Month: January 2019

Nicola L (1932 [or 1937] – 2019)

Sunday Poem

By a poverty of vision a

wealth of calamity occurs.

…….…………….—Roshi Bob

I Know a Man

As I sd to my

friend, because I am

always talking, —John, I

sd, which was not his

name, the darkness sur-

rounds us, what

can we do against

it, or else, shall we &

why not, buy a goddamn big car,

drive, he sd, for

christ’s sake, look

out where you’re going

Robert Creeley

from Contemporary American Poetry

Penguin Books, 1966

Complete Axolotl Genome Could Reveal the Secret of Regenerating Tissues

Joshua Rapp Learn in Smithsonian:

When Lake Xochimilco near Mexico City was Lake Texcoco, and the Aztecs founded their island capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1325, a large aquatic salamander thrived in the surrounding lake. The axolotl has deep roots in Aztec religion, as the god Xolotl, for whom the animal is named, was believed to have transformed into an axolotl—although it didn’t stop the Aztecs from enjoying a roasted axolotl from time to time. The custom of eating axolotl continues to this day, although the species has become critically endangered in the wild. Saving the salamander that Nature called “biology’s beloved amphibian” takes on a special significance given the animal’s remarkable traits. Axolotls are neotenic, meaning the amphibians generally do not fully mature like other species of salamander, instead retaining their gills and living out their lives under water as a kind of juvenile. On rare occasions, or when stimulated in the lab, an axolotl will go through metamorphosis and develop lungs to replace its gills.

When Lake Xochimilco near Mexico City was Lake Texcoco, and the Aztecs founded their island capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1325, a large aquatic salamander thrived in the surrounding lake. The axolotl has deep roots in Aztec religion, as the god Xolotl, for whom the animal is named, was believed to have transformed into an axolotl—although it didn’t stop the Aztecs from enjoying a roasted axolotl from time to time. The custom of eating axolotl continues to this day, although the species has become critically endangered in the wild. Saving the salamander that Nature called “biology’s beloved amphibian” takes on a special significance given the animal’s remarkable traits. Axolotls are neotenic, meaning the amphibians generally do not fully mature like other species of salamander, instead retaining their gills and living out their lives under water as a kind of juvenile. On rare occasions, or when stimulated in the lab, an axolotl will go through metamorphosis and develop lungs to replace its gills.

Accompanying these unique traits is a remarkably complex genome, with 32 billion base pairs compared to about 3 billion base pairs in human DNA. The axolotl has the largest genome ever fully sequenced, first completed last year by a team of European scientists. The University of Kentucky, which heads axolotl research in the United States, today announced that researchers have added the sequencing of whole chromosomes to the European effort—“about a thousand-fold increase in the length of assembled pieces,” according to Jeremiah Smith, an associate biology professor at the University of Kentucky. Scientists hope to use this new data to harness some of the axolotl’s unique abilities.

More here.

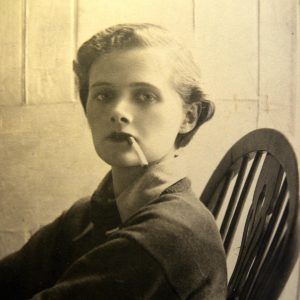

A Series of Selves

Colin Dickey in The New Republic:

Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

They revealed a Woolf unexpectedly playful and at times mundane: “So now I have assembled my facts,” she wrote on August 22, 1922, “to which I now add my spending 10/6 on photographs, which we developed in my dress cupboard last night; & they are all failures. Compliments, clothes, building, photography—it is for these reasons that I cannot write Mrs Dalloway.” They also reveal a Woolf at times both vicious and shitty: her cattiness, her casual racism. Ruth Gruber, who wrote the first PhD dissertation on Woolf, had a short, pleasant correspondence with her in the 1930s, only to discover, when the diaries were later published, Woolf referring to her dismissively as a “German Jewess” (Gruber was born in Brooklyn). As Gruber would write of the experience, “Diaries can rip the masks from their creators.”

Unlike many writers’ diaries, The Diary of Virginia Woolf has become more than just a gloss on her novels; it is a work of literature in and of itself, a powerful and startling look into the inner life of a woman writer during a dramatic time. “I will not be ‘famous,’ ‘great,’” she wrote in 1933. “I will go on adventuring, changing, opening my mind and my eyes, refusing to be stamped and stereotyped. The thing is to free one’s self: to let it find its dimensions, not be impeded.” Woolf began writing in a diary in 1897, when she was just 14 years old; she would continue on and off again, for the rest of her life; she would write the final entry four days before her death in March 1941. In total, she wrote over 770,000 words in her diaries alone.

