Claudia Rankine and Will Rawls – What Remains, 2019.

“… a collaborative performance that responds to questions of presence by poetically addressing the erasure and exposure that drives the historical disturbance of black citizens.”

by Emily Ogden

The author learns to like it loud.

A friend of mine has an expression he uses when he isn’t wild about a book, or a show, or an artist. For people who like this sort of thing, he’ll say, this is the sort of thing they like. He’s giving his irony-tinged blessing: carry on, fellow pilgrims, with your rich and strange enthusiasms.

My friend is saying something, too, about being imprisoned by our tastes—or by our conscious ideas about our tastes, anyway. There I am, liking the sort of thing I like. How tiresome. Isn’t there some way out of this airless room? Trapped with our own preferences, we find we don’t quite like those things after all—we don’t like only them, we don’t like them unfailingly. Taste not a duty we can obey, nor will it obey us. It wells up from somewhere. It comes in through the side door. It is, at its best, a surprise.

I don’t like loud music. That at any rate has been the official word for some years. There was reason for doubt. In high school I listened to Nine Inch Nails in my pink-and-cream-colored bedroom, tracking the killer bees of The Downward Spiral as they veered from the right to the left headphone. Later, Venetian Snares drove me out of myself when that was what I needed. (If you don’t know the music of Venetian Snares, it is tinny, relentless, almost intolerable, highly recommended.) Nothing has ever been better than hearing Amon Tobin’s waves of musical and found noise at Le Poisson Rouge in New York, more or less alone. My tolerant friend came along but gently left me to myself after a while, perhaps because being in that basement club felt something like participating in a sonic weapon test. Could the sheer percussive force of a sound wave alter the rhythm of your heart? It seemed as though it might. I was ready to pay the price, and so were a lot of other people I saw standing rapt, alone, looking up. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Thomas O’Dwyer

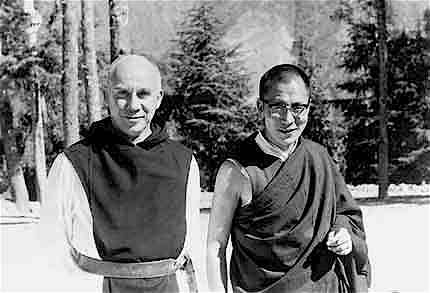

“There is no question I love her deeply … I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day with her, our bottle of champagne … She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other’s love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, ‘I am happy, I am at peace now.’ And so was I.”

These romantic diary entries of a middle-aged man smitten with a new love would seem unremarkable, commonplace, but for one thing. The author was a Trappist monk, a priest in one of the most strict Catholic monastic orders, bound by vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and silence. Moreover, he was world famous in his monkishness as the author of best-selling books on spirituality, monastic vocation and contemplation. He was credited with drawing vast numbers of young men into seminaries around the world during the last modern upsurge of religious fervour after World War II. Two years after this tryst, the world’s most famous monk was found dead in a room near a conference centre in Bangkok, Thailand. He was on his back, wearing only shorts, electrocuted by a Hitachi floor-fan lying on his chest. In the tabloids there were dark mutterings of divine retribution, suicide, even a CIA murder conspiracy.

So passed Thomas Merton, who shot to fame in 1948 when he published his memoir The Seven Storey Mountain. It was the tale of a journey from a life of “beer, bewilderment, and sorrow” to a seminary in the Order of Cistercians of Strict Observance, commonly known as Trappists. A steady output of books, essays and poems made him one of the best known and loved spiritual writers of his day. It also made millions of dollars for his Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Gethsemani in Nelson county, Kentucky. Because of him, droves of demobbed soldiers and marines clamoured to become monks. Read more »

by Joshua Wilbur

tl; dr:

Skim-reading is a bad habit, all things considered.

It’s detrimental to our sense of time and place. Screen technologies are fundamentally changing not only how we read but also how we think and what we remember.

But readers shouldn’t take all the blame. Writers, editors, and creatives of all stripes must adapt in order to counteract our tendency to skim-read everything in sight.

For the uninitiated, “tl; dr” stands for “too long, didn’t read.” It’s a handy piece of internet slang, used on discussion forums to briefly summarize a dense “wall of text.” A good tl;dr distills the key points of a lengthy post, saving the hurried reader minutes of time.

