by Leanne Ogasawara

Anyone who has ever found themselves caught in a staring contest with an octopus –those soulful cat-eyes returning your gaze through the thick glass of an aquarium tank– can attest to the uncanny power these creatures exert over our human imagination.

They certainly look alien. With three hearts pumping blue, copper-infused blood, their tentacles (“each with a mind of its own”) are covered in suckers that can feel AND taste. Because their beaks are the only hard parts of their bodies, a large octopus can squeeze through a hole not much bigger than one of their eyeballs. They are like the Great Houdinis of the deep! Without a hard shell like other mollusks, octopuses have evolved clever ways for keeping a step ahead of predators: Not only can they change colors to camouflage themselves, blending into almost any watery environment, but they can also send out ink bombs. After lobbing one to confuse an enemy, an octopus can jet propel away from danger at surprising speeds in a funnel of water.

Is it any wonder that there have been people who believe they might have originated in space? From the Scandinavian myth of the Kraken and Jules Vernes’ 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, to Japanese sea monsters and the sexual predators found in erotic shunga prints, again and again–in so many cultures around the world– these creatures show up in stories and art as monsters and space aliens. And who could forget the fear instilled in the losing soccer teams by Paul the Clairvoyant World Cup Octopus? The Argentines got so angry at him that they threatened to kill him and cook him in a paella, if he kept foretelling their bad luck!

My own personal octopus “horror” is the not-as-rare-as–you-would-think sight of Japanese TV personalities (and a few of my friends) traveling in Korea and eating live octopuses–desperate tentacles clawing their way out of the people’s mouths!

2. Is consciousness a function of intelligence? Are more intelligent creatures more conscious?

2. Is consciousness a function of intelligence? Are more intelligent creatures more conscious?

Peter Godfrey-Smith, in his book Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, points out just how far back in time human beings and octopuses diverged from each other on the evolutionary tree of life. As fellow primates, human beings shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees as recently as six million years ago. Chimpanzees are our living cousins. But compared to octopuses, so are cats. While not as close to us as our mammalian brethren, we know that parrots, magpies, and crows (also vertebrates) are highly intelligent. But to find our common ancestor with birds, you would have to go back more than fifty times further than to that of chimpanzees– all the way back to a lizard-like creature who lived around 320 million years ago.

Guess how far back you have to go to find a common ancestor with an octopus?

You have to go very far back indeed, to a worm-like creature that scuttled on the ocean’s floor around 600 million years ago. And to keep this in perspective, recall that dinosaurs only arrived on the scene around 230 million years ago. This is all to say that we are very distantly related to octopuses. And this fact alone could go far in explaining what we find so unsettling about the octopus gaze.

Sy Montgomery, in her Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration Into the Wonder of Consciousness, says it like this about octopus intelligence:

We split from our common ancestor with the octopus half a billion years ago. And yet, you can make friends with an octopus.

3. Can a computer be conscious? How about a network of trees?

3. Can a computer be conscious? How about a network of trees?

Octopuses have existed over a thousand times longer than humans. They have neuron numbers comparable to those of some mammals, but their “brains” are distributed throughout their bodies. Their tentacles, for example, have nearly twice as many neurons as their central brain. These tentacles appear to be autonomous, having neural loops that may even give the tentacles their own form of memory. Wonderful to imagine that an octopus can “see” light with their skin. To try and get at just how differently evolved they are from us, Peter Godfrey-Smith goes to great care in explaining the way an octopus body is so suffused with its nervous system that it has no clear brain-body boundary.

This is a crucial point of entry into the question of consciousness.

Last month, I wrote about Descartes and the tradition of mind-body duality that has been passed down in the European philosophical tradition. Considering current on-going research into brain science and consciousness, I mentioned recent books by Caltech’s Christof Koch and Douglas Hoftstadter of Godel, Escher and Bach fame. It was interesting for me to discover that the hard-core reductionist mentioned in that post (books below) are aligned with the two octopus-watchers mentioned above in their vehement rejection of Cartesian dualism. Indeed, we find ourselves, at long last, moving beyond the traditional European notion of a non-corporeal mind encapsulated inside the shell of our physical bodies. It is important to note that in this traditional understanding, it is only human beings which are granted consciousness. Koch, who was raised in the Roman Catholic faith, movingly describes how his own scientific journey in the field of consciousness studies began with his vehement rejection of the church’s insistence that dogs don’t go to heaven. And this was religious notion was carried into science and informs much of our industrial animal and agricultural practices. Indeed, you will cringe to learn that until quite recently, scientists were performing amputations on octopus limbs without any pain relief, because they did not recognize that animals feel pain as we do.

