Clare Bucknell at Literary Review:

The 18th century can seem like a boys’ club at the best of times, so writing a book about an actual all-male club requires delicate handling if it’s to offer something other than the usual narrative. Damrosch’s approach is to show that what makes the Club’s members worth revisiting is the fact that they weren’t always the ‘great men’ we picture them as being. In several cases they were dogged by anxieties or neuroses; often their cultivation of the intellect went hand in hand with an indulgence of powerful physical appetites.

The 18th century can seem like a boys’ club at the best of times, so writing a book about an actual all-male club requires delicate handling if it’s to offer something other than the usual narrative. Damrosch’s approach is to show that what makes the Club’s members worth revisiting is the fact that they weren’t always the ‘great men’ we picture them as being. In several cases they were dogged by anxieties or neuroses; often their cultivation of the intellect went hand in hand with an indulgence of powerful physical appetites.

Johnson suffered from depression (which he called ‘hypochondria’ or ‘indolence’) and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Damrosch also diagnoses, on the basis of rather thin evidence, ‘psychosexual needs’ involving domination and restraint. Boswell’s diarised mood swings indicate bipolar disorder and narcissistic tendencies, and his alcoholism caused memory blanks, self-injury and violent episodes. His fondness for prostitutes (‘I ranged an hour in the street and dallied with ten strumpets’) brought on bouts of venereal disease that would eventually kill him.

more here.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840

Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840  You are what you eat. And when you eat a lot of dirt, the makeup of your gut will change—at least, if you’re a baboon. A new study shows local soils, not genetics, may be the primary determinant of baboons’ gut microbiota, the vast ecosystem of microorganisms that live in the gut, digesting food, fighting infections, and breaking down toxins. Past research has shown that the gut microbiota of baboons varies across different populations. Scientists wanted to know the cause: Is it the genes they share with other relatives, the distance between populations, or the environment that creates these internal changes? To find out, the researchers gathered poop from 14 different baboon populations in Kenya’s primate hybrid zone—an area where yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) and anubis baboons (P. anubis) mingle and interbreed (above). Along with analyzing the baboons’ DNA, researchers looked at 13 different characteristics of the environment where the stool was collected, including vegetation, elevation, climate, and soil.

You are what you eat. And when you eat a lot of dirt, the makeup of your gut will change—at least, if you’re a baboon. A new study shows local soils, not genetics, may be the primary determinant of baboons’ gut microbiota, the vast ecosystem of microorganisms that live in the gut, digesting food, fighting infections, and breaking down toxins. Past research has shown that the gut microbiota of baboons varies across different populations. Scientists wanted to know the cause: Is it the genes they share with other relatives, the distance between populations, or the environment that creates these internal changes? To find out, the researchers gathered poop from 14 different baboon populations in Kenya’s primate hybrid zone—an area where yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) and anubis baboons (P. anubis) mingle and interbreed (above). Along with analyzing the baboons’ DNA, researchers looked at 13 different characteristics of the environment where the stool was collected, including vegetation, elevation, climate, and soil. CAN POEMS TEACH US how to live? What does it mean to approach poetry as a source of self-help? It’s not hard to call to mind examples of poetry that rouse or soothe or refocus a reader, lifting or quieting the mind like a deep breath. Yet much of the poetry encountered in literature classrooms and canonical anthologies may not readily reflect the self that is reading it, and therefore may not readily become a tool of self-improvement. The work of many modernist poets in particular is placed under the banner of “art for art’s sake,” a motto meant to explicitly free such poetry from the responsibility of serving a didactic or utilitarian function. The poems of Wallace Stevens, for instance, are frequently taken to epitomize the kind of high modernist difficulty that in its slippery symbology and ambiguous affect would seemingly resist being reliably employed for any useful purpose.