It’s not unlike the BLUF (bottom line up front) technique commonly used in business and military writing, in which “conclusions and recommendations are placed at the beginning of the text, rather than the end, in order to facilitate rapid decision making.”

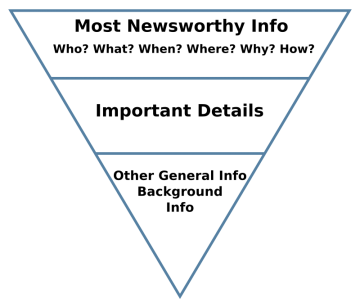

You could also imagine tl;dr as the internet’s snarkier version of the Inverted Pyramid method used by journalists. The method dictates that the most significant information should appear at the top of any news article —front and center— with supporting details falling below. To “bury the lead” is to fumble the pyramid’s orientation and waste the reader’s time as a result.

Arguably, tl; dr is only the latest expression of an old petition from readers: get to the point; give me the gist; just the facts, ma’am. We’ve always been pressed for time and concerned with the most salient points, especially when it comes to the news. For many of us, “reading the newspaper” has long amounted to skimming the headlines.

So what’s the big deal? Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

One of the earliest spring ephemerals, harbinger of spring, may be the most inconspicuous. The plant is usually no more than a few inches tall when it blooms, and if you don’t keep an eye out for it, you could walk right by and not know it’s there. Unless you kneel down and look closely, the leaves are little more than a small green patch dotted by tiny white flowers. Closer inspection reveals that the flowers have five white petals and deep red anthers, which darken with time and give the flowers a charming salt-and-pepper look. Harbinger of spring can appear as early as February, when the weather has been cold for months and the trees are bare. It’s a minute but electrifying herald of warmer and greener days to come. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

![]()

Have you ever been asked to donate to the worthy cause of sending the Lady Loins to the state semi-finals? I have, and I think I gave a couple bucks because of the doubtlessly unintentional prurience of the street fund-raising efforts of these aspiring young athletes and their lacking sign-makers.

As an editor, I think everyone needs an editor’s eye to pass over any written material, including my own. When we review our own writing, our brain fills in any lacunae in logic or syntax. This does not happen when we read other authors’ output, at least not as often. If you want to point the finger at why this occurs no matter how conscientious we are, go ahead and blame science.

You have likely seen the memes that dot social media about being able to read garbled words and sentences such as:

Tehse wrods may look lkie nosnesne, but yuo can raed tehm, cna’t yuo? [from mnn.com]

When relatively simple (one- to two-syllable words) words have their first and last letters in the correct place, our brains decipher them fairly quickly. Why does this happen? Because we rely on context to determine meaning. Whether we are counting the number of letters when we play Hangman, watching a show like “Wheel of Fortune,” or working on a crossword puzzle, our brains are analyzing the context to create solutions.

Your brain wants to fill in a pattern so that the jumble make sense. Measuring pattern recognition is one of the ways to test IQ, intelligence, and job fit (how you think being perhaps more important than what you think). According to this article from Frontiers of Neuroscience, “A major purpose of the present article is to forward the proposal that not only is pattern processing necessary for higher brain functions of humans, but [superior pattern processing] is sufficient to explain many such higher brain functions including creativity, imagination, language, and magical thinking.” Patterns and context matter tremendously.

So, what does this have to do with needing an editor forthwith? It comes down to this: You can’t be trusted. Read more »

Eiffel Tower, Paris, March of 2014.

by Jeroen Bouterse

When Socrates’ students enter his cell, in subdued spirits, their mentor has just been released from his shackles. After having his wife and baby sent away, Socrates spends some time sitting up on the bed, rubbing his leg, cheerfully remarking on how it feels much better now, after the pain.

When Socrates’ students enter his cell, in subdued spirits, their mentor has just been released from his shackles. After having his wife and baby sent away, Socrates spends some time sitting up on the bed, rubbing his leg, cheerfully remarking on how it feels much better now, after the pain.

The Phaedo, Plato’s vision of Socrates’ final conversation with his students before drinking the hemlock, is a literary piece overflowing with meaning and metaphor. Its main topic is the immortality of the soul. Socrates’ predicament provides not just the occasion but also a handy analogy: Socrates sees his death as the release of the soul from the bonds of the body (67d). His students are not so sure.

