by Thomas Manuel

“The last time there was a protest in this country, they didn’t just arrest everyone – they killed the protestors and carried on killing for weeks after. Ever since then, people here have been very afraid.” “When was this?” I asked. “Nineteen seventy-seven,” he said, “and they killed thousands.” – Lara Pawson, The 27 May in Angola: a view from below

It’s simultaneously sotto voce and hyper-visible. – Marissa Moorman, The battle over the 27th of May in Angola

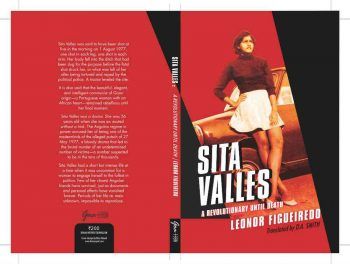

“Sita Maria Dias Valles …remains, for all intents and purposes, missing. Her body was never returned to her family. She was about to turn 26 when she was executed.” – Leonor Figueiredo, Sita Valles: A Revolutionary Until Death

If stories have shapes, this one lies over the sphere of the Earth like a triangle. The three vertices or points of this triangle lie on three different continents: one in India, one in Angola and one in Portugal. But the lines that join these points, that form these vertices, traverse not just space but time.

Goa, India

In the 16th century, Afonso de Albquerque attacks Goa and captures it from the Muslim king who ruled it. Goa becomes the capital of the Portuguese maritime operations in Asia. Through this tiny land, the riches and rarities of South East Asia traveled to Europe. It remained like this for four and a half centuries.

In 1947, the country of India gained its independence and threw off the grasping hands of the British Empire but the Portuguese held on to Goa with a deathly grip. The Salazar regime did not hesitate to shoot and kill Goans who agitated for independence.

In 1961, the Indian army marched into Goa and claimed the land. (In the process, they destroyed a Portuguese frigate named after Afonso de Albquerque. That is the nature of history.) The US and the UK would try to condemn the invasion in the United Nations but the then USSR would veto it.

Portugal

In 1933, Salazar forms the Estada Novo or New State, an authoritarian regime that he would preside over as dictator till 1968 when illness forced him to step aside.

In 1971, Sita Valles transferred to Lisbon to continue her medical education at a medical university there. She joined the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP). As a member of the PCP, Sita was tremendously active, often described as reckless, risking not only her life but those around her. She abandoned her studies and dived into politics. Through the PCP, she visited Moscow as a delegate and came back inspired. Her family, on the other hand, was heartbroken by this turn.

In Figuiredo’s book, Sita Valles: A Revolutionary Until Death, recently translated into English by D.A. Smith and published by Goa 1556, we get to see Sita at this time through her senior, Zita Seabra. Seabra says, “She was a romantic, an adventurer, a revolutionary… She liked to dress well. She was joyful and decisive, and completely unattached to material things. She would offer you the shirt off her back.”

In 1974, the Carnation revolution, a leftist coup, swept aside the Estada Novo and formed a democratic government.

In early 1975, Sita left for Angola. Zita Seabra says, “She went at the moment when the PCP thought that the revolution was won… Sita considered herself Angolan; she never lost those roots, her identity. She talked about Angola as her homeland, and felt an obligation to go. She made the decision and was unyielding about it.” At the same time, as Angola headed towards independence, her parents along with thousands of others were moving (returning, in many cases) to Portugal, driven by fear of what would come.

Angola

In the 15th century, much before they would arrive in India, the Portuguese arrived in what is now Angola. For centuries, they grew fat off the slave trade. Then, they conquered the entire territory and finally in the 19th century, abolished slavery.

In 1943, Edgar Francisco Valles, a Goan migrated from India to the Portuguese territory of Angola to work as an agricultural engineer. Maria Lucia Dias, another Goan from a “good family”, married him a few years later and they had three children: Ademar, Sita Maria and Edgar.

In her book, Figueiredo quotes Edgar Francisco’s daughter-in-law describing him thus: “He jotted everything down, from diarrhea to measles, even his children’s successes and failures in school. He was shockingly intelligent; he spoke five languages. He thought that all the sciences should have mathematics as their base. He made lengthy quotations in Latin. His worth was never recognized. He was private, serious. Once, he asked a colleague to look over the technical book he’d written and write a preface. The colleague published it as if it were his own. Do you know what he said? That what mattered was that the book’s content had been published. He was an outsider.”

In 1968, Sita Valles joined medical school in Luanda. There, through critiques of the healthcare system and colonialism, she discovered an environment humming with vibrant student politics. Since 1961, there had been a protracted war for independence being fought with multiple factions representing the Angolan people. These freedom struggles had their roots in labour movements as under colonial law, black Angolans couldn’t unionize.

In 1975, Sita returned to Angola and began to work with Nito Alves, one of the leaders of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). Alves was a battle commander and a poet, had risen through the ranks and was now one of the organization’s senior leaders. In June, the MPLA fought a battle for the control of Luanda, the capital, and won. Sita met and fell in love with José Van-Dúnem, one of Nito Alves’ lieutenants, and they would soon have a son together named Che. All three of them – Nito Alves, José Van-Dúnem and Sita Valles – would be killed within the next two years.

On 11th November 1975, the MPLA declared independence and formed a government under its leader, Agostinho Neto.

In March 1976, Lucio Lara, the second-in-command at the MPLA, expelled Sita Valles from one of the MPLA’s committees as a part of a move to eradicate all those who had ties to other political organizations. In Sita’s case, this was the Portuguese Communist Party. Her fondness for Moscow also did her no favours, it seems. Lara also seemed to personally dislike Sita who had criticized the MPLA’s leaders appropriating large colonial houses as their residences and she was described as a foreigner often.

Defiantly, she continued being active and increasingly ominous messages were passed to her, some of them well-intentioned. She was told that neither the PCP nor the USSR supported her actions. But she continued her political work on top of the long hours spent in the terrible hospitals and ailing medical infrastructure that Angola had inherited from its colonial oppressors. In a letter to her parents, Sita would describe her job at the pediatrics department as seeing “a lot of death, a huge lack of doctors and staff, a lot of illness.”

In May 1977, at an MPLA congress, Nito Alves and Van-Dúnem were thrown out of the party as well. Agostinho Neto began to speak of fraccionistas and fraccionismo, those who were secretly working for the imperialist cause and trying to undermine the revolutionary project.

After his expulsion, Nito Alves became the opposition. He was popular with the people and had the support of the 9th Brigade of the army. From here, the story gets murky. Nito Alves might’ve planned a coup with the promised support of the USSR or it might’ve just been a demonstration. He might’ve planned to kidnap Neto or a hundred other things. There is no consensus on what the plan actually was for the 27th of May but it failed and the MPLA struck back over with unforeseen levels of brutality. In this brutality, they were aided at every turn by the Cuban army sent by Castro.

Nito Alves was probably captured early on and executed by firing squad. Sita and Van-Dunem were captured a few months later, hiding in a village. They were initially imprisoned and despite numerous passionate pleas from her parents in Portugal, it is believed that they were later shot and dumped in unmarked graves.

The number of people that died in the aftermath of that coup vary. Some say 12,000. Some say 80,000. Regardless, the pools of blood were legion and generations would swim in them. It was a ferocious massacre – where a last name or a favourite football club would have been enough of a death sentence, as was the case of Ademar, Sita’s brother, and the followers of the Sambizanga football team of which Nito Alves was the President.

In an interview, journalist Lara Pawson said, “One historian has said that 27 May 1977 is the day freedom died in Angola. I certainly think it’s the day that the idea of freedom died.”