More here.

What is truth? On Ramsey, Wittgenstein, and the Vienna Circle

Cheryl Misak in Aeon:

Vienna in the 1920s was an exciting place. Politically, it was the time of Red Vienna, when the municipal government experimented with radical democratic reforms in housing, healthcare, education and worker’s rights. There was optimism in the air, despite postwar hyperinflation and rising conservatism. It was also an exciting time intellectually, for one of the most influential movements in the history of philosophy was in full swing: the Vienna Circle.

They were a group of philosophers, mathematicians and physicists who gathered around the German philosopher Moritz Schlick, and included luminaries such as Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath and Herbert Feigl. The Circle put forward an ambitious programme that would have all knowledge constructed out of an objective foundation of observation and deductive logic. Their ‘verifiability principle’ would assert that a meaningful sentence had to be reducible, via truth-preserving logic, to a basic language of observation statements. Metaphysics, ethics, religion and aesthetics were either to be revised so as to be stated in this scientific language, or else declared meaningless – mere nonsense. These new scientific philosophers were socially progressive, at home in Red Vienna, and they saw themselves as intellectually progressive as well. Unfortunately, others all too readily concurred, such as the fascist student who gunned down Schlick on the steps of the University of Vienna in 1936.

Theirs was an idea whose time had come. A similar group was developing in Berlin, with Hans Reichenbach and Carl Hempel as its most prominent members. In Cambridge, Bertrand Russell had also been arguing that philosophy must proceed by a logical analysis that bottoms out in simple, metaphysically fundamental existents in the world. But it was Russell’s Viennese student Ludwig Wittgenstein who most intrigued the Circle with his first book, written mostly during the First World War on the perilous Eastern and Italian fronts, where he was ultimately taken as a prisoner of war.

More here.

No One Is Prepared for Hagfish Slime

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

At first glance, the hagfish—a sinuous, tubular animal with pink-grey skin and a paddle-shaped tail—looks very much like an eel. Naturalists can tell the two apart because hagfish, unlike other fish, lack backbones (and, also, jaws). For everyone else, there’s an even easier method. “Look at the hand holding the fish,” the marine biologist Andrew Thaler once noted. “Is it completely covered in slime? Then, it’s a hagfish.”

Hagfish produce slime the way humans produce opinions—readily, swiftly, defensively, and prodigiously. They slime when attacked or simply when stressed. On July 14, 2017, a truck full of hagfish overturned on an Oregon highway. The animals were destined for South Korea, where they are eaten as a delicacy, but instead, they were strewn across a stretch of Highway 101, covering the road (and at least one unfortunate car) in slime.

Typically, a hagfish will release less than a teaspoon of gunk from the 100 or so slime glands that line its flanks. And in less than half a second, that little amount will expand by 10,000 times—enough to fill a sizable bucket.

More here.

Rationality: research shows we’re not as stupid as we have been led to believe

George Farmer and Paul Warren in The Conversation:

Rationality has long been an important concept in the study of judgement and decision making. The highly influential work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky comprehensively showed that we often fail to make rational decisions – such as worrying about a terrorist attack but not about crossing the road.

Rationality has long been an important concept in the study of judgement and decision making. The highly influential work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky comprehensively showed that we often fail to make rational decisions – such as worrying about a terrorist attack but not about crossing the road.

But this failure is based on a strict interpretation of what it is to be rational – obeying the laws of logic and probability. It is not interested in the machine that must weigh up the evidence and reach a decision. In our case, that machine is the human brain – and like any physical system, it has its limits.

Although our decision making falls short of the standards required by logic and mathematics, there is still a role for rationality in understanding human cognition. The psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer has shown that while many of the heuristics we use may not be perfect, they are both useful and efficient.

But a recent approach called computational rationality goes a step further, borrowing an idea from artificial intelligence. It suggests that a system with limited abilities can still take an optimal course of action.

More here.

A look back at Hipsters vs. Nerds

Without Workers, We Wouldn’t Have Democracy

Shawn Gude in Jacobin:

Discussions about the state of democracy are suddenly all the rage. And it’s not hard to see why: Bolsonaro in Brazil, Trump in the US, Erdoğan in Turkey, Orbán in Hungary — all point to a resurgent authoritarianism and a diminution of democratic forms. But we can’t understand the current retrenchment without understanding how mass democracy came about in the first place.