CAN POEMS TEACH US how to live? What does it mean to approach poetry as a source of self-help? It’s not hard to call to mind examples of poetry that rouse or soothe or refocus a reader, lifting or quieting the mind like a deep breath. Yet much of the poetry encountered in literature classrooms and canonical anthologies may not readily reflect the self that is reading it, and therefore may not readily become a tool of self-improvement. The work of many modernist poets in particular is placed under the banner of “art for art’s sake,” a motto meant to explicitly free such poetry from the responsibility of serving a didactic or utilitarian function. The poems of Wallace Stevens, for instance, are frequently taken to epitomize the kind of high modernist difficulty that in its slippery symbology and ambiguous affect would seemingly resist being reliably employed for any useful purpose. Some people never drink wine; for others, it’s an indispensable part of an enjoyable meal. Whatever your personal feelings might be, wine seems to exhibit a degree of complexity and nuance that can be intimidating to the non-expert. Where does that complexity come from, and how can we best approach wine? To answer these questions, we talk to Matthew Luczy, sommelier and wine director at Mélisse, one of the top fine-dining restaurants in the Los Angeles area. Matthew insisted that we actually drink wine rather than just talking about it, so drink we do. Therefore, in a Mindscape first, I recruited a third party to join us and add her own impressions of the tasting: science writer

Some people never drink wine; for others, it’s an indispensable part of an enjoyable meal. Whatever your personal feelings might be, wine seems to exhibit a degree of complexity and nuance that can be intimidating to the non-expert. Where does that complexity come from, and how can we best approach wine? To answer these questions, we talk to Matthew Luczy, sommelier and wine director at Mélisse, one of the top fine-dining restaurants in the Los Angeles area. Matthew insisted that we actually drink wine rather than just talking about it, so drink we do. Therefore, in a Mindscape first, I recruited a third party to join us and add her own impressions of the tasting: science writer

“

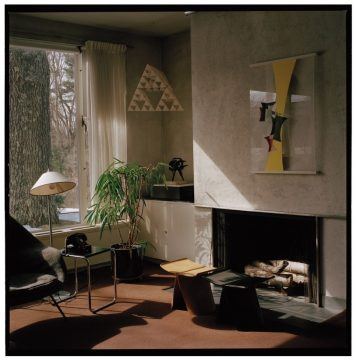

“ Because his genius was untethered to his misery, and because he often handed his ideas off to others, Gropius is a tricky subject for a biographer. Following his lead, we focus on his colorful and eccentric supporting players. As MacCarthy suggests, he had none of the puffery we associate with great architects. He was more a technocrat than a shaman. In a sense, therefore, MacCarthy’s book is a biography of the Bauhaus itself. It’s a story that she presents with a distinctly human-seeming arc. Its childhood unfolded in Weimar, where Itten impressed the students with his mantra, “Play becomes party—party becomes work—work becomes play,” and Gropius read the Christmas story aloud every year. But by early adolescence, in the mid-twenties, the Bauhaus had outstayed its welcome. In 1924, a new provincial government threatened to cut off the school’s subsidies. Nazi factions in the region supposed that all those foreign-looking students were Jews or Jewish sympathizers. The following year, Gropius moved the school to Dessau, an engineering and manufacturing center, southwest of Berlin. There, for the first time, the Bauhaus built itself a campus.

