by Adele A Wilby

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

Wohlleben draws on his twenty years as a government forester, and then manager of his own environmentally friendly forest in Germany, and his scientific knowledge, to share with us his experience of the inter-related, yet complex lives of a myriad of life forms in the plant and animal worlds. The result is a joy to read.

Each of his books can be read, and appreciated, in their own right, but collectively they amount to what is, in effect, how Wohlleben relates to and the respect he has for all life forms that constitute nature. The trilogy is successful, in my view, for the way he makes accessible to us his experience of working with nature, moderated by a judicious use of biological jargon. However, it is also his use of personification in his exposition of his subjects that makes it possible for the reader to realise just how integrated are the lives of all living creatures. The books are for people like me who do not have the time to take up the environment and the biological sciences as new disciplines to study, but are nonetheless interested in the natural world amidst which we live. In reading these texts we are provided with sufficient knowledge to deepen our understanding and appreciation of the natural world, and to wet our appetite to learn more about the subjects. Read more »

WHAT SECRETS DO THE EAR BONES

WHAT SECRETS DO THE EAR BONES Every wild species on the planet knows to eat the diet to which it is adapted. Carnivores know to eat meat; herbivores know to eat leaves and grass; koalas know to eat eucalyptus, and giant pandas know to eat bamboo. We, too, are animals; we too, once knew what to eat based on that same blend of cultural experience and instinct. Science should only have served to enhance our native understanding. Instead, we have so abused the applications of science to nutrition that while pandas keep eating bamboo, humans are being bamboozled.

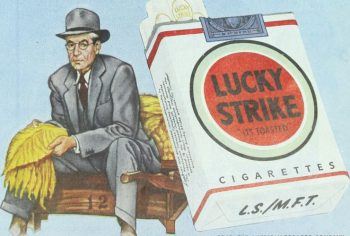

Every wild species on the planet knows to eat the diet to which it is adapted. Carnivores know to eat meat; herbivores know to eat leaves and grass; koalas know to eat eucalyptus, and giant pandas know to eat bamboo. We, too, are animals; we too, once knew what to eat based on that same blend of cultural experience and instinct. Science should only have served to enhance our native understanding. Instead, we have so abused the applications of science to nutrition that while pandas keep eating bamboo, humans are being bamboozled. Capitalism, like the United States itself, has a mythology, and for five decades one of its central characters has been the nineteenth-century maverick cigarette entrepreneur, James B. Duke. Duke’s risk-taking investment in the newfangled machine-made cigarette, so the story goes, displaced the pricey, hand-rolled variety offered by his stodgy competitors. This, in turn, won Duke control of the national, and soon global, cigarette market. Repeated ad nauseam in

Capitalism, like the United States itself, has a mythology, and for five decades one of its central characters has been the nineteenth-century maverick cigarette entrepreneur, James B. Duke. Duke’s risk-taking investment in the newfangled machine-made cigarette, so the story goes, displaced the pricey, hand-rolled variety offered by his stodgy competitors. This, in turn, won Duke control of the national, and soon global, cigarette market. Repeated ad nauseam in  As I looked around, Julia said, “People are always surprised my kitchen is not more high tech.” Actually, I had imagined it would resemble one of the glamorous sets on The French Chef. My first thought was, “Where is the island? Julia Child always works at an island.” I admit now to being a little disappointed. I had been fooled by the illusion of TV. What I saw instead was a smallish, old-fashioned, eat-in kitchen with cluttered countertops and cabinets seriously in need of painting. By then it was nearly 30 years old—and it looked its age. Yet, the more I looked around, the more I realized that it was a fascinating and important place, with its old stove and its batterie de cuisine, with what looked like thousands of glistening cooking implements close at hand. It was a very comfortable and welcoming workroom full of carefully chosen tools and fixtures. Here are some of the most important things I noticed that day.

As I looked around, Julia said, “People are always surprised my kitchen is not more high tech.” Actually, I had imagined it would resemble one of the glamorous sets on The French Chef. My first thought was, “Where is the island? Julia Child always works at an island.” I admit now to being a little disappointed. I had been fooled by the illusion of TV. What I saw instead was a smallish, old-fashioned, eat-in kitchen with cluttered countertops and cabinets seriously in need of painting. By then it was nearly 30 years old—and it looked its age. Yet, the more I looked around, the more I realized that it was a fascinating and important place, with its old stove and its batterie de cuisine, with what looked like thousands of glistening cooking implements close at hand. It was a very comfortable and welcoming workroom full of carefully chosen tools and fixtures. Here are some of the most important things I noticed that day. Last April, I decided to set up a satirical account on Twitter under the guise of radical intersectionalist poet

Last April, I decided to set up a satirical account on Twitter under the guise of radical intersectionalist poet  Most Americans still cling to the meritocratic notion that people are rewarded according to their efforts and abilities. But meritocracy is becoming a cruel joke.

