to “maximize” our free time. Once I find something worth reading closely, I’ll slow down and focus.

It’s clear, then, that the “rub of time,” to borrow a phrase from Martin Amis, is at the heart of the skim-reading habit. We skim because we’re in a hurry—perhaps during a much-needed break from work or other demands—and we think it best to be selective about our reading. We skimp here (scanning or even skipping our way through a text) to gain over there, where the truly interesting fact or anecdote lies. In this way, skimming is often an efficient means of identifying what really matters and getting to the heart of a subject.

Still, I can’t help but feel that all this skimming undermines our ability to make sense of things. Skim-reading is a wonderful way to satisfy what Ian Leslie calls “diversive curiosity” in his 2015 book, Curious: The Desire to Know and Why Your Future Depends on It. This type of curiosity is expansive, sprawling over many subjects but hardly cracking the surface. It’s the curiosity of the fox, the dilettante, the jack-of-all-trades. Better, perhaps, to cultivate what Leslie calls “epistemic curiosity,” a curiosity of deep knowledge, like that of the hedgehog, who knows one important thing. I doubt anyone has skimmed their way into wisdom.

So what should be done?

Most obviously, we can change our own behavior as individuals: slow down, seek out less, appreciate more. (tl; dr: stop and smell the roses). It’s probably better to read one thing well than three things skimmingly. If I don’t remember what I’ve read, and if it isn’t lodged somehow in my emotional unconscious, then was it worth skimming at all?

We know that memory is a dynamic process that’s tied to our bodily senses. You’ll retain more of what you read if you introduce some form of novelty to the equation, ideally something that activates your senses. Try reading in a strange place. Better yet, light a fragrant candle, play a whimsical song, or even eat a madeleine if you like.

I’m half-joking, but I do think we should shift from reading for information to reading for experiences. Experiential, as opposed to informational, reading is the only way to compete with the array of entertainments and distractions available to us. It’s become as important to think about how we read as what we read.

Of course, fiction has always satisfied this itch for experience. And fiction cannot be readily skimmed because stories require narrative coherence and the necessary development of plot and character. Made-up stories are difficult to predict—when they aren’t, we criticize them—and function to entertain. Most importantly, we don’t know what’s going to happen in fiction. So we spend countless hours with novels, films, and TV shows, while, on the other hand, we skim a two-thousand word article about global warming, a real-life story that (we think) we know too well.

This is where writers, journalists, editors, graphic designers, programmers—anyone invested in the wide world of non-fiction writing—must step up to the plate. To counteract skim-reading and win back our attention, “content creators” (the term makes me cringe) should aim to surprise readers in easily-digestible ways, preferably with some form of narrative momentum.

For example, it’s often beneficial to “write short.” Roy Peter Clark, the author of How to Write Short: Word Craft for Fast Times, argues that “in the digital age, short writing is king.” As Clark puts it, “[a] time-starved culture bloated with information hungers for the lean, clean, simple, and direct.” Verlyn Klinkenborg, who sat on the editorial board of the New York Times for many years, agrees about the value of writing short, as expressed in his excellent book Several Short Sentences About Writing.

In imitation of his argument, Klinkenborg (always with great economy) suggests that short sentences and short paragraphs hold a reader’s attention. They sustain a piece of writing with rhythm and clarity. Short writing is too quick and too clever to skim.

Long paragraphs and long sentences, on the other hand, can be a drag to read, inundating readers with unnecessary information and losing their attention spans in the process, especially when long sentences or long paragraphs don’t actually say much or contribute anything of substance or include redundancies. It’s perhaps worth wondering if—like a tree falling in the woods with no one around and thus making no sound —a sentence lost in the middle of a long paragraph actually exists when no one is there to read it. In any case, it’s clear that long paragraphs encourage skim-reading because who wouldn’t want to skip past something that exists primarily to contain the indulgences of the writer himself?

All that said, many (especially those writing for the traditional newspapers) adhere to Clark’s and Klinkenborg’s “write-short” credo. And still people skim-read. Something more is required in order to compete with visual media.

“If you can’t beat them, join them” say visual stories, which incorporate text and image to create memorable (often interactive) reading experiences. The New York Times, NPR, CNN, and other outlets increasingly lean on visual stories because they blend more seamlessly into the digital landscape with which “users” (rather than “readers”) are comfortable. Visual stories are an attractive, modern upgrade to the tradition of black text against a white background.

What’s more, visual stories often dictate a user’s experience in ways that prevent skim-reading. Consider this piece on internet privacy from the NYT’s Farhad Manjoo. In order to progress through the story, you must click to advance: perhaps an ironic form of control in an essay about civil liberties, but it’s an effective device. Manjoo, in a clever article appearing six years ago on Slate entitled “You Won’t Finish This Article,” wrote about the problem of skim-reading online. Now, his visual story incorporates the clever solution of forcing the reader’s hand. If you won’t slow down and pay attention, then the platform will make you.

It’s understandable to feel ambiguous about the evolution of reading. I suspect that more radical changes are on the horizon with the development of virtual and augmented realities and the coming ascendancy of a generation raised on memes. And, in the face of transformation, it’s tempting to retreat to the safety of the written word and its traditional strengths. “Write something so good and interesting that they’ll have to read it,” we want to say. A noble pursuit, but if the double-sided coin of reading and writing is to maintain its value in the world, then our engagement with words will almost certainly need to adapt or die. We’re likely headed for a strange future, but I suspect that deep-reading can be salvaged if people are sufficiently creative (shouldn’t be a problem) and properly incentivized (much harder).

Perhaps, in the end, we’d all benefit if publications simply published less for us to read. This may sound like a counterintuitive suggestion, but, if there were less content in the world, then the problem of excess— too much to read and not enough time— would be mitigated. Problem solved.

But, of course, it’s an absurd idea. The Pandora’s box of endless information to digest can never be closed and will only spew forth words and images at an accelerated rate. We must decide where and how to focus, or risk skimming ahead in a state of perpetual confusion.