Because his genius was untethered to his misery, and because he often handed his ideas off to others, Gropius is a tricky subject for a biographer. Following his lead, we focus on his colorful and eccentric supporting players. As MacCarthy suggests, he had none of the puffery we associate with great architects. He was more a technocrat than a shaman. In a sense, therefore, MacCarthy’s book is a biography of the Bauhaus itself. It’s a story that she presents with a distinctly human-seeming arc. Its childhood unfolded in Weimar, where Itten impressed the students with his mantra, “Play becomes party—party becomes work—work becomes play,” and Gropius read the Christmas story aloud every year. But by early adolescence, in the mid-twenties, the Bauhaus had outstayed its welcome. In 1924, a new provincial government threatened to cut off the school’s subsidies. Nazi factions in the region supposed that all those foreign-looking students were Jews or Jewish sympathizers. The following year, Gropius moved the school to Dessau, an engineering and manufacturing center, southwest of Berlin. There, for the first time, the Bauhaus built itself a campus. Literature is fire,” Mario Vargas Llosa declared in 1967, when he accepted a prize commemorating Rómulo Gallegos, the esteemed Venezuelan novelist and former president. Gallegos represented the center-left tradition in Latin America, and Vargas Llosa was determined to challenge his audience from the left. Literature, the Peruvian novelist continued, “means nonconformism and rebellion…. Within ten, twenty or fifty years, the hour of social justice will arrive in our countries, as it has in Cuba, and the whole of Latin America will have freed itself from the order that despoils it, from the castes that exploit it, from the forces that now insult and repress it.” Nearly 40 years later, in 2005, Vargas Llosa received a very different sort of prize and delivered a very different kind of speech. Accepting the Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute, he denounced the Cuban government and called Fidel Castro an “authoritarian fossil,” praised the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises as a “great liberal thinker,” and defended calls for privatizing pensions. It was quite a remarkable transformation. In the opening paragraph of Vargas Llosa’s 1969 novel, Conversation in the Cathedral, the protagonist asks: “At what precise moment had Peru fucked itself up?” It is a question that many people have asked as well of Peru’s greatest novelist.

Literature is fire,” Mario Vargas Llosa declared in 1967, when he accepted a prize commemorating Rómulo Gallegos, the esteemed Venezuelan novelist and former president. Gallegos represented the center-left tradition in Latin America, and Vargas Llosa was determined to challenge his audience from the left. Literature, the Peruvian novelist continued, “means nonconformism and rebellion…. Within ten, twenty or fifty years, the hour of social justice will arrive in our countries, as it has in Cuba, and the whole of Latin America will have freed itself from the order that despoils it, from the castes that exploit it, from the forces that now insult and repress it.” Nearly 40 years later, in 2005, Vargas Llosa received a very different sort of prize and delivered a very different kind of speech. Accepting the Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute, he denounced the Cuban government and called Fidel Castro an “authoritarian fossil,” praised the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises as a “great liberal thinker,” and defended calls for privatizing pensions. It was quite a remarkable transformation. In the opening paragraph of Vargas Llosa’s 1969 novel, Conversation in the Cathedral, the protagonist asks: “At what precise moment had Peru fucked itself up?” It is a question that many people have asked as well of Peru’s greatest novelist. IT WAS A

IT WAS A

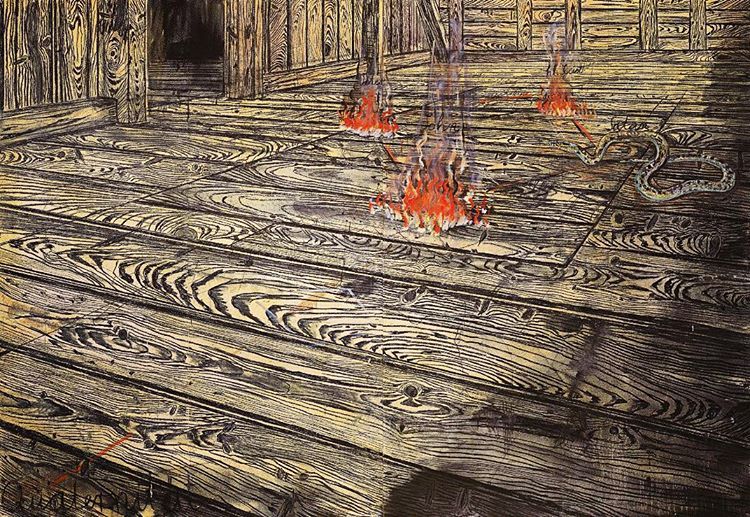

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

Last time

Last time It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1].

It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1].