Most Americans still cling to the meritocratic notion that people are rewarded according to their efforts and abilities. But meritocracy is becoming a cruel joke. I suppose it’s true that “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” as the Washington Post’s slogan says. But journalism may also die, by morphing into forms that can no longer be described as journalism. Journalism may come to mean a crooked scandal sheet, or high-minded propaganda. Sometimes squalor and self-righteousness are equally disreputable. The Post’s apothegm, somehow off-kilter, with its alliteration and self-importance, was a purposeful bit of branding, designed to claim high ground and to poke a thumb in President Trump’s eye every morning. Such partisan intent detracts from the slogan’s claim to universality. The self-serving implication—the notion that, against the Darkness, the Washington Postrepresents the Light—invites the reader to respond (as readers have always responded to the Chicago Tribune’s slogan, “The World’s Greatest Newspaper”) by muttering, “I’ll be the judge of that, pal.”

I suppose it’s true that “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” as the Washington Post’s slogan says. But journalism may also die, by morphing into forms that can no longer be described as journalism. Journalism may come to mean a crooked scandal sheet, or high-minded propaganda. Sometimes squalor and self-righteousness are equally disreputable. The Post’s apothegm, somehow off-kilter, with its alliteration and self-importance, was a purposeful bit of branding, designed to claim high ground and to poke a thumb in President Trump’s eye every morning. Such partisan intent detracts from the slogan’s claim to universality. The self-serving implication—the notion that, against the Darkness, the Washington Postrepresents the Light—invites the reader to respond (as readers have always responded to the Chicago Tribune’s slogan, “The World’s Greatest Newspaper”) by muttering, “I’ll be the judge of that, pal.”

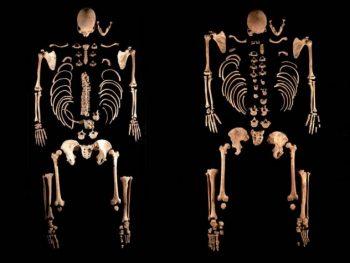

Who were the Neanderthals? Even for archaeologists working at the trowel’s edge of contemporary science, it can be hard to see Neanderthals as anything more than intriguing abstractions, mixed up with the likes of mammoths, woolly rhinos and sabre-toothed cats. But they were certainly here: squinting against sunrises, sucking lungfuls of air, leaving footprints behind in the mud, sand and snow. Crouching to dig in a cave or rock-shelter, I’ve often wondered what it would be like to watch history rewind, and see the empty spaces leap with shifting, living shadows: to collapse time, reach out, and allow my skin to graze the warmth of a Neanderthal body, squatting right there beside me.

Who were the Neanderthals? Even for archaeologists working at the trowel’s edge of contemporary science, it can be hard to see Neanderthals as anything more than intriguing abstractions, mixed up with the likes of mammoths, woolly rhinos and sabre-toothed cats. But they were certainly here: squinting against sunrises, sucking lungfuls of air, leaving footprints behind in the mud, sand and snow. Crouching to dig in a cave or rock-shelter, I’ve often wondered what it would be like to watch history rewind, and see the empty spaces leap with shifting, living shadows: to collapse time, reach out, and allow my skin to graze the warmth of a Neanderthal body, squatting right there beside me. Our system—as evidenced by studies at

