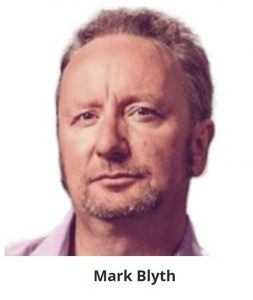

Henning Meyer in Social Europe:

Towards the end of 2018, Henning Meyer, editor-in-chief of Social Europe, spoke to the expert on international political economy Mark Blyth, about the crisis of globalisation, populism, Brexit and other political disasters waiting to happen.

Henning Meyer: Mark Blyth, thank you very much for joining me today to discuss the crisis of globalisation and what political and economic consequences it might have. Let me ask you the first question. Basically, do you think there is a crisis of globalisation? And if there is one, in your opinion, what are its main characteristics?

Mark Blyth: It’s always a tough one. I hate using the word ‘crisis’, because I’ve been doing this stuff for about 30 years now, and when I went to graduate school I read books about crisis. Then we had a crisis. Then we had another crisis. A crisis of this and a crisis of that. There’s a danger that the term becomes meaningless. So I will try and put it in a slightly different cast.

Mark Blyth: It’s always a tough one. I hate using the word ‘crisis’, because I’ve been doing this stuff for about 30 years now, and when I went to graduate school I read books about crisis. Then we had a crisis. Then we had another crisis. A crisis of this and a crisis of that. There’s a danger that the term becomes meaningless. So I will try and put it in a slightly different cast.

Capitalism itself is usually quite a robust system. That is to say, it can not only deal with shocks—it can sometimes benefit from shocks, depending on the type of shock. What’s happened since 2008 is not the type of shocks that you’re robust to, nor do you benefit from. You have a giant real-estate bust, which tends to then accumulate, through the banking sector and the bail-out of the banking sector, into a series of public debt bail-outs, which then leads to greater fragility on that side.

The entire financial sector on the private side, whether it was corporates through corporate debt markets or whether it was consumers through consumer debt, are extremely levered. Wages aren’t growing, which is the real big problem. Inequality has literally never been higher in many cases. And we’re finally waking up to the fact that there’s an environmental crisis that is very, very serious and is going to hit us much sooner than we thought.

More here.

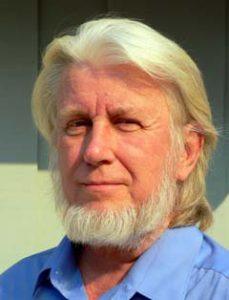

David Ellerman works in disparate fields, from economics and political economy, to social theory and philosophy, to mathematical logic and quantum mechanics. From 1992 to 2003, he worked, at the World Bank, as economic advisor to the Chief Economist (Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern). He has published numerous articles and books, among which The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm (1990), Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy (1992), and Helping People Help Themselves: From the World Bank to an Alternative Philosophy of Development Assistance (2005). He is currently visiting scholar at the University of California, Riverside and the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

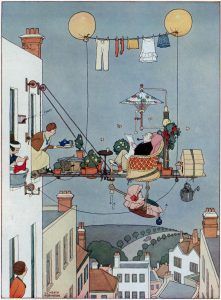

David Ellerman works in disparate fields, from economics and political economy, to social theory and philosophy, to mathematical logic and quantum mechanics. From 1992 to 2003, he worked, at the World Bank, as economic advisor to the Chief Economist (Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern). He has published numerous articles and books, among which The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm (1990), Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy (1992), and Helping People Help Themselves: From the World Bank to an Alternative Philosophy of Development Assistance (2005). He is currently visiting scholar at the University of California, Riverside and the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. It’s one thing for an artist to establish a reputation, another for them to enter the dictionary. When the British want to describe a whimsical, improvised or over-elaborate mechanism, they call it a “Heath Robinson” machine, after the drawings of William Heath Robinson. (Americans have a direct equivalent in Rube Goldberg, whose creations, inspired by similar rapid changes in society and technology, are remarkably similar to those of his British counterpart.) A new exhibition of Heath Robinson’s work shows how he became a household name, in more ways than one.

