Thomas B. Edsall in the New York Times:

Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the idealistic class of 64 Democratic House freshmen are armed with a reform agenda.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the idealistic class of 64 Democratic House freshmen are armed with a reform agenda.

This includes H.R. 1, a 571-page bill that addresses voting rights, corruption, gerrymandering and campaign finance reform as well as the creation of a Select Committee on the Climate Crisis — a first step toward a “Green New Deal.”

Proponents of this ambitious project face a determined adversary, however — the top ranks of the interest group establishment, skilled in co-opting liberal members of Congress and converting initiatives to square with the interests of corporate America.

The upper stratum of the Washington lobbying community often exercises de facto veto power over the legislative process, dominating congressional policymaking, funneling campaign money to both parties and offering lucrative employment to retiring and defeated members of the House and Senate.

Lobbyists exercise this power across the course of a member’s career. “Whoever is elected is immediately met with a growing lobbying onslaught by the same big players,” write Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at New America, Matt Grossmann, a political scientist at Michigan State and Tim LaPira, a political scientist at James Madison University, who have contributed a chapter to “Can America Govern Itself?” a book edited by Francis Lee and Nolan McCarty that is coming out in June.

More here.

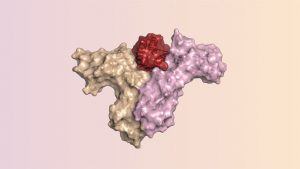

For patients with aggressive kidney and skin cancers, an immune-boosting protein called interleukin-2 (IL-2) can be a lifesaver. But the dose at which it fights cancer can also produce life-threatening side effects. Now, scientists have used computer modeling to design a new protein from scratch that mimics IL-2’s immune-enhancing abilities, while avoiding its dangerous side effects. The protein has so far been tested only in animals, but it may soon enter human trials. IL-2 plays a key role in directing the body’s immune response to outside invaders. The protein, a signaling molecule called a cytokine, ramps up the activity of white blood cells known as T lymphocytes by binding simultaneously to their IL-2β and IL-2γ receptors. In cells where a third type of receptor, IL-2α, is present, IL-2 binds collectively to all three. In other white blood cells, this dampens the body’s immune response. But it can also occur in cells in blood vessels, causing those vessels to leak, a potentially deadly condition.

For patients with aggressive kidney and skin cancers, an immune-boosting protein called interleukin-2 (IL-2) can be a lifesaver. But the dose at which it fights cancer can also produce life-threatening side effects. Now, scientists have used computer modeling to design a new protein from scratch that mimics IL-2’s immune-enhancing abilities, while avoiding its dangerous side effects. The protein has so far been tested only in animals, but it may soon enter human trials. IL-2 plays a key role in directing the body’s immune response to outside invaders. The protein, a signaling molecule called a cytokine, ramps up the activity of white blood cells known as T lymphocytes by binding simultaneously to their IL-2β and IL-2γ receptors. In cells where a third type of receptor, IL-2α, is present, IL-2 binds collectively to all three. In other white blood cells, this dampens the body’s immune response. But it can also occur in cells in blood vessels, causing those vessels to leak, a potentially deadly condition. The testament Dostoevsky left his children was the parable of the Prodigal Son. He asked that it be read to them the night of the day he knew would be his last, and the late, great Joseph Frank judged that Dostoevsky had probably understood the whole of his life and all of his literature as having existed under the sign of this tale of “transgression, forgiveness, and redemption.”

The testament Dostoevsky left his children was the parable of the Prodigal Son. He asked that it be read to them the night of the day he knew would be his last, and the late, great Joseph Frank judged that Dostoevsky had probably understood the whole of his life and all of his literature as having existed under the sign of this tale of “transgression, forgiveness, and redemption.” Donald Trump campaigned on the absurd lie that the United States could construct a large concrete wall across the entire US-Mexico border and coerce the Mexican government into paying for its construction. The government is currently shut down because Trump refuses to admit that his absurd lie was, in fact, an absurd lie.