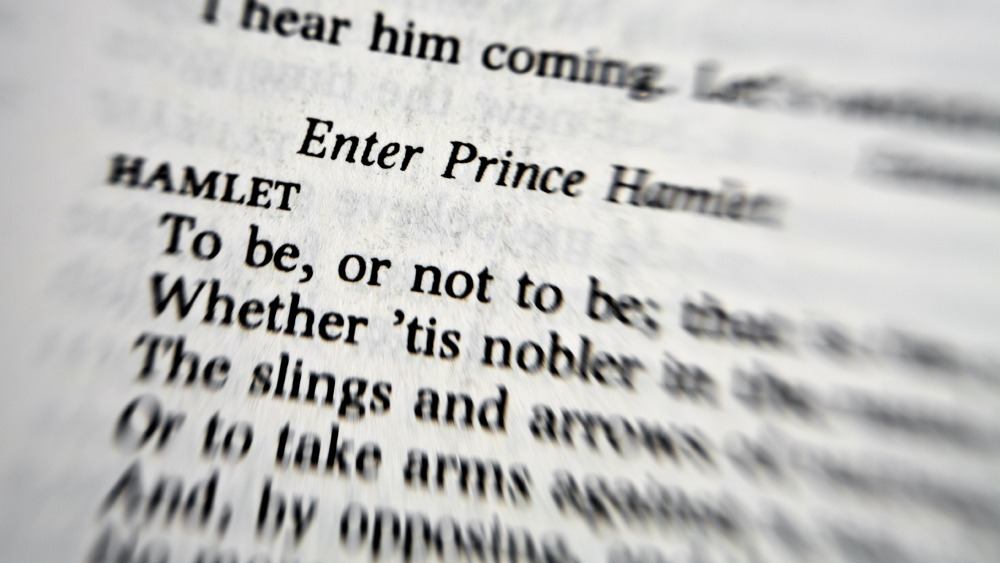

Our system—as evidenced by studies at  An essential fact about the Hebrew Bible is that most of its narrative prose as well as its poetry manifests a high order of sophisticated literary fashioning. This means that any translation that does not attempt to convey at least something of the stylistic brilliance of the original is a betrayal of it, and such has been the case of all the English versions done by committee in the modern period.

An essential fact about the Hebrew Bible is that most of its narrative prose as well as its poetry manifests a high order of sophisticated literary fashioning. This means that any translation that does not attempt to convey at least something of the stylistic brilliance of the original is a betrayal of it, and such has been the case of all the English versions done by committee in the modern period. This “the ideology of cure” also focuses on the future of the disabled individual rather than on their present. Clare points out how various forms of activism often promote cure as the only response to body-mind difference and loss. For example, charity walks and runs exclude disabled individuals from participation and focus on the fear of becoming different or acquiring disability through a disease like cancer or cerebral palsy, rather than strive toward health and longevity of life for those that are suffering.

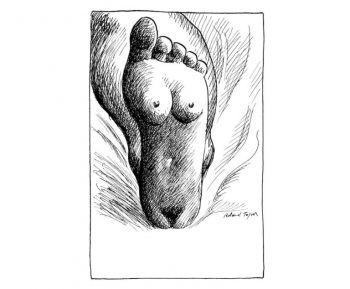

This “the ideology of cure” also focuses on the future of the disabled individual rather than on their present. Clare points out how various forms of activism often promote cure as the only response to body-mind difference and loss. For example, charity walks and runs exclude disabled individuals from participation and focus on the fear of becoming different or acquiring disability through a disease like cancer or cerebral palsy, rather than strive toward health and longevity of life for those that are suffering. While he is best known in his native France as an artist, and perhaps for his turn as Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979), Roland Topor’s written works are still generally unacknowledged. In the scant body of critical writing surrounding his books, they are classed as “post-surrealist horror” that demonstrate “the same half-sane magnifications that strike home in Kafka.” And yet to read his novels, short stories, and plays is to enter a world far from the sleek poeticisms of Breton’s Nadja (1928) or indeed the safety of a barricaded room in which Gregor Samsa hides his transformation in The Metamorphosis (1915). Topor’s writing, much like his illustrations, plunges the reader again and again into predicaments in which grotesque metamorphoses are encountered already in advanced states of development and resultant crisis. In this way, the narratives lead us in a sense to the ground where Breton and Kafka leave off.

While he is best known in his native France as an artist, and perhaps for his turn as Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979), Roland Topor’s written works are still generally unacknowledged. In the scant body of critical writing surrounding his books, they are classed as “post-surrealist horror” that demonstrate “the same half-sane magnifications that strike home in Kafka.” And yet to read his novels, short stories, and plays is to enter a world far from the sleek poeticisms of Breton’s Nadja (1928) or indeed the safety of a barricaded room in which Gregor Samsa hides his transformation in The Metamorphosis (1915). Topor’s writing, much like his illustrations, plunges the reader again and again into predicaments in which grotesque metamorphoses are encountered already in advanced states of development and resultant crisis. In this way, the narratives lead us in a sense to the ground where Breton and Kafka leave off.