Jonathan Shaw in Harvard Magazine:

IN MARCH 18, 2018, at around 10 P.M., Elaine Herzberg was wheeling her bicycle across a street in Tempe, Arizona, when she was struck and killed by a self-driving car. Although there was a human operator behind the wheel, an autonomous system—artificial intelligence—was in full control. This incident, like others involving interactions between people and AI technologies, raises a host of ethical and proto-legal questions. What moral obligations did the system’s programmers have to prevent their creation from taking a human life? And who was responsible for Herzberg’s death? The person in the driver’s seat? The company testing the car’s capabilities? The designers of the AI system, or even the manufacturers of its onboard sensory equipment?

IN MARCH 18, 2018, at around 10 P.M., Elaine Herzberg was wheeling her bicycle across a street in Tempe, Arizona, when she was struck and killed by a self-driving car. Although there was a human operator behind the wheel, an autonomous system—artificial intelligence—was in full control. This incident, like others involving interactions between people and AI technologies, raises a host of ethical and proto-legal questions. What moral obligations did the system’s programmers have to prevent their creation from taking a human life? And who was responsible for Herzberg’s death? The person in the driver’s seat? The company testing the car’s capabilities? The designers of the AI system, or even the manufacturers of its onboard sensory equipment?

“Artificial intelligence” refers to systems that can be designed to take cues from their environment and, based on those inputs, proceed to solve problems, assess risks, make predictions, and take actions. In the era predating powerful computers and big data, such systems were programmed by humans and followed rules of human invention, but advances in technology have led to the development of new approaches. One of these is machine learning, now the most active area of AI, in which statistical methods allow a system to “learn” from data, and make decisions, without being explicitly programmed. Such systems pair an algorithm, or series of steps for solving a problem, with a knowledge base or stream—the information that the algorithm uses to construct a model of the world.

Ethical concerns about these advances focus at one extreme on the use of AI in deadly military drones, or on the risk that AI could take down global financial systems. Closer to home, AI has spurred anxiety about unemployment, as autonomous systems threaten to replace millions of truck drivers, and make Lyft and Uber obsolete. And beyond these larger social and economic considerations, data scientists have real concerns about bias, about ethical implementations of the technology, and about the nature of interactions between AI systems and humans if these systems are to be deployed properly and fairly in even the most mundane applications.

More here.

According to the UK’s

According to the UK’s  American stories trace the sweep of history, but their details are definingly particular. In the summer of 1979, Elizabeth Anderson, then a rising junior at Swarthmore College, got a job as a bookkeeper at a bank in Harvard Square. Every morning, she and the other bookkeepers would process a large stack of bounced checks. Businesses usually had two accounts, one for payroll and the other for costs and supplies. When companies were short of funds, Anderson noticed, they would always bounce their payroll checks. It made a cynical kind of sense: a worker who was owed money wouldn’t go anywhere, or could be replaced, while an unpaid supplier would stop supplying. Still, Anderson found it disturbing that businesses would write employees phony checks, burdening them with bounce fees. It appeared to happen all the time.

American stories trace the sweep of history, but their details are definingly particular. In the summer of 1979, Elizabeth Anderson, then a rising junior at Swarthmore College, got a job as a bookkeeper at a bank in Harvard Square. Every morning, she and the other bookkeepers would process a large stack of bounced checks. Businesses usually had two accounts, one for payroll and the other for costs and supplies. When companies were short of funds, Anderson noticed, they would always bounce their payroll checks. It made a cynical kind of sense: a worker who was owed money wouldn’t go anywhere, or could be replaced, while an unpaid supplier would stop supplying. Still, Anderson found it disturbing that businesses would write employees phony checks, burdening them with bounce fees. It appeared to happen all the time. This past week, Dr. Mark Green, M.D., who was recently elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state of Tennessee declared: “Let me say this about

This past week, Dr. Mark Green, M.D., who was recently elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state of Tennessee declared: “Let me say this about  The demand that we

The demand that we  Look around on your next plane trip. The iPad is the new pacifier for babies and toddlers. Younger school-aged children read stories on smartphones; older boys don’t read at all, but hunch over video games. Parents and other passengers read on Kindles or skim a flotilla of email and news feeds. Unbeknownst to most of us, an invisible, game-changing transformation links everyone in this picture: the neuronal circuit that underlies the brain’s ability to read is subtly, rapidly changing – a change with implications for everyone from the pre-reading toddler to the expert adult.