With Plato, every moral, existential and philosophical question is in the end related to a problem of knowledge. So when, in the last hours of his earthly life, halfway through Plato’s dialogue, Socrates suddenly starts off on a lecture about the epistemological paradoxes of the natural sciences, no-one is too surprised. After all, the question whether death is bad for you naturally flows into the question whether the soul can actually die, and therefore into the question what kind of thing the soul actually is, and what we can say about it and how. It is Socrates’ excursion into science that I want to zoom in on here. Read more »

by Daniel Ranard

You must have seen the iconic image of the blue-white earth, perfectly round against the black of space. How did NASA produce the famous “Blue Marble” image? Actually, Harrison Schmitt just snapped a photo on his 70mm Hasselblad. Or maybe it was his buddy Eugene Cernan, or Ron Evans – their accounts differ – but the magic behind the shot was only location, location, location: they were aboard the Apollo 17 in 1972.

Since then, NASA has produced images increasingly strange and absorbing. Take a look at the “Pillars of Creation” if you never have. Click it, the inline image won’t do. That’s from the Hubble telescope, not a Hasselblad handheld.

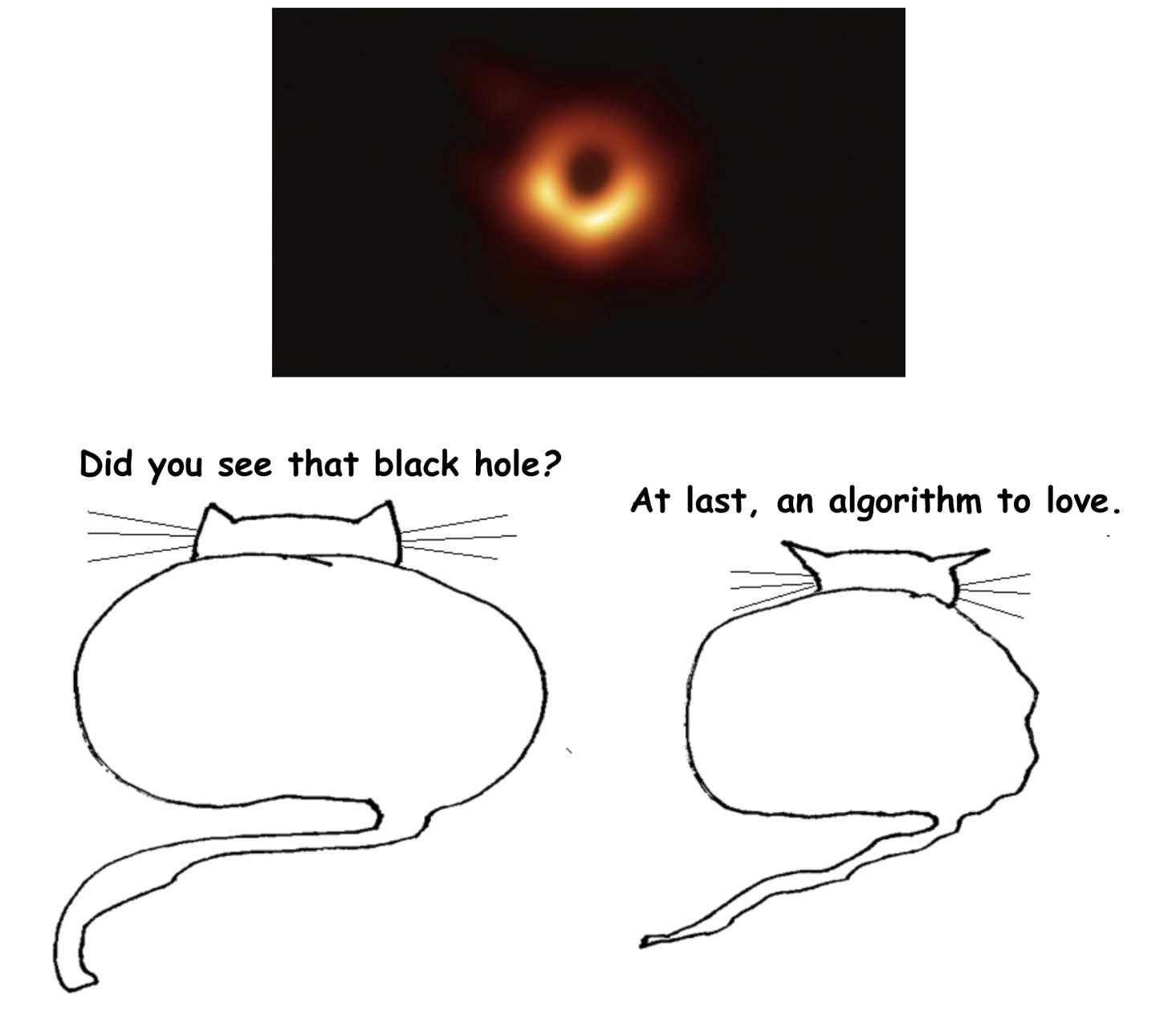

Meanwhile, this week an international collaboration gave us the world’s first photograph of a black hole. The image appears diminutive, nearly abstract. It’s no blue marble; it offers no sense of scale. Though we may obtain better images soon, the first image has its own allure. The photograph is appropriately intangible, desiring of context, not quite structureless.

Maybe “photograph” is a stretch. For one, the choice of orange is purely aesthetic. The actual light captured on earth was at radio wavelengths (radio waves are a type of light), much longer than the eye can see. The orange-yellow variations depicted in the image do not correspond to color at all: scientists simply colored the brighter emissions yellow, the dimmer ones orange. Besides, even if we could see light at radio wavelengths, no one person could see the black hole as pictured. Multiple telescopes collected the light thousands of kilometers apart, and sophisticated algorithms reconstructed the final image by interpolating between sparse data points.

