Samantha Weinberg in More Intelligent Life:

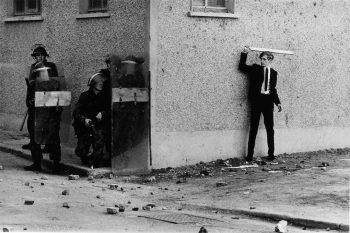

The horrors of the battlefield are never far away in Tate Britain’s retrospective of Don McCullin’s work: the dead Khmer Rouge soldiers in a crater in Cambodia, Congolese soldiers tormenting freedom fighters in Stanleyville, young Christians on a bombed-out Beirut street, posing like a boy band over the body of a dead Palestinian girl. But McCullin has said again and again that he doesn’t like to be called a war photographer; preferring, simply, “photographer”. He is as interested in the people fighting wars as the people caught in their rip tide. “Starving Twenty Four Year Old Mother With Child” taken in Biafra in 1968, shows a woman, so gaunt she appears elderly, trying to feed her baby, who is sucking on empty, wrinkled breasts. Another picture, taken in a psychiatric hospital in Beirut in 1982, shows a child curled up on a mattress, flies settled on his body. He is tied to the metal bedstead with string, to stop him wandering off amid the broken glass. There is no need to see or hear the bombs to understand their effect on the helpless, and the desperation of those who care for them.

The horrors of the battlefield are never far away in Tate Britain’s retrospective of Don McCullin’s work: the dead Khmer Rouge soldiers in a crater in Cambodia, Congolese soldiers tormenting freedom fighters in Stanleyville, young Christians on a bombed-out Beirut street, posing like a boy band over the body of a dead Palestinian girl. But McCullin has said again and again that he doesn’t like to be called a war photographer; preferring, simply, “photographer”. He is as interested in the people fighting wars as the people caught in their rip tide. “Starving Twenty Four Year Old Mother With Child” taken in Biafra in 1968, shows a woman, so gaunt she appears elderly, trying to feed her baby, who is sucking on empty, wrinkled breasts. Another picture, taken in a psychiatric hospital in Beirut in 1982, shows a child curled up on a mattress, flies settled on his body. He is tied to the metal bedstead with string, to stop him wandering off amid the broken glass. There is no need to see or hear the bombs to understand their effect on the helpless, and the desperation of those who care for them.

I’ve known Don McCullin for many years. He’s soft-spoken, occasionally gruff, but funny, too. He was born into poverty in north London, 83 years ago. His first published photograph, “The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits” (1958), shows some young men he’d been at school with standing in a bombed-out building. When the men were caught up in a fight, during which a policeman was stabbed to death, McCullin sensed an opportunity to sell the photograph to the press. The Observer newspaper bought it and a few years later, after seeing the pictures he had taken of a freshly divided Berlin, would offer him a job. It was clear that he had a special eye – and more than that, an empathy that travelled down the lens to his subjects, and was reflected back to his audience.

Over the decades he has wandered the world, from one atrocity to the next, documenting humanity and inhumanity. In between he has turned his lens on Britain: on the poverty of Bradford and London’s East End; the humour of the country at play; the naked beauty of the landscape around his home in Somerset.

More here.