Look around on your next plane trip. The iPad is the new pacifier for babies and toddlers. Younger school-aged children read stories on smartphones; older boys don’t read at all, but hunch over video games. Parents and other passengers read on Kindles or skim a flotilla of email and news feeds. Unbeknownst to most of us, an invisible, game-changing transformation links everyone in this picture: the neuronal circuit that underlies the brain’s ability to read is subtly, rapidly changing – a change with implications for everyone from the pre-reading toddler to the expert adult. The 116th Congress, the members of which were officially sworn in on Thursday, contains

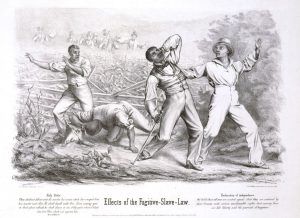

The 116th Congress, the members of which were officially sworn in on Thursday, contains  The Civil War began over one basic issue: Was slavery, the ownership of human beings, a legitimate national institution, fixed in national law by the United States Constitution? One half of the country said it was, the other said it was not. The ensuing conflict was the chief instigator of Southern secession, as the secessionists themselves proclaimed. It was thus the chief source of the war that led to slavery’s abolition in the United States. The struggle over property in slaves focused largely on the fate of the Western territories, but it also inflamed conflicts over the status of fugitive slaves. Pro-slavery Southerners insisted that the federal government was obliged to capture slaves who had escaped to free states and return them to their masters, and thus vindicate the masters’ absolute property rights in humans. Antislavery Northerners, denying that obligation and those supposed rights, saw the fugitives as heroic refugees from bondage, and resisted federal interference fiercely and sometimes violently. Even more than the fights over the territories, Andrew Delbanco asserts in “The War Before the War,” the “dispute over fugitive slaves … launched the final acceleration of sectional estrangement.”

The Civil War began over one basic issue: Was slavery, the ownership of human beings, a legitimate national institution, fixed in national law by the United States Constitution? One half of the country said it was, the other said it was not. The ensuing conflict was the chief instigator of Southern secession, as the secessionists themselves proclaimed. It was thus the chief source of the war that led to slavery’s abolition in the United States. The struggle over property in slaves focused largely on the fate of the Western territories, but it also inflamed conflicts over the status of fugitive slaves. Pro-slavery Southerners insisted that the federal government was obliged to capture slaves who had escaped to free states and return them to their masters, and thus vindicate the masters’ absolute property rights in humans. Antislavery Northerners, denying that obligation and those supposed rights, saw the fugitives as heroic refugees from bondage, and resisted federal interference fiercely and sometimes violently. Even more than the fights over the territories, Andrew Delbanco asserts in “The War Before the War,” the “dispute over fugitive slaves … launched the final acceleration of sectional estrangement.” WHAT IF KNOWLEDGE — the real, redeeming variety — is not power, but the opposite of it? If, for instance, to become properly human we need to run away from power as much as we can? Indeed, what if our highest accomplishment in this world came from radical self-effacement, the lowest existential station we could possibly reach?

WHAT IF KNOWLEDGE — the real, redeeming variety — is not power, but the opposite of it? If, for instance, to become properly human we need to run away from power as much as we can? Indeed, what if our highest accomplishment in this world came from radical self-effacement, the lowest existential station we could possibly reach? All revolutions come to an end, whether they succeed or fail.

All revolutions come to an end, whether they succeed or fail. Arundhati Roy: That was fourteen years ago! The updates now would include the ways in which big capital uses racism, caste-ism (the Hindu version of racism, more elaborate, and sanctioned by the holy books), and sexism and gender bigotry (sanctioned in almost every holy book) in intricate and extremely imaginative ways to reinforce itself, protect itself, to undermine democracy, and to splinter resistance. It doesn’t help that there has been a failure on the part of the left in general to properly address these issues. In India, caste—that most brutal system of social hierarchy—and capitalism have fused into a dangerous new alloy. It is the engine that runs modern India. Understanding one element of the alloy and not the other doesn’t help. Caste is not color-coded. If it were, if it were visible to the untrained eye, India would look very much like a country that practices apartheid.