Should we marvel at this image as a photograph? Or is it a more abstract visualization of scientific data? First let’s ask what it means to see a thing, at least usually. Read more »

Mateo Askaripour in Literary Hub:

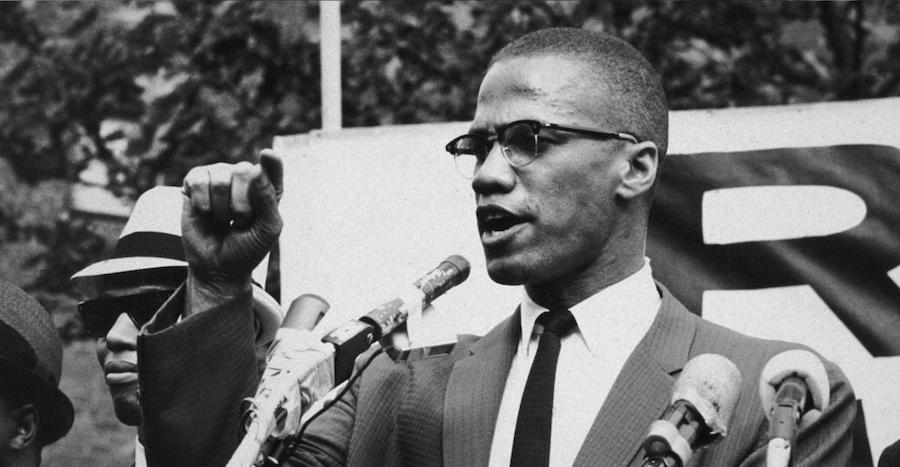

The video clip, slightly pixelated and shot in black and white, shows two men in the throes of laughter. One, white, leans closer, holding a microphone near his companion’s mouth. The other, Black, who was laughing with his head turned away, exposing a handsome set of teeth, composes himself, facing his interviewer, yet he is unable to hide his boyish smile.

The video clip, slightly pixelated and shot in black and white, shows two men in the throes of laughter. One, white, leans closer, holding a microphone near his companion’s mouth. The other, Black, who was laughing with his head turned away, exposing a handsome set of teeth, composes himself, facing his interviewer, yet he is unable to hide his boyish smile.

“Do you feel, however,” the interviewer says, “that we’re making progress in this coun–”

“No, no,” the Black man interjects, his smile giving way to a straight face as he shakes his head. “I will never say,” he continues, “that progress is being made. If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. The progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even begun to pull the knife out, much less,” he says, his smile returning, “heal the wound.” When the interviewer attempts to ask another question, the Black man declares, “they won’t even admit the knife is there.”

This video was shot in March 1964. The Black man whose smoke-like smile frequently takes new shape is Malcolm X. And, at 13 years old, as I watched this video and countless others, I fell in love.