Donald Trump campaigned on the absurd lie that the United States could construct a large concrete wall across the entire US-Mexico border and coerce the Mexican government into paying for its construction. The government is currently shut down because Trump refuses to admit that his absurd lie was, in fact, an absurd lie. Thomas Piketty and his colleagues

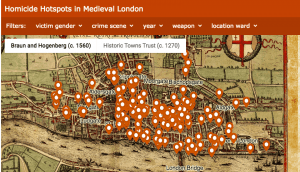

Thomas Piketty and his colleagues In July of 1316, a priest with a hankering for fresh apples sneaked into a walled garden in the Cripplegate area of London to help himself to the fruits therein. The gardener caught him in the act, and the priest brutally stabbed him to death with a knife—hardly godly behavior, but this was the Middle Ages. A religious occupation was no guarantee of moral standing.

In July of 1316, a priest with a hankering for fresh apples sneaked into a walled garden in the Cripplegate area of London to help himself to the fruits therein. The gardener caught him in the act, and the priest brutally stabbed him to death with a knife—hardly godly behavior, but this was the Middle Ages. A religious occupation was no guarantee of moral standing. Forward-thinking companies strive to be socially responsible. Beer commercials exhort us to drink responsibly. And every parent wants their kid to be more responsible. All in all, responsibility is a good thing, right? It is, until it’s not. What to do when you have too much of a good thing? This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen offers four signs of over-responsibility, plus three ways to overcome it. Being a responsible person is usually a good thing—it means you’re committed, dependable, accountable, and care about others. It’s the opposite of shirking responsibility by pointing fingers or making excuses. But it’s easy to go too far. Do you take on everyone’s tasks? If someone you love is grumpy, do you assume it’s something you did? Do you apologize when someone bumps into you? Owning what’s yours—mistakes and blunders included—is a sign of maturity, but owning everybody else’s mistakes and blunders, not to mention tasks, duties, and emotions, is a sign of over-responsibility.

Forward-thinking companies strive to be socially responsible. Beer commercials exhort us to drink responsibly. And every parent wants their kid to be more responsible. All in all, responsibility is a good thing, right? It is, until it’s not. What to do when you have too much of a good thing? This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen offers four signs of over-responsibility, plus three ways to overcome it. Being a responsible person is usually a good thing—it means you’re committed, dependable, accountable, and care about others. It’s the opposite of shirking responsibility by pointing fingers or making excuses. But it’s easy to go too far. Do you take on everyone’s tasks? If someone you love is grumpy, do you assume it’s something you did? Do you apologize when someone bumps into you? Owning what’s yours—mistakes and blunders included—is a sign of maturity, but owning everybody else’s mistakes and blunders, not to mention tasks, duties, and emotions, is a sign of over-responsibility. In the animal world, monogamy has some clear perks. Living in pairs can give animals some stability and certainty in the constant struggle to reproduce and protect their young—which may be why it has evolved independently in various species. Now, an analysis of gene activity within the brains of frogs, rodents, fish, and birds suggests there may be a pattern common to monogamous creatures. Despite very different brain structures and evolutionary histories, these animals all seem to have developed monogamy by turning on and off some of the same sets of genes. “It is quite surprising,” says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Hopi Hoekstra, who was not involved in the new work. “It suggests that there’s a sort of genomic strategy to becoming monogamous that evolution has repeatedly tapped into.” Evolutionary biologists have proposed various

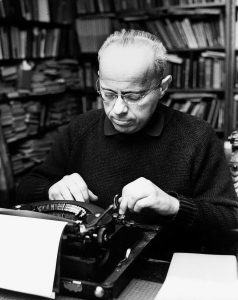

In the animal world, monogamy has some clear perks. Living in pairs can give animals some stability and certainty in the constant struggle to reproduce and protect their young—which may be why it has evolved independently in various species. Now, an analysis of gene activity within the brains of frogs, rodents, fish, and birds suggests there may be a pattern common to monogamous creatures. Despite very different brain structures and evolutionary histories, these animals all seem to have developed monogamy by turning on and off some of the same sets of genes. “It is quite surprising,” says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Hopi Hoekstra, who was not involved in the new work. “It suggests that there’s a sort of genomic strategy to becoming monogamous that evolution has repeatedly tapped into.” Evolutionary biologists have proposed various  The science-fiction writer and futurist Stanisław Lem was well acquainted with the way that fictional worlds can sometimes encroach upon reality. In his autobiographical essay “