Discussions about the state of democracy are suddenly all the rage. And it’s not hard to see why: Bolsonaro in Brazil, Trump in the US, Erdoğan in Turkey, Orbán in Hungary — all point to a resurgent authoritarianism and a diminution of democratic forms. But we can’t understand the current retrenchment without understanding how mass democracy came about in the first place.

In Capitalist Development and Democracy, first published in 1992, a trio of scholars (Evelyne Huber, John Stephens, and Dietrich Rueschemeyer) provide a sweeping examination of democracy’s rise in the twentieth century across three regions: Europe, North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Breaking from the conventional story, they argue that capitalism has been crucial to democracy’s ascension not because of its natural symbiosis with popular government, but because it breaks up traditional power structures and generates a larger, more organizable working class. “Capitalism,” they write, “creates democratic pressures in spite of capitalists, not because of them.”

Huber and her coauthors pay special attention to how distributions of power, both domestically and internationally, have opened up or closed off democratic struggles.

More here.

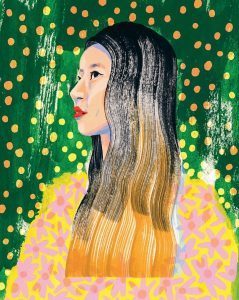

Sally Wen Mao’s Visionary Poems

Dan Chiasson at The New Yorker:

Sally Wen Mao’s new book of poems, “Oculus,” borrows its slightly menacing title from the Latin word for “eye,” which also refers to, among other things, a virtual-reality company and the eye-shaped skylight at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. There are eyes everywhere in “Oculus,” but not all of them are blessed with sight. Some are all-seeing, panoptic; others are yearning and blinkered, unable to return the gaze they attract. These poems are haunted by images of human faces staring out from all kinds of screens, faces that are themselves screens upon which the world projects its fantasies and anxieties. “The stories about our lives do not have faces,” Mao writes. Her strange and morally succinct book is, in part, a sustained defense of writing. Mao’s poems intervene in a culture glutted with visual images, on behalf of what she calls “the self you want to hide”—the “sad, pretty thing,” lost behind the images. “Because being seen,” she writes elsewhere, “has a different meaning to someone / with my face.”

Sally Wen Mao’s new book of poems, “Oculus,” borrows its slightly menacing title from the Latin word for “eye,” which also refers to, among other things, a virtual-reality company and the eye-shaped skylight at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. There are eyes everywhere in “Oculus,” but not all of them are blessed with sight. Some are all-seeing, panoptic; others are yearning and blinkered, unable to return the gaze they attract. These poems are haunted by images of human faces staring out from all kinds of screens, faces that are themselves screens upon which the world projects its fantasies and anxieties. “The stories about our lives do not have faces,” Mao writes. Her strange and morally succinct book is, in part, a sustained defense of writing. Mao’s poems intervene in a culture glutted with visual images, on behalf of what she calls “the self you want to hide”—the “sad, pretty thing,” lost behind the images. “Because being seen,” she writes elsewhere, “has a different meaning to someone / with my face.”

more here.

The Final Days of EMI

John Harris at The Guardian:

In the summer of 1965, the Rolling Stones released “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”. On the US version, its B-side was a makeweight piece titled “The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man”, which directed sneering contempt on some poor unfortunate who worked for the group’s record label: “I promo groups when they come into town / Well they laugh at my toupee, they’re sure to put me down.”

In the summer of 1965, the Rolling Stones released “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”. On the US version, its B-side was a makeweight piece titled “The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man”, which directed sneering contempt on some poor unfortunate who worked for the group’s record label: “I promo groups when they come into town / Well they laugh at my toupee, they’re sure to put me down.”

Thus began a lineage of rock songs founded on the eternal contradiction between the artistic impulse and the hucksterish, often seedy ways of the music business. This reached a peak of fury and cynicism in the era of punk with the Sex Pistols’ gloriously incoherent classic “EMI”, in which John Lydon vents his rage at the company that put out the group’s first single in 1976, only to dump them. “It’s an unlimited supply,” he spits. “And there is no reason why / I tell you it was all a frame / They only did it ’cos of fame / Who? / EMI!”

more here.

