Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

The Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market is a bland name for a dreadful piece of law likely to reshape our use of the internet. “The transformation of the internet from an open platform for sharing and innovation into a tool for the automated surveillance and control of its users,” was how Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the worldwide web, and 70 other technology pioneers described it in a letter to the president of the European parliament last year. And they’re right.

The Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market is a bland name for a dreadful piece of law likely to reshape our use of the internet. “The transformation of the internet from an open platform for sharing and innovation into a tool for the automated surveillance and control of its users,” was how Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the worldwide web, and 70 other technology pioneers described it in a letter to the president of the European parliament last year. And they’re right.

The two most controversial parts of the new directive are articles 11 and 13 (though, just to complicate matters, in the final law, these have become articles 15 and 17). Article 11, dubbed a “link tax”, obliges search engines and news aggregate platforms to pay for use of snippets from publishers. Article 13 holds platforms, such as Google and YouTube, responsible for material posted without copyright permission and enforces penalties for failure to block infringing content.

Online platforms, the EU argues, make huge profits by either hosting or linking to creative content without funnelling that cash back to the creators. As a writer, I love to be paid for my work and anything to squeeze more money out of every word I write, the better. The trouble is that the EU directive will do little for “content creators” like me. What it will do is constrain my use of the internet.

More here.

We are at an inflection point in the Democratic Party’s history, and in the economic history of the country; similar, perhaps, to the mid-1930s and the late-1970s. In the first period, the country embraced Keynesian, demand-side economics. In the second, during a time of pummeling inflation and wage stagnation, the country turned away from Keynes and toward Milton Friedman and supply-side economics.

We are at an inflection point in the Democratic Party’s history, and in the economic history of the country; similar, perhaps, to the mid-1930s and the late-1970s. In the first period, the country embraced Keynesian, demand-side economics. In the second, during a time of pummeling inflation and wage stagnation, the country turned away from Keynes and toward Milton Friedman and supply-side economics. I had recently been forced to break off a collaboration with another writer over her Russiagate sympathies. Though she was smart and talented, I didn’t feel I could work with someone who considered Russian “interference” in the 2016 election to be a politically significant topic or a major compromise to what passes for American democracy these days. I consider the recent obsession with Russia a sort of liberal hysteria that feeds off of resentment over losing the election to Trump—the nadir of elite entitlement and a pathological state of denial over the fact that their candidate was a dud, and that the electorate rightly holds the Democratic Party in contempt. It’s the bitter delusion of an asshole who lost his girl to a different kind of asshole, and responds with incredulity and conspiratorial rage. What’s more, it’s clearly an attempt to conjure up a totally anachronistic paranoia over the late Soviet Union, a country that hasn’t even existed for nearly thirty years.

I had recently been forced to break off a collaboration with another writer over her Russiagate sympathies. Though she was smart and talented, I didn’t feel I could work with someone who considered Russian “interference” in the 2016 election to be a politically significant topic or a major compromise to what passes for American democracy these days. I consider the recent obsession with Russia a sort of liberal hysteria that feeds off of resentment over losing the election to Trump—the nadir of elite entitlement and a pathological state of denial over the fact that their candidate was a dud, and that the electorate rightly holds the Democratic Party in contempt. It’s the bitter delusion of an asshole who lost his girl to a different kind of asshole, and responds with incredulity and conspiratorial rage. What’s more, it’s clearly an attempt to conjure up a totally anachronistic paranoia over the late Soviet Union, a country that hasn’t even existed for nearly thirty years. Here are some things you can learn from Peattie: sequoias are, of course, the largest of all trees, and the most massive freestanding organisms in the world. They live as long as three thousand five hundred years, longer than all trees but the Chilean alerce and the bristlecone pine, which grows east of here, over the Sierra crest and across the Owens Valley. I like to stand at certain vantage points in the Sierras and imagine that I can look north to the three-thousand-year-old Bennett juniper, west to the sequoias, east to the bristlecones, and south to the ancient clonal stands of Mojavean creosote bush, and be somehow at the center of a circle of inexplicable, primordial genetic wisdom.

Here are some things you can learn from Peattie: sequoias are, of course, the largest of all trees, and the most massive freestanding organisms in the world. They live as long as three thousand five hundred years, longer than all trees but the Chilean alerce and the bristlecone pine, which grows east of here, over the Sierra crest and across the Owens Valley. I like to stand at certain vantage points in the Sierras and imagine that I can look north to the three-thousand-year-old Bennett juniper, west to the sequoias, east to the bristlecones, and south to the ancient clonal stands of Mojavean creosote bush, and be somehow at the center of a circle of inexplicable, primordial genetic wisdom. It’s said the British never stop remarking on their weather. How will they cope in decades to come, when life is all weather, all the time? The country ran a brief test a few weeks ago: in mid- to late February the sun blazed, spring surprised itself, and the temperature in London, where I live, reached over 20°C (68°F). Boon or portent? Meteorological holiday or climate-change hell? Beautiful or sublime? Britons could not agree. It’s now mid-March, and I was awoken at five this morning by rattling windows and the rising shriek of a storm called Gareth (not the direst of names). Abruptly, spring is canceled, and London’s squares are littered with the corpses of premature blossoms.