More here.

Roni Dengler in Discover:

In 1984, bacteria started showing up in patients’ blood at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinic. Bacteria do not belong in the blood and such infections can quickly escalate into septic shock, a life threatening condition. Ultimately, blood samples revealed the culprit: A microbe that normally lives in the gut called Enterococcus faecalis had somehow infiltrated the patients’ bloodstreams. Doctors typically treat infections with antibiotics, but these bugs proved resistant to the drugs. The outbreak in the Wisconsin hospital lasted for four years.

In 1984, bacteria started showing up in patients’ blood at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinic. Bacteria do not belong in the blood and such infections can quickly escalate into septic shock, a life threatening condition. Ultimately, blood samples revealed the culprit: A microbe that normally lives in the gut called Enterococcus faecalis had somehow infiltrated the patients’ bloodstreams. Doctors typically treat infections with antibiotics, but these bugs proved resistant to the drugs. The outbreak in the Wisconsin hospital lasted for four years.

Now researchers have finally figured out how this friendly gut bacteria morphed into a vicious pathogen in the blood. The discovery shows not only how the bacteria evolved new ways to survive in an environment entirely different from the gut, but it also shows how E. faecalis skirted both antibiotics and the immune system and sparked the outbreak.

More here.

Ken Roth in The Guardian:

The US government’s indictment of Julian Assange is about far more than a charge of conspiring to hack a Pentagon computer. Many of the acts detailed in the indictment are standard journalistic practices in the digital age. How authorities in the UK respond to the US extradition request will determine how serious a threat this prosecution poses to global media freedom.

The US government’s indictment of Julian Assange is about far more than a charge of conspiring to hack a Pentagon computer. Many of the acts detailed in the indictment are standard journalistic practices in the digital age. How authorities in the UK respond to the US extradition request will determine how serious a threat this prosecution poses to global media freedom.

Journalistic scrutiny is a key democratic safeguard against governmental misconduct. Strong reporting often depends on officials leaking information of public importance. That is why, although many democratic governments prohibit officials themselves from disclosing secret information, few prosecute journalists for publishing leaked information that they receive from officials. Similarly, because electronic communications are so easily traced, today’s investigative journalists often make extraordinary efforts to maintain the confidentiality of their sources, including setting up communication avenues that cannot easily be detected or intercepted.

The Assange prosecution threatens these basic elements of modern journalism and democratic accountability.

More here.

Anne Boyer in The New Yorker:

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

Before I got sick, I’d been making plans for a place for public weeping, hoping to install in major cities a temple where anyone who needed it could get together to cry in good company and with the proper equipment. It would be a precisely imagined architecture of sadness: gargoyles made of night sweat, moldings made of longest minutes, support beams made of I-can’t-go-on-I-must-go-on. When planning the temple, I remembered the existence of people who hate those they call crybabies, and how they might respond with rage to a place full of distraught strangers—a place that exposed suffering as what is shared. It would have been something tremendous to offer those sufferers the exquisite comforts of stately marble troughs in which to collectivize their tears. But I never did this.

Later, when I was sick, I was on a chemotherapy drug with a side effect of endless crying, tears dripping without agency from my eyes no matter what I was feeling or where I was. For months, my body’s sadness disregarded my mind’s attempts to convince me that I was O.K. I cried every minute, whether I was sad or not, my self a mobile, embarrassed monument of tears. I didn’t need to build the temple for weeping, then, having been one. I’ve just always hated it when anyone suffers alone. The surgeon says the greatest risk factor for breast cancer is having breasts. She won’t give me the initial results of the biopsy if I am alone. My friend Cara, who works for an hourly wage and has no time off, drives out to the suburban medical office on her lunch break so that I can get my diagnosis. In the United States, if you aren’t someone’s child or parent or spouse, the law does not guarantee you leave from work to take care of them.

As Cara and I sit in the skylighted beige of the conference room, waiting for the surgeon to arrive, Cara gives me the small knife she carries in her purse so that I can hold on to it under the table. After all these theatrical prerequisites, what the surgeon says is what we already know: I have at least one cancerous tumor, 3.8 centimetres in diameter, in my left breast. I hand the knife back to Cara damp with sweat. She then returns to work.

No one knows you have cancer until you tell them.

More here.