Finding Redemption in Daphne Du Maurier’s Cornwall

Kitty Wenham at The Quarterly Conversation:

The beating heart of it all, Du Maurier’s estate Menabilly, remains a secret few have been allowed to penetrate. Nestled behind locked gates, a visitor would find it impossible to catch even a glimpse of its infamous facade from the roadside. Nearby is the town of Fowey. Another great love. Once referred to as Du Maurier’s ‘salvation’, it is the picture of gentle tranquillity. By a twinkling blue estuary lined with quaint white cottages, you can glance at her other famous home —Ferryside. The coves are full of families, the beaches always busy. Journey on for forty minutes more, and you might stumble across the infamous Jamaica Inn. Far from an isolated hub of menacing activity and excitement, it now stands on a busy motorway leading out of Cornwall — an impersonal, family stop on the way back from a typical summer road trip.

The beating heart of it all, Du Maurier’s estate Menabilly, remains a secret few have been allowed to penetrate. Nestled behind locked gates, a visitor would find it impossible to catch even a glimpse of its infamous facade from the roadside. Nearby is the town of Fowey. Another great love. Once referred to as Du Maurier’s ‘salvation’, it is the picture of gentle tranquillity. By a twinkling blue estuary lined with quaint white cottages, you can glance at her other famous home —Ferryside. The coves are full of families, the beaches always busy. Journey on for forty minutes more, and you might stumble across the infamous Jamaica Inn. Far from an isolated hub of menacing activity and excitement, it now stands on a busy motorway leading out of Cornwall — an impersonal, family stop on the way back from a typical summer road trip.

I first came to Cornwall searching for Daphne Du Maurier in August 2013, the first of many family trips to the coast. I imagined the high, thrashing waves of the sea, the ruined mansions, the wild landscape untamed, overrunning every bend in the road. Instead, I found Cornwall to be a place of solitude.

more here.

‘BlacKkKlansman’ Was The Most Frighteningly Accurate Movie Of 2018

Talia Lavin in Huffington Post:

2018 was a year overstuffed with culture. That’s just the way it is now, movies and TV and songs and memes and thoughtful features and endless, endless politics scrolling past our weary eyes at the speed of silicon and too-blue light. But in all the chaos there’s a moment where my hazy memories of frenetic consumption pause, for a piece of filmmaking that called on me to think hard and to remember. That movie was Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman.” It’s currently raking in a modest haul of awards, but for me, it’s going to linger long past the last bottle of popped January 1st champagne, a remarkable slice of light to which I’ll return for years to come.

2018 was a year overstuffed with culture. That’s just the way it is now, movies and TV and songs and memes and thoughtful features and endless, endless politics scrolling past our weary eyes at the speed of silicon and too-blue light. But in all the chaos there’s a moment where my hazy memories of frenetic consumption pause, for a piece of filmmaking that called on me to think hard and to remember. That movie was Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman.” It’s currently raking in a modest haul of awards, but for me, it’s going to linger long past the last bottle of popped January 1st champagne, a remarkable slice of light to which I’ll return for years to come.

Much has been said about the film ― its ambition, historicity and panache have been amply noted. But I’ve elected to discuss it here because I admire it as a piece of artistry and as a salvo launched at the perfect cultural moment. he film is about a pioneering black cop who confronts the Ku Klux Klan, providing the voice of a would-be Klansman on the phone while his Jewish co-worker offers a white body to attend the meetings in person. Any summary would be a bare gesture at the substance of the movie, which deftly conjures up the early 1970s with both winking kitsch and careful verisimilitude. “BlacKkKlansman” delivers more than any blockbuster ever needs to, filling its slick packaging with layers of complexity that Hollywood rarely allows for. The film addresses the conditional whiteness of Jews in America; the ways in which the presumed fragility of white womanhood can provide a shield for those who would do violence; the vitality of student activism, and the way it forms an irresistible target for those who would silence dissent; and the role of music, rhetoric and film itself in shaping black and white identities. It does all this and so much more, wrapped in a compulsively watchable package.

There’s a bravura quality to it, a bracing reminder of the need to combat racism in both its most overt guises ― Klansmen burning crosses ― and its subtler incarnations, as when rookie black cop Ron Stallworth faces an array of racist behaviors at his new workplace, from skepticism to outright slurs.

More here.

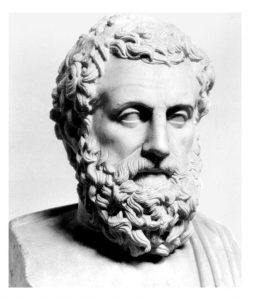

Need a New Self-Help Guru? Try Aristotle

John Kaag in The New York Times:

Three years ago, New Year’s came and I promised to eat only organic. I lasted two weeks. A year ago, I resolved to run before dawn and take a cold shower every morning. That lasted two days. This year, I don’t have a resolution. Instead I read Edith Hall’s “Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life,” and concluded I probably didn’t have to undergo some painful — and therefore temporary — transformation to remake my life. I just had to put some sustained effort into being properly happy.