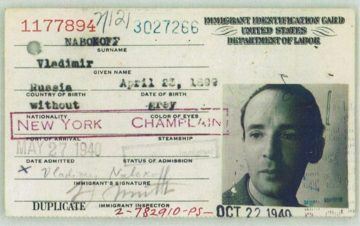

It’s said the British never stop remarking on their weather. How will they cope in decades to come, when life is all weather, all the time? The country ran a brief test a few weeks ago: in mid- to late February the sun blazed, spring surprised itself, and the temperature in London, where I live, reached over 20°C (68°F). Boon or portent? Meteorological holiday or climate-change hell? Beautiful or sublime? Britons could not agree. It’s now mid-March, and I was awoken at five this morning by rattling windows and the rising shriek of a storm called Gareth (not the direst of names). Abruptly, spring is canceled, and London’s squares are littered with the corpses of premature blossoms. Amid frantic, last-minute negotiations, under a spray of machine-gun fire, Vladimir Nabokov fled Russia 100 years ago this week. His family had sought refuge from the Bolsheviks in the Crimean peninsula; those forces now made a vicious descent from the north. The chaos on the pier at Sebastopol could not match the scene that met the last of the Russian imperial family, evacuated the same week: In Yalta, terrified families mobbed a quay littered with abandoned cars. Nor were the Nabokovs’ accommodations as good. The Romanovs made their escape on a British man-of-war. The Nabokovs crowded into a filthy Greek cargo ship. Overrun by refugees, Constantinople turned them away. For several days they lurched about on a rough sea, subsisting on dog biscuits, sleeping on benches. Only the family jewelry traveled comfortably, nestled in a tin of talcum powder. On his 20th birthday, Nabokov disembarked finally in Athens. He would never again set eyes on Russia.

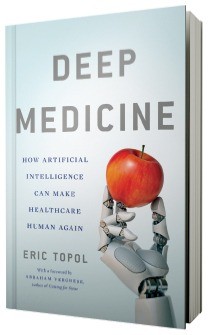

Amid frantic, last-minute negotiations, under a spray of machine-gun fire, Vladimir Nabokov fled Russia 100 years ago this week. His family had sought refuge from the Bolsheviks in the Crimean peninsula; those forces now made a vicious descent from the north. The chaos on the pier at Sebastopol could not match the scene that met the last of the Russian imperial family, evacuated the same week: In Yalta, terrified families mobbed a quay littered with abandoned cars. Nor were the Nabokovs’ accommodations as good. The Romanovs made their escape on a British man-of-war. The Nabokovs crowded into a filthy Greek cargo ship. Overrun by refugees, Constantinople turned them away. For several days they lurched about on a rough sea, subsisting on dog biscuits, sleeping on benches. Only the family jewelry traveled comfortably, nestled in a tin of talcum powder. On his 20th birthday, Nabokov disembarked finally in Athens. He would never again set eyes on Russia. In 1970 in The New England Journal of Medicine, William Schwartz predicted that by the year 2000, much of the intellectual function of medicine could be either taken over or at least substantially augmented by “expert systems”—a branch of artificial intelligence (AI). Schwartz hoped that the medical school curriculum would be “redirected toward the social and psychologic aspects of health care” and that medical schools would attract applicants interested in “behavioral and social sciences and … the information sciences and their application to medicine.” But Schwartz’s dream of smart medical technologies, for the most part, remains just that. Eric Topol, however, is optimistic about the future of health care. In Deep Medicine, he anticipates that new machine learning technologies will improve the precision and accuracy of disease diagnosis, thus providing a better way to identify the best therapies. Like Schwartz, he hopes that the time freed up by these approaches will be devoted to reviving humane medical practices.

In 1970 in The New England Journal of Medicine, William Schwartz predicted that by the year 2000, much of the intellectual function of medicine could be either taken over or at least substantially augmented by “expert systems”—a branch of artificial intelligence (AI). Schwartz hoped that the medical school curriculum would be “redirected toward the social and psychologic aspects of health care” and that medical schools would attract applicants interested in “behavioral and social sciences and … the information sciences and their application to medicine.” But Schwartz’s dream of smart medical technologies, for the most part, remains just that. Eric Topol, however, is optimistic about the future of health care. In Deep Medicine, he anticipates that new machine learning technologies will improve the precision and accuracy of disease diagnosis, thus providing a better way to identify the best therapies. Like Schwartz, he hopes that the time freed up by these approaches will be devoted to reviving humane medical practices.