Arundhati Roy: That was fourteen years ago! The updates now would include the ways in which big capital uses racism, caste-ism (the Hindu version of racism, more elaborate, and sanctioned by the holy books), and sexism and gender bigotry (sanctioned in almost every holy book) in intricate and extremely imaginative ways to reinforce itself, protect itself, to undermine democracy, and to splinter resistance. It doesn’t help that there has been a failure on the part of the left in general to properly address these issues. In India, caste—that most brutal system of social hierarchy—and capitalism have fused into a dangerous new alloy. It is the engine that runs modern India. Understanding one element of the alloy and not the other doesn’t help. Caste is not color-coded. If it were, if it were visible to the untrained eye, India would look very much like a country that practices apartheid.

In early 2017, epidemiologist Rory Collins at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and his team faced a test of their principles. They run the UK Biobank (UKB), a huge research project probing the health and genetics of 500,000 British people. They were planning their most sought-after data release yet: genetic profiles for all half-million participants. Three hundred research groups had signed up to download 8 terabytes of data—the equivalent of more than 5000 streamed movies. That’s enough to tie up a home computer for weeks, threatening a key goal of the UKB: to give equal access to any qualified researcher in the world. “We wanted to create a level playing field” so that someone at a big center with a supercomputer was at no more of an advantage than a postdoc in Scotland with a smaller computer and slower internet link, says Oxford’s Naomi Allen, the project’s chief epidemiologist. They came up with a plan: They gave researchers 3 weeks to download the encrypted files. Then, on 19 July 2017, they released a final encryption key, firing the starting gun for a scientific race.

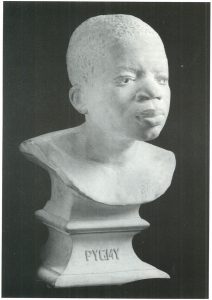

In early 2017, epidemiologist Rory Collins at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and his team faced a test of their principles. They run the UK Biobank (UKB), a huge research project probing the health and genetics of 500,000 British people. They were planning their most sought-after data release yet: genetic profiles for all half-million participants. Three hundred research groups had signed up to download 8 terabytes of data—the equivalent of more than 5000 streamed movies. That’s enough to tie up a home computer for weeks, threatening a key goal of the UKB: to give equal access to any qualified researcher in the world. “We wanted to create a level playing field” so that someone at a big center with a supercomputer was at no more of an advantage than a postdoc in Scotland with a smaller computer and slower internet link, says Oxford’s Naomi Allen, the project’s chief epidemiologist. They came up with a plan: They gave researchers 3 weeks to download the encrypted files. Then, on 19 July 2017, they released a final encryption key, firing the starting gun for a scientific race. In the summer of 1904, Ota Benga was bought in the Congo from slave traders for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. The man who purchased him was an American entrepreneur and explorer named Samuel Phillips Verner. Verner was under contract to bring pygmies for display at the St. Louis World Fair. Later, Verner was awarded a gold medal for his services to the young discipline of anthropology.

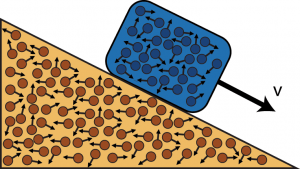

In the summer of 1904, Ota Benga was bought in the Congo from slave traders for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. The man who purchased him was an American entrepreneur and explorer named Samuel Phillips Verner. Verner was under contract to bring pygmies for display at the St. Louis World Fair. Later, Verner was awarded a gold medal for his services to the young discipline of anthropology. One of the hardest things to explain is why complex systems are actually different from simple systems. The problem is rooted in a set of ideas that work together and reinforce each other so that they appear seamless: Given a set of properties that a system has, we can study those properties with experiments and model what those properties do over time. Everything that is needed should be found in the data and the model we write down. The flaw in this seemingly obvious statement is that what is missing is realizing that one may be starting from the wrong properties. One might have missed one of the key properties that we need to include, or the set of properties that one has to describe might change over time. Then why don’t we add more properties until we include enough? The problem is that we will be overwhelmed by too many of them, the process never ends.

One of the hardest things to explain is why complex systems are actually different from simple systems. The problem is rooted in a set of ideas that work together and reinforce each other so that they appear seamless: Given a set of properties that a system has, we can study those properties with experiments and model what those properties do over time. Everything that is needed should be found in the data and the model we write down. The flaw in this seemingly obvious statement is that what is missing is realizing that one may be starting from the wrong properties. One might have missed one of the key properties that we need to include, or the set of properties that one has to describe might change over time. Then why don’t we add more properties until we include enough? The problem is that we will be overwhelmed by too many of them, the process never ends.  In

In