Three years ago, New Year’s came and I promised to eat only organic. I lasted two weeks. A year ago, I resolved to run before dawn and take a cold shower every morning. That lasted two days. This year, I don’t have a resolution. Instead I read Edith Hall’s “Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life,” and concluded I probably didn’t have to undergo some painful — and therefore temporary — transformation to remake my life. I just had to put some sustained effort into being properly happy.

There is a pernicious, but widely held, belief that turning over a new leaf always involves turning our worlds upside down, that living a happy, well-adjusted life entails acts of monkish discipline or heroic strength. The genre of self-help lives and dies on this fanaticism: We should eat like cave men, scale distant mountains, ingest live charcoal, walk across scalding stones, lift oversize tires, do yoga in a hothouse, run a marathon, run another. In our culture, virtuous moderation and prudence rarely sell but, taking her cues from Aristotle, Hall offers a set of reasons to explain why they should.

Hall’s new book clears a rare middle way for her reader to pursue happiness, what the ancient Greeks called eudaimonia, usually translated as well-being or prosperity. This prosperity has nothing to do with the modern obsession with material success but rather “finding a purpose in order to realize your potential and working on your behavior to become the best version of yourself.” It sounds platitudinous enough, but it isn’t, thanks to Hall’s tight yet modest prose. “Aristotle’s Way” carefully charts the arc of a virtuous life that springs from youthful talent, grows by way of responsible decisions and self-reflection, finds expression in mature relationships, and comes to rest in joyful retirement and a quietly reverent death. Easier said than done, but Aristotle, Hall explains, is there to help.

More here.

Memories of Irish Birdsong

Liam Heneghan in The Irish Times:

1. My mother once saw the chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs; in Irish: “Rí Rua”) take a shit on Grafton Street and she scolded him. He just kept repeating his distinctive call “pink, pink, pink, trup,” over and over again, but you could kinda tell that he was mortified. Good bird, really; had trouble later with the auld drugs, and got very stout. Died way too young. In the eighties, those birds had a string of great hits.

1. My mother once saw the chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs; in Irish: “Rí Rua”) take a shit on Grafton Street and she scolded him. He just kept repeating his distinctive call “pink, pink, pink, trup,” over and over again, but you could kinda tell that he was mortified. Good bird, really; had trouble later with the auld drugs, and got very stout. Died way too young. In the eighties, those birds had a string of great hits.

2. I worked one summer on the Cork Train on the food trolley. A young fella with me in the kitchen car was really into the skylark (Alauda arvensis, in Irish: “Fuiseog”). He could play skylark’s famous guitar riff on his knock-off Les Paul (you know the one, it goes “chirrup… chirrup, trrrp”). Claimed the skylark did not play a real Gibson either. I will never forget that little detail; I lost touch with that kid later on.

3. Back in the day, I’d hear corncrakes (Crex crex; in Irish: “Traonach”) along the Co Mayo coast all the time. They are a rare breed now, of course; almost extinct. Once when I was pushing my bike up a laneway I saw the corncrake standing with his sister outside a cottage. He must have thought I had looked at his sister funny, as he snarled “kerrx-kerrx” at me and started to fling his droppings. I was told afterwards that the whole family was mad. Brothers all musicians in America.

More here.

The Uncertain Future of Particle Physics

Sabine Hossenfelder in the New York Times:

The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest particle accelerator. It’s a 16-mile-long underground ring, located at CERN in Geneva, in which protons collide at almost the speed of light. With a $5 billion price tag and a $1 billion annual operation cost, the L.H.C. is the most expensive instrument ever built — and that’s even though it reuses the tunnel of an earlier collider.

The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest particle accelerator. It’s a 16-mile-long underground ring, located at CERN in Geneva, in which protons collide at almost the speed of light. With a $5 billion price tag and a $1 billion annual operation cost, the L.H.C. is the most expensive instrument ever built — and that’s even though it reuses the tunnel of an earlier collider.

The L.H.C. has collected data since September 2008. Last month, the second experimental run completed, and the collider will be shut down for the next two years for scheduled upgrades. With the L.H.C. on hiatus, particle physicists are already making plans to build an even larger collider. Last week, CERN unveiled plans to build an accelerator that is larger and far more powerful than the L.H.C. — and would cost over $10 billion.