Rejecting this kind of Western dualism, the scientists and philosophers mentioned above see consciousness as existing in degrees –on a spectrum–from lower to higher forms. “Souls of different sizes,” in Hofstadter’s language. Hofstadter even has a name for this degree, calling it “a Huneker” after the music critic James Huneker who wrote an essay that captured the attention of the young Douglas Hofstadter about Chopin’s eleventh etude Opus 25. In the essay, Huneker cautioned fellow pianists that: “Small-souled men, no matter how agile their fingers, should not attempt it.” Hofstadter knows it is dangerous to entertain the idea of small and large souled men in today’s world. But he does see consciousness as existing in all kinds of organisms on a sliding scale (See Note below).

4. Can consciousness be shared? Can it be uploaded? Downloaded? Can it exist on wildly different timescales; for example, very slowly in trees?

4. Can consciousness be shared? Can it be uploaded? Downloaded? Can it exist on wildly different timescales; for example, very slowly in trees?

Peter Wohllenben, the author of the Hidden Life of Trees, began his career in forestry; where he says, “I knew as much about trees as a butcher knows about animals.” Trees were resources to be efficiently managed, eventually turned into commodities. It was only much later on in his career, when he began leading nature walks into the forest, that he began to see trees in a very different light. And what he found (all backed up by recent science) is that not only are trees a crucial part of the network of life (which I think we already know), but that they are social. What does he mean by this? Well, he found them to be capable of sharing resources. And more, that they “consciously” band together to do so. While having different projects from human beings, he tells us that trees feel pain and also learn –and possibly even communicate. Calling this communication network the “woodwide web,” Wohllenben paints a picture of trees communicating using electrical signals via their roots and across fungi networks (“like our nervous system”) to other trees nearby. Wohllenberg is not arguing that trees as individuals have minds, but rather that that the ecosystem itself does. Donna Haraway, in her book, Staying with the Trouble, also focuses on paradigms that look at interconnectedness and ecosystems. How are we co-evolving and what are the kinships that exist between the three kingdoms? “Every species is a multispecies crowd,” she says.

When asked whether he feels trees have souls, Christof Koch likewise responded that in the same way that individual neurons don’t have consciousness, it is the forest ecosystem that we need to look at when we study question of consciousness in trees. Maybe someday complex computer networks like the world wide web could likewise develop consciousness–like the trees in the forest. We already even have a word for this phenomenon: “hive mind.” Bees display this–but so do ants. There is a wonderful article in Nautilus about Stanford entomologist Deborah Gordon’s recent book Ants at Work, called “Ants Swarm Like Brains Think,” which makes a similar point, that the problem of consciousness should be approached in terms of networks, which are themselves embedded in local ecosystems.

From soil to plants to animals: we must acknowledge that we ourselves are embedded in this ecosystem–not set apart from it.

5. Our future depends on our ability to be able to expand our consciousness and reconnect with the rich web of life into which we were born.

5. Our future depends on our ability to be able to expand our consciousness and reconnect with the rich web of life into which we were born.

When did our lives become so isolated? Hunkered down in nuclear family units and plugged into what seems like some pretty heavy-duty echo chambers, sometimes it doesn’t seem that we are very capable of listening to each other anymore–-much less listening to the world of non-human animals, plants and trees around us.

In what was the most unusual book I read last year, Mushroom at the End of the World, anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing begins her long meditation on late-capitalist commodity chains and devastated landscapes by looking at the way Enlightenment philosophy was itself built on this concept of mind-body duality, coming to view nature (lacking in mind and soul) as being set apart from human beings. While nature may be grand and universal, it is also passive and mechanical, she says. Nature is seen as more of a backdrop and resource. Something to be used; for which “the moral intentionality of man could tame and master.” Her book is interesting as it avoids the use of the word “Anthropocene,” instead describing our current paradigm as one of “post-capitalist ruin.” This is crucial, for according to Lowenhaupt Tsing , the history of the human accumulation of wealth has turned not just the environment, but human beings as well, into resources and this has led to the state of deep alienation we find ourselves in. From economic theories of self-interest to scientific theories of the “selfish gene,” we have come to view ourselves as being isolated. And it is in this lack of understanding of interconnectedness that is leading to our ruin.