Santiago Zabala in Arcade:

A “call to order” is taking place in political and intellectual life in Europe and abroad. This “rappel à l’ordre” has sounded before, in France after World War I, when it was directed at avant-garde artists, demanding that they put aside their experiments and create reassuring representations for those whose worlds had been torn apart by the war. But now it is directed toward those intellectuals, politicians, and citizens who still cling to the supposedly politically correct culture of postmodernism.

A “call to order” is taking place in political and intellectual life in Europe and abroad. This “rappel à l’ordre” has sounded before, in France after World War I, when it was directed at avant-garde artists, demanding that they put aside their experiments and create reassuring representations for those whose worlds had been torn apart by the war. But now it is directed toward those intellectuals, politicians, and citizens who still cling to the supposedly politically correct culture of postmodernism.

This culture, according to the forces who claim to represent order, has corrupted facts, truth, and information, giving rise to “alternative facts,” “post-truth,” and “fake news” even though, as Stanley Fish points out, “postmodernism sets itself against the notion of facts just lying there discrete and independent, and waiting to be described. Instead it argues that fact is the achievement of argument and debate, not a pre-existing entity by whose measure argument can be assessed.” The point is that postmodernity has become a pretext for the return to order we are witnessing now in the rhetoric of right-wing populist politicians. This order reveals itself everyday as more authoritarian because it holds itself to be in possession of the essence of reality, defining truth for all human beings.

More here.

Kevin Lande in Aeon:

The brain is a computer’ – this claim is as central to our scientific understanding of the mind as it is baffling to anyone who hears it. We are either told that this claim is just a metaphor or that it is in fact a precise, well-understood hypothesis. But it’s neither. We have clear reasons to think that it’s literally true that the brain is a computer, yet we don’t have any clear understanding of what this means. That’s a common story in science. To get the obvious out of the way: your brain is not made up of silicon chips and transistors. It doesn’t have separable components that are analogous to your computer’s hard drive, random-access memory (RAM) and central processing unit (CPU). But none of these things are essential to something’s being a computer. In fact, we don’t know what is essential for the brain to be a computer. Still, it is almost certainly true that it is one.

The brain is a computer’ – this claim is as central to our scientific understanding of the mind as it is baffling to anyone who hears it. We are either told that this claim is just a metaphor or that it is in fact a precise, well-understood hypothesis. But it’s neither. We have clear reasons to think that it’s literally true that the brain is a computer, yet we don’t have any clear understanding of what this means. That’s a common story in science. To get the obvious out of the way: your brain is not made up of silicon chips and transistors. It doesn’t have separable components that are analogous to your computer’s hard drive, random-access memory (RAM) and central processing unit (CPU). But none of these things are essential to something’s being a computer. In fact, we don’t know what is essential for the brain to be a computer. Still, it is almost certainly true that it is one.

I expect that most who have heard the claim ‘the brain is a computer’ assume it is a metaphor. The mind is a computer just as the world is an oyster, love is a battlefield, and this shit is bananas (which has a metaphor inside a metaphor). Typically, metaphors are literally false. The world isn’t – as a matter of hard, humourless, scientific fact – an oyster. We don’t value metaphors because they are true; we value them, roughly, because they provide very suggestive ways of looking at things. Metaphors bring certain things to your attention (bring them ‘to light’), they encourage certain associations (‘trains of thought’), and they can help coordinate and unify people (they are ‘rallying cries’). But it is nearly impossible to ever say in a complete and literally true way what it is that someone is trying to convey with a literally false metaphor. To what, exactly, is the metaphor supposed to turn our attention? What associations is the metaphor supposed to encourage? What are we all agreeing on when we all embrace a metaphor?

More here.

The moon is out. The ice is gone. Patches of white

lounge on the wet meadow. Moonlit darkness at 6 a.m.

Again from the porch these blue mornings I hear an eagle’s cries

like God is out across the bay rubbing two mineral sheets together

slowly, with great pressure.

A single creature’s voice—or just the loudest one.

Others speak with eyes: they watch—

the frogs and beetles, sleepy bats, ones I can’t see.

Their watching is their own stamp on the world.

I cry at odd times—driving, or someone touches my shoulder

or has a nice voice on the phone.

I steel myself for the day.

.

by Nellie Bridge

from EcoTheo Review

July 2018