by Robert Fay

Lake Simcoe, Canada. The sound of the Chickering piano. Bach.

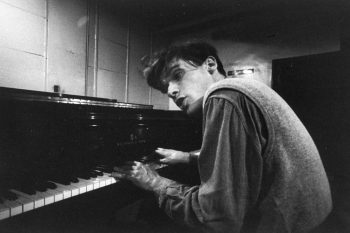

He is lazing down a wooded foot path, teasing his collie Banquo with a stick. He wears gloves, a wool Donegal cap, muffler and long coat despite the July temperatures. He is not being self-consciously eccentric; he simply fears getting a chill, and therefore sick. The film is black-and-white, giving the imagination ample room to conjure up the verdant rapacity of the brief northern growing season. He is then pictured inside the cottage seated before the Chickering, swaying and rocking as he alternately taps and presses the keys, his hands occasionally leaping back from the instrument as if caught in flagrante delicto.

The regal pianissimo of the Italian Concerto.

He is humming. He will always hum when he’s secluded within the architecture of the immortal scores. Recording engineers will despair of this harmonizing, but the microphones must be present, and he will sing as he plays, because the two expressions are a hypostatic union, an indivisible entity offering themselves to the music. He hums because the composition is only a series of notations until it becomes a part of his body, a force within, causing him to sway and vocalize the rapturous melody.

The cottage is the perfect bourgeois expression of respectable 1950s Toronto. It is not to be confused with a cabin. It is the weekend retreat of prosperous fir merchant, not a sportsman. And the Toronto of the 1950s is Victorian, hardworking and Protestant, and Glenn Gould will decide he can live nowhere else, despite his fame and financial success.

There are of course philistines in the city, but the Goulds are not among them. The cottage reflects cultivation and taste. It is carpeted and furnished with comfortable pieces, wicker chairs, table lamps, bookshelves, a floor model television set.

The 70-year-old Chickering is backed up to the picture window where outside one sees a stand of birch trees, a spruce, a recently cut lawn, and the rippling water of Lake Simcoe beyond. Level with the windowsill is a small table with a lamp and a tiny statuette of a doe resting on her hind legs. Next to the piano is a larger table with stacks of scores, and on the Chickering, there is an open score on the music rack, as well as a porcelain tea cup and saucer on the piano lid.

The documentary is called “Glenn Gould – Off the Record,” and it is a 30-minute piece filmed by the CBC in 1959.

It begins with Gould in New York at the Steinway & Sons headquarters in Manhattan. He is choosing a piano for an upcoming performance of Bach. The film then shifts to the family cottage at Lake Simcoe, 90 miles north of Toronto, before rejoining Gould in the basement of the Steinway building. The film includes footage from the tiny hamlet of Uptergrove, which is the closest town to the cottage. When Gould breaks away from his studies, he drives downtown for groceries and a meal at his favorite restaurant.

The proprietor of Adams General Store / Post Office (a wooden sign with a bottle cap graphic: “DRINK Pepsi Cola”) has known Gould since he was a child. He often finds crumpled dollars in the snow, and he sets them aside, knowing the young musician would have absently dropped them while deep in thought. When Gould returns to the Lake he will end up on a private dirt road that leads back down to the cottage. There is a pole with a hand-painted wood slate that reads: “R H GOULD – GLEN COVE.” It’s like that. It’s life in the country, and there in solitude, Gould’s imagination can pursue its contrapuntal impulses, free of interference or anxiety, entirely in control of circumstances.

In 1959 there were 17 million Canadians, now there are 35 million, and the film stands as something of an elegy to a Canadian way-of-life now disappearing. The land has more people on it than ever. There is more noise, and geographic solitude is harder to achieve. And this change would have been jarring for Gould, for whom solitude was essential to his life and art. His love-of-country rested, in part, on the sparsely populated north country.

His 1967 CBC radio program “The Idea of North,” profiled Canadians who had gone to live and work in the great solitude of the artic region, not simply as a way of making a living, but more as a matter of exploring the self. Yet in the Gouldian manner, the program wasn’t standard public-broadcasting fair, but an experiment in counterpoint. One Canadian voice begins talking of his experience, then a second voice is dropped in, and both “melodies” continue echoing and speaking to each in the manner of a Bach keyboard piece.

But counterpoint isn’t the focus of the film, and what remains with me are the more pedestrian details: Glenn’s lakeside neighbor cutting the grass with an old push reel mower, and the porcelain saucer and tea cup on the lid of his Chickering. This last detail is something I linger on with pleasure. It has something to do with memory and the loss of the little objects and rituals that were once the invisible DNA of our lives.