Insurers have warned that climate change could make coverage for ordinary people unaffordable, after one of the

Insurers have warned that climate change could make coverage for ordinary people unaffordable, after one of the

N

N My first encounter with him is a case in point. It was during the installation of his retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 1981. Ryman sat on top of a large unopened crate, alone in the vast Galeries Contemporaines on the ground floor. Many works were resting against the walls; others were in chariots. Crates and wrapping material were strewn everywhere. After introducing myself I asked him what he was doing. “Waiting,” he said calmly. “Waiting for the electricians to fix the lighting.” Finding out that he had been doing so for a good half hour, I concluded that something was wrong, perhaps lost in translation—surely the electricians’ coffee or cigarette break was not supposed to take that long—and I rushed upstairs to the curatorial office. (At the time, it was located on the third floor.) It turned out that the electricians were waiting elsewhere for Ryman’s call, to be transmitted via the guard in attendance, that he was ready for them to come. They were waiting for his signal that he had determined where the paintings should hang; he was waiting for them to provide absolutely evenly lit walls so that he could start experimenting with the placement of his works.

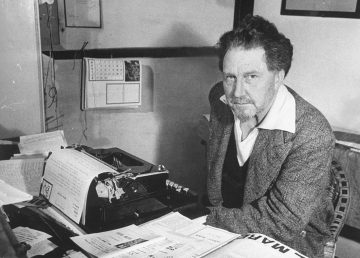

My first encounter with him is a case in point. It was during the installation of his retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 1981. Ryman sat on top of a large unopened crate, alone in the vast Galeries Contemporaines on the ground floor. Many works were resting against the walls; others were in chariots. Crates and wrapping material were strewn everywhere. After introducing myself I asked him what he was doing. “Waiting,” he said calmly. “Waiting for the electricians to fix the lighting.” Finding out that he had been doing so for a good half hour, I concluded that something was wrong, perhaps lost in translation—surely the electricians’ coffee or cigarette break was not supposed to take that long—and I rushed upstairs to the curatorial office. (At the time, it was located on the third floor.) It turned out that the electricians were waiting elsewhere for Ryman’s call, to be transmitted via the guard in attendance, that he was ready for them to come. They were waiting for his signal that he had determined where the paintings should hang; he was waiting for them to provide absolutely evenly lit walls so that he could start experimenting with the placement of his works. Knausgaard has perfected the confessional, ‘speaking’ style of writing that his fellow countryman Knut Hamsun introduced into modern Western literature in the 1890s with novels like Hunger and Mysteries. The style was adopted with great success by Henry Miller, and Miller is probably the confessional novelist with whom Knausgaard can most profitably be compared. Writing in Inside the Whale in 1940 about Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, George Orwell described the experience of feeling that ‘he knows all about me, he wrote this specifically for me’. Orwell praised the healthy and liberating effect of reading Miller during the politically tense 1930s, when it seemed to him that people had begun to censor their own thoughts (‘Ought I to be thinking this?’). Knausgaard’s bold self-acceptance performs a similar function for our own nervous times. His prose is direct. It darts forward. Suddenly he finds himself making a massive assertion. He stops, doubles back on himself, examines the assertion, and either qualifies or reinforces it before moving on. His artistic credo, which he believes he shares with Munch, is senk lista (‘lower the bar’): the important thing is just to keep on writing, in the same way that for Munch all that mattered was to keep on painting. The quality can take care of itself.