6. Time for a new understanding of being

6. Time for a new understanding of being

As early as the 1950s, German philosopher Martin Heidegger in his book The Question Concerning Technology explored the way in which technological ways of seeing (not the technologies themselves) poison our imagination in turning everything around us into resources to be efficiently managed and utilized. Like all of the thinkers mentioned in this essay, Heidegger was asking how we can relate ourselves to the world in a way that not only resists its devastation but generates positive new relationships. How can we make peace with the non-human world in the face of possible climate disaster? Scientists do not understand what consciousness is, or where it is located, and one could argue it is in fact not located anywhere and is instead a product of a complex web of connections, and has diverse forms working over vast scales of complexity, time and space. We share it with animals that are similar to us, and with beings that seem completely foreign (octopuses, cockroaches, trees), i.e. we all share this nature. Humanity is becoming more and more estranged from its natural roots and context, removing ourselves from and destroying these complex webs of interdependency and connection in the service of utility and efficiency and the predominance of the individual ego.

Co-evolution implies the necessity of co-existence. And we must move beyond treating everything in the world (including our own selves) as resources for efficient utilization. A first step will be to uncover the latent commons around us—to learn to speak the language of nature before it is too late. So, maybe when we find ourselves locked in a staring contest with an octopus, we believe we are seeing our own conscious minds mirrored in the eyes of the octopus. That this looking eye is pointing back to our own hearts. But this not a very healthy way of looking, is it? Wouldn’t it be better to see reflected the entire ocean of being there within the eyes of the octopus? This kind of “seeing” probably has more in common with listening. What is nature saying to us? Just because we don’t speak its language doesn’t mean we stand apart from it. And indeed, it is seeming more and more like our future depends on our ability to be able to reconnect and be in communion with each and with the rest of all nature. We don’t listen at our own peril.

++

Note: Consciousness is usually loosely defined as the inner, qualitative, subjective, and processes associated with states of sentience or awareness. It is something that diminishes or even disappears when we sleep, for example. For a different understand, I recommend Evan Thompson’s ‘Waking, Dreaming, Being. Thompson looks at consciousness through the lens of Indian and Tibetan contemplative traditions, where consciousness is present even during deep sleep. I also recommend this TED talk by Christof Koch on animal soul/minds, the scientific pursuit of consciousness and the imperative of reducing suffering in all creatures

For Jim (original title was on the path toward vegetarianism)

++

Art

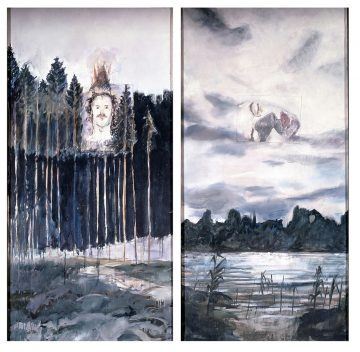

Anselm Kiefer (1971) Kopf im Wald (Thanks Brooks!!)

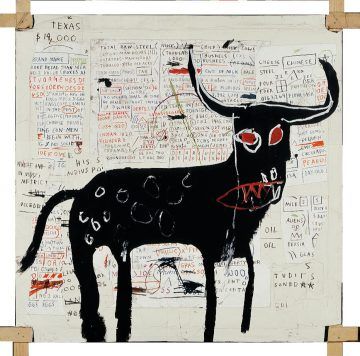

Jean‐Michel Basquiat (1982) Beef Ribs Longhorn & Eyes and Eggs (1983)

Further Reading

++

Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness

Sy Montgomery’s Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness

Christof Koch’s Consciousness: Conversations of a Romantic Reductionist

Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid? & I Am A Strange Loop

Peter Wohllenben’s The Hidden Life of Trees

Deborah Gordon’s Ants at Work

Lierre Keith’s The Vegetarian Myth: Food, Justice, and Sustainability

Union of Concerned Scientist’s Cooler Smarter: Practical Steps for Low-Carbon Living

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s Mushroom at the End of the World

Timothy Morten’s Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

Martin Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology

Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

Michael Pollen’s How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence

++

Also recommend Sean Carroll’s podcast with David Chalmers (who is working on a new book on the subject) on Consciousness, the Hard Problem, and Living in a Simulation

And Paul Stamets (who has a new book coming out called Fantastic Fungi) video Fantastic Fungi

New Atlantis/Understanding Heidegger on Technology

New Atlantis: Do Elephants Have Souls?

Documentary Film: Soil! The Movie