I am reminded of the now-defunct Greenhouse Coffee Shop on Brattle Street in Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It looked directly out at the Out of Town News kiosk and the outer bricks walls enclosing Harvard Yard. My first visit was in 1989. I was a high school kid from Boston’s North Shore and the small café with its Bohemian clientele was nothing less than my Paris, my Vienna, proof I could dream beyond the work-a-day America of my parents.

I remember the cigarette smoke in the café clung stubbornly to my clothes, and it wasn’t unusual to smell pipe tobacco too, as older gentlemen occasionally sparked up a full bent pipe. The coffee came in cups and saucers along with endless slices of cherry and apple pie from the countertop pie displays with heavy glass covers.

Ah, the cups and the saucers! It was a similar ritual visiting my mother’s Irish aunts in Boston. Neither of them had married, and like good Catholic women of the era, they had remained housemates for life and avoided the company of men. Aunt Libby and Aunt Mary had both been grade school teachers before they retired. On our visits, they served mother Lipton tea in a simple cup and saucer. I got ginger ale and a glass filled with crushed ice, or if was unlucky, a bottle of medicinal Moxie soda, which my aunts kept in the pantry for Grandpa’s high balls.

These two angelic women always wore dresses, black heels and thick-brown panty hoses. Aunt Mary still wore 1950s-era cat-eye glasses with a chain so she could rest them on her chest when not reading. There was sense of order and refinement about the house: stained glass lamp shades, candy dishes with stale pastel mints, ottomans, Lladro figurines and plastic covering the sofa. I wish I could time travel back to their kindness, their gentle manners, their unconscious preservation of 1950s America—still alive in their parlor as late as 1974—but it’s gone now, and gone forever.

*

Toward the end of the film the cup and saucer has disappeared. Gould is seated at the piano while his friend Franz Kraemer, a musician and radio producer, sits nearby in a comfortable white wicker chair with his legs languorously crossed. They are talking about the atonal master Anton Webern, and Kraemer says he has was a student of Webern’s in Vienna. He adds that Webern was a shy man who wrote shy music, and Gould immediately interjects, “Is this shy music?” and then turns to the keyboard and plays a few bars of a halting, disjointed piece of Webern music. It’s all so perfect: the cottage, the piano, the artist in the deep woods, the intellectual companionship of a good friend, the piles of scores stacked and scattered about.

How I envy such a life! A life of the mind, art, good companionship, and all in the leafy summer retreat!

The voice of the narrator periodically cuts in to provide context for Gould’s life and career. “Gould’s life seems ideal: peace, calm, time to study in idyllic surroundings,” the omniscient voice informs us. “But his world is also an unnerving one. It takes courage of a high order to play Beethoven before the super critical audience of Berlin. Or to present oneself on the same platform as the great Russian pianists of today.”

Gould was touring in those years and despised it. He mistrusted audiences, despaired at the imperfections inherent in live performances, and suffered under the vagaries of travel. Plus, there were the obligatory social demands surrounding the concert appearance: dinners, speeches, receptions with benefactors and subscribers. As often as he could, Gould canceled performances—frequently at the last moment—citing illness, though most likely these were hypochondrial episodes.

Life at Lake Simcoe was indeed idyllic for Glenn, but it was lived as stolen time, a temporary respite from the concert-going vultures in the great cities of the world. It wasn’t until 1964, five years later, when Gould finally had the financial leverage to quit touring and reserve himself for the studio to record, rearrange, perfect, snip and playback his music, and ultimately his life, in the way that he saw fit.

*

The documentary ends where it begin, in the Steinway & Sons basement, Gould scrupoulsly investigating all the concert grands. He eventually settles on a piano with the “the agility” he requires to play Bach. The piano tuner and the Steinway account manger stand with him chatting, clearly enjoying his company.

But Gould must be alone, there is no other way. He politely asks, “Can I stay and practice?” and the two men immediately depart, saying they’ll be upstairs if he needs anything. He begins playing Bach as the credits roll.

The rocking and swaying slowly starts. I think of religious Jews swaying (shucklen in Yiddish) as they read the Torah, entering into the ancient and mystical landscapes of God. As in the Psalms: “All my limbs shall say ‘Who is like You, O Lord?’”

Gould was not Jewish, nor a religious protestant, but Bach got him swaying, got him back to the Chickering and Lake Simcoe and those joyful days of child solitude at the cottage, the cups and saucers, and I remember that wonder too, of childhood moments, when the world came to you—served right up to you—as if to give you a taste of heaven, of more to come, of a life that seemed to promise imagination, wonders, adventure, everything!

Robert Fay’s essays, reviews and stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Millions, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly Review, among others. He is co-creator of the Feeling Bookish Podcast. Follow him on Twitter @RobertFay1.