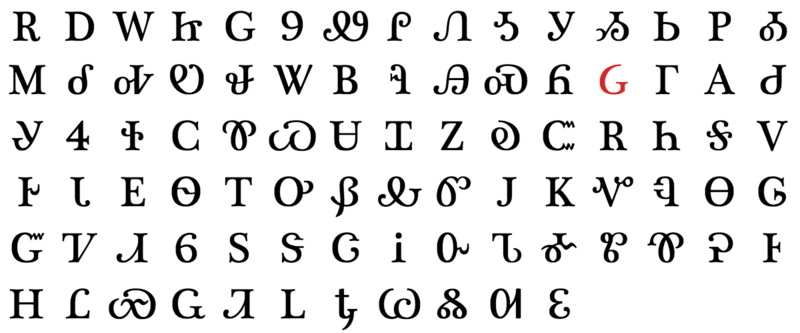

Knausgaard has perfected the confessional, ‘speaking’ style of writing that his fellow countryman Knut Hamsun introduced into modern Western literature in the 1890s with novels like Hunger and Mysteries. The style was adopted with great success by Henry Miller, and Miller is probably the confessional novelist with whom Knausgaard can most profitably be compared. Writing in Inside the Whale in 1940 about Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, George Orwell described the experience of feeling that ‘he knows all about me, he wrote this specifically for me’. Orwell praised the healthy and liberating effect of reading Miller during the politically tense 1930s, when it seemed to him that people had begun to censor their own thoughts (‘Ought I to be thinking this?’). Knausgaard’s bold self-acceptance performs a similar function for our own nervous times. His prose is direct. It darts forward. Suddenly he finds himself making a massive assertion. He stops, doubles back on himself, examines the assertion, and either qualifies or reinforces it before moving on. His artistic credo, which he believes he shares with Munch, is senk lista (‘lower the bar’): the important thing is just to keep on writing, in the same way that for Munch all that mattered was to keep on painting. The quality can take care of itself. At first glance Joan Miró’s painting from 1924, “The Hunter, Catalan Landscape”, looks like a doodle. Imagine it in biro rather than oil paints, and it’s something you might have scribbled during a particularly boring meeting. More than that, it is what people scrawl when they can’t draw: a stick-man, wobbly waves and V-shaped birds, surrounded by blobs, geometric shapes, a bit of lettering. Miró paints these things better than we might, but it remains a doodly mess. But there is method – a story of sorts – in his mess. Miró helpfully drew up an explanatory list of all 58 items in his picture. Gallery blurbs will tell you that they include the hunter (the stick-man), with his rifle (black cone), heading off to cook his rabbit (red-and-yellow whiskered creature), on his grill (squiggly thing with the little flame on the right-hand side). That lettering – sard – at the bottom is for “sardine”, because there’s a sardine skeleton there too, which the hunter has just eaten. And that blob with an eyeball is a carob tree, naturally.

At first glance Joan Miró’s painting from 1924, “The Hunter, Catalan Landscape”, looks like a doodle. Imagine it in biro rather than oil paints, and it’s something you might have scribbled during a particularly boring meeting. More than that, it is what people scrawl when they can’t draw: a stick-man, wobbly waves and V-shaped birds, surrounded by blobs, geometric shapes, a bit of lettering. Miró paints these things better than we might, but it remains a doodly mess. But there is method – a story of sorts – in his mess. Miró helpfully drew up an explanatory list of all 58 items in his picture. Gallery blurbs will tell you that they include the hunter (the stick-man), with his rifle (black cone), heading off to cook his rabbit (red-and-yellow whiskered creature), on his grill (squiggly thing with the little flame on the right-hand side). That lettering – sard – at the bottom is for “sardine”, because there’s a sardine skeleton there too, which the hunter has just eaten. And that blob with an eyeball is a carob tree, naturally. Neuroscientists at The University of Texas at Austin have discovered a group of cells in the brain that are responsible when a frightening memory re-emerges unexpectedly, like Michael Myers in every “Halloween” movie. The finding could lead to new recommendations about when and how often certain therapies are deployed for the treatment of anxiety, phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the new paper, out today in the journal Nature Neuroscience, researchers describe identifying “extinction neurons,” which suppress fearful memories when they are activated or allow fearful memories to return when they are not. Since the time of Pavlov and his dogs, scientists have known that memories we thought we had put behind us can pop up at inconvenient times, triggering what is known as spontaneous recovery, a form of relapse. What they didn’t know was why it happened. “There is frequently a relapse of the original fear, but we knew very little about the mechanisms,” said Michael Drew, associate professor of neuroscience and the senior author of the study. “These kinds of studies can help us understand the potential cause of disorders, like anxiety and PTSD, and they can also help us understand potential treatments.”

Neuroscientists at The University of Texas at Austin have discovered a group of cells in the brain that are responsible when a frightening memory re-emerges unexpectedly, like Michael Myers in every “Halloween” movie. The finding could lead to new recommendations about when and how often certain therapies are deployed for the treatment of anxiety, phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the new paper, out today in the journal Nature Neuroscience, researchers describe identifying “extinction neurons,” which suppress fearful memories when they are activated or allow fearful memories to return when they are not. Since the time of Pavlov and his dogs, scientists have known that memories we thought we had put behind us can pop up at inconvenient times, triggering what is known as spontaneous recovery, a form of relapse. What they didn’t know was why it happened. “There is frequently a relapse of the original fear, but we knew very little about the mechanisms,” said Michael Drew, associate professor of neuroscience and the senior author of the study. “These kinds of studies can help us understand the potential cause of disorders, like anxiety and PTSD, and they can also help us understand potential treatments.”