I used to be a particle physicist. For my Ph.D. thesis, I did L.H.C. predictions, and while I have stopped working in the field, I still believe that slamming particles into one another is the most promising route to understanding what matter is made of and how it holds together. But $10 billion is a hefty price tag. And I’m not sure it’s worth it.

More here.

The strange tension between humans’ love of making animals family members and serving them as a main course

The Existential Englishman: Paris Among the Artists

Alexander Larman in The Guardian:

Michael Peppiatt’s memoir is subtitled Paris Among the Artists, but it could be called A Portrait of the Art Critic As an Older Man. Peppiatt, who is best known for his biography and memoirs of his friend Francis Bacon, has spent the greater part of his working life in Paris, and this book is a love letter to the city, although not an uncritical one. He writes in the preface that he will explore “my lifelong attachment to this bewitching, temperamental, exasperating city and the deep love-hate relationship that binds me to it”. Yet he is ultimately a romantic, and the scent that rises from these pages is a heady aroma of Gauloises and red wine. Peppiatt, as a young man, was rather fond of the bottle; this book, at its best, has a similarly intoxicating quality, if one allows for the inevitable moments of self-absorption.

Michael Peppiatt’s memoir is subtitled Paris Among the Artists, but it could be called A Portrait of the Art Critic As an Older Man. Peppiatt, who is best known for his biography and memoirs of his friend Francis Bacon, has spent the greater part of his working life in Paris, and this book is a love letter to the city, although not an uncritical one. He writes in the preface that he will explore “my lifelong attachment to this bewitching, temperamental, exasperating city and the deep love-hate relationship that binds me to it”. Yet he is ultimately a romantic, and the scent that rises from these pages is a heady aroma of Gauloises and red wine. Peppiatt, as a young man, was rather fond of the bottle; this book, at its best, has a similarly intoxicating quality, if one allows for the inevitable moments of self-absorption.

Peppiatt was brought up to be bilingual, because his father believed that he stood a better chance of getting on in the world if he spoke French. His faith was rewarded when his son obtained a job at the culture magazine Réalités in 1964, from where he headed to the English-language version of Le Mondeand then to Art International, which he both published and edited. He accomplished this, as well as writing numerous books about art, with an air of cultured insouciance. Yet, as he notes, “the luxuries, the grandeurs, have no meaning without the drudgery and misères of the daily round”. It must be said that Peppiatt’s luxuries and grandeurs are rather more grand than the rest of us might expect. When he writes about drinking champagne at the Paris Ritz, or being led on grand bacchanals by famous chums, it is hard not to feel that Peppiatt has led an unusually gilded existence.

More here.

General Strikes, Explained

Kim Kelly in Teen Vogue:

The word strike seems to be on everyone’s lips these days. Workers across the world have been striking to protest poor working conditions, to speak out against sexual harassment, and to jumpstart stalled union negotiations. And as we just saw with the Los Angeles teachers’ successful large-scale strike, which spanned six school days, strikers have been winning. Despite the shot of energy that organized strikes have injected into the labor movement, many people aren’t content with run-of-the-mill work stoppages, or even with more militant wildcat strikes.

The word strike seems to be on everyone’s lips these days. Workers across the world have been striking to protest poor working conditions, to speak out against sexual harassment, and to jumpstart stalled union negotiations. And as we just saw with the Los Angeles teachers’ successful large-scale strike, which spanned six school days, strikers have been winning. Despite the shot of energy that organized strikes have injected into the labor movement, many people aren’t content with run-of-the-mill work stoppages, or even with more militant wildcat strikes.

As President Donald Trump’s scandal-plagued government shutdown stretches into its fourth week and more than 800,000 federal workers struggle to survive sans paychecks, the words general strike have begun appearing with increasing frequency on social media and in a spate of articles. On January 20, Association of Flight Attendants-CWA President Sara Nelson suggested that a general strike could potentially end the government shutdown. The fact that a labor union official is speaking about such drastic action now is very significant, for one thing because there has not been a major U.S. general strike since the government cracked down on labor following 1946’s Oakland general strike. Also, a general strike is an incredibly massive undertaking; while many organized industry-specific strikes can comprise hundreds or even thousands of workers, a general strike could potentially involve millions.

So what does it all mean? How is a general strike different from a planned, industry-specific work stoppage; why are people interested in the idea now; and what would one look like in 2019?

More here.