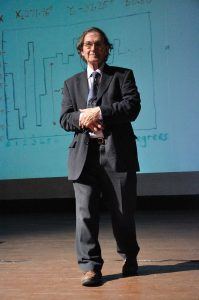

The science-fiction writer and futurist Stanisław Lem was well acquainted with the way that fictional worlds can sometimes encroach upon reality. In his autobiographical essay “ Sir Roger Penrose has had a remarkable life. He has contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of general relativity, perhaps more than anyone since Einstein himself — Penrose diagrams, singularity theorems, the Penrose process, cosmic censorship, and the list goes on. He has made important contributions to mathematics, including such fun ideas as the Penrose triangle and aperiodic tilings. He has also made bold conjectures in the notoriously contentious areas of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness. In his spare time he’s managed to become an extremely successful author, writing such books as The Emperor’s New Mind and The Road to Reality. With far too much that we could have talked about, we decided to concentrate in this discussion on spacetime, black holes, and cosmology, but we made sure to reserve some time to dig into quantum mechanics and the brain by the end.

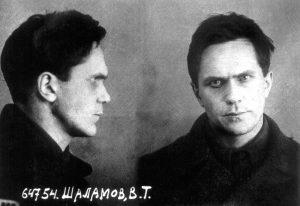

Sir Roger Penrose has had a remarkable life. He has contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of general relativity, perhaps more than anyone since Einstein himself — Penrose diagrams, singularity theorems, the Penrose process, cosmic censorship, and the list goes on. He has made important contributions to mathematics, including such fun ideas as the Penrose triangle and aperiodic tilings. He has also made bold conjectures in the notoriously contentious areas of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness. In his spare time he’s managed to become an extremely successful author, writing such books as The Emperor’s New Mind and The Road to Reality. With far too much that we could have talked about, we decided to concentrate in this discussion on spacetime, black holes, and cosmology, but we made sure to reserve some time to dig into quantum mechanics and the brain by the end. For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been newly translated into English and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything in Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more.

For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been newly translated into English and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything in Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more. My students and I were in the midst of studying Learning from Las Vegas when the news came of Robert Venturi’s death. We had just absorbed an extraordinary lecture tour of his mother’s house, in all its faux–New England simplicity, which harbored so many allusive surprises; now the book, published in 1972, was revealing itself to be a profoundly American source for the cultural-studies movement whose genealogy we had for so long attributed to the Birmingham School. It also turns out to have been one of the underground blasts that signaled the beginning of postmodernism.

My students and I were in the midst of studying Learning from Las Vegas when the news came of Robert Venturi’s death. We had just absorbed an extraordinary lecture tour of his mother’s house, in all its faux–New England simplicity, which harbored so many allusive surprises; now the book, published in 1972, was revealing itself to be a profoundly American source for the cultural-studies movement whose genealogy we had for so long attributed to the Birmingham School. It also turns out to have been one of the underground blasts that signaled the beginning of postmodernism. The grand term ‘intellectual property’ covers a lot of ground: the software that runs our lives, the movies we watch, the songs we listen to. But also the credit-scoring algorithms that determine the contours of our futures, the chemical structure and manufacturing processes for life-saving pharmaceutical drugs, even the golden arches of McDonald’s and terms such as ‘Google’. All are supposedly ‘intellectual property’. We are urged, whether by stern warnings on the packaging of our Blu-ray discs or by sonorous pronouncements from media company CEOs, to cease and desist from making unwanted, illegal or improper uses of such ‘property’, not to be ‘pirates’, to show the proper respect for the rights of those who own these things. But what kind of property is this? And why do we refer to such a menagerie with one inclusive term?

The grand term ‘intellectual property’ covers a lot of ground: the software that runs our lives, the movies we watch, the songs we listen to. But also the credit-scoring algorithms that determine the contours of our futures, the chemical structure and manufacturing processes for life-saving pharmaceutical drugs, even the golden arches of McDonald’s and terms such as ‘Google’. All are supposedly ‘intellectual property’. We are urged, whether by stern warnings on the packaging of our Blu-ray discs or by sonorous pronouncements from media company CEOs, to cease and desist from making unwanted, illegal or improper uses of such ‘property’, not to be ‘pirates’, to show the proper respect for the rights of those who own these things. But what kind of property is this? And why do we refer to such a menagerie with one inclusive term? For all its economic might, Germany’s main centrist parties are

For all its economic might, Germany’s main centrist parties are