It’s one thing for an artist to establish a reputation, another for them to enter the dictionary. When the British want to describe a whimsical, improvised or over-elaborate mechanism, they call it a “Heath Robinson” machine, after the drawings of William Heath Robinson. (Americans have a direct equivalent in Rube Goldberg, whose creations, inspired by similar rapid changes in society and technology, are remarkably similar to those of his British counterpart.) A new exhibition of Heath Robinson’s work shows how he became a household name, in more ways than one. A male flame bowerbird is a creature of incandescent beauty. The hue of his plumage transitions seamlessly from molten red to sunshine yellow. But that radiance is not enough to attract a mate. When males of most bowerbird species are ready to begin courting, they set about building the structure for which they are named: an assemblage of twigs shaped into a spire, corridor or hut. They decorate their bowers with scores of colorful objects, like flowers, berries, snail shells or, if they are near an urban area, bottle caps and plastic cutlery. Some bowerbirds even arrange the items in their collection from smallest to largest, forming a walkway that makes themselves and their trinkets all the more striking to a female — an optical illusion known as forced perspective that humans did not perfect until the 15th century. Yet even this remarkable exhibition is not sufficient to satisfy a female flame bowerbird. Should a female show initial interest, the male must react immediately. Staring at the female, his pupils swelling and shrinking like a heartbeat, he begins a dance best described as psychotically sultry. He bobs, flutters, puffs his chest. He crouches low and rises slowly, brandishing one wing in front of his head like a magician’s cape. Suddenly his whole body convulses like a windup alarm clock. If the female approves, she will copulate with him for two or three seconds. They will never meet again.

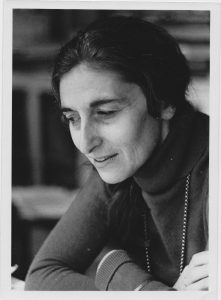

A male flame bowerbird is a creature of incandescent beauty. The hue of his plumage transitions seamlessly from molten red to sunshine yellow. But that radiance is not enough to attract a mate. When males of most bowerbird species are ready to begin courting, they set about building the structure for which they are named: an assemblage of twigs shaped into a spire, corridor or hut. They decorate their bowers with scores of colorful objects, like flowers, berries, snail shells or, if they are near an urban area, bottle caps and plastic cutlery. Some bowerbirds even arrange the items in their collection from smallest to largest, forming a walkway that makes themselves and their trinkets all the more striking to a female — an optical illusion known as forced perspective that humans did not perfect until the 15th century. Yet even this remarkable exhibition is not sufficient to satisfy a female flame bowerbird. Should a female show initial interest, the male must react immediately. Staring at the female, his pupils swelling and shrinking like a heartbeat, he begins a dance best described as psychotically sultry. He bobs, flutters, puffs his chest. He crouches low and rises slowly, brandishing one wing in front of his head like a magician’s cape. Suddenly his whole body convulses like a windup alarm clock. If the female approves, she will copulate with him for two or three seconds. They will never meet again. Perhaps no author has made more art of dispossession than Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The author of a dozen novels and twice as many screenplays — she’s the only person to have won both the Booker Prize (for her eighth and best-known novel, “Heat and Dust”) and an Academy Award (twice, for best adapted screenplay) — Jhabvala was 12 when she fled Nazi Germany with her family in 1939. After the war, when her father learned the fate of the relatives left behind, he killed himself.

Perhaps no author has made more art of dispossession than Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The author of a dozen novels and twice as many screenplays — she’s the only person to have won both the Booker Prize (for her eighth and best-known novel, “Heat and Dust”) and an Academy Award (twice, for best adapted screenplay) — Jhabvala was 12 when she fled Nazi Germany with her family in 1939. After the war, when her father learned the fate of the relatives left behind, he killed himself.

“We are in considerable doubt that you will develop into our professional stereotype of what an experimental psychologist should be.” When the Harvard psychology department kicked Judith Rich Harris out of their PhD program in 1960, they could not have known how true the words in their expulsion letter would turn out to be.

“We are in considerable doubt that you will develop into our professional stereotype of what an experimental psychologist should be.” When the Harvard psychology department kicked Judith Rich Harris out of their PhD program in 1960, they could not have known how true the words in their expulsion letter would turn out to be.

When

When  Having read his book carefully, I believe it’s crucially important to take Pinker to task for some dangerously erroneous arguments he makes. Pinker is, after all, an intellectual darling of the most powerful echelons of global society. He

Having read his book carefully, I believe it’s crucially important to take Pinker to task for some dangerously erroneous arguments he makes. Pinker is, after all, an intellectual darling of the most powerful echelons of global society. He  Issuing a clarion call against the Modi government, an estimated 200 million workers across various sectors successfully carried out a

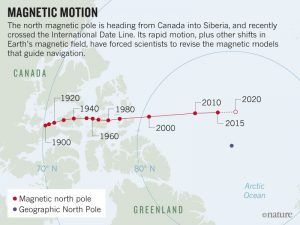

Issuing a clarion call against the Modi government, an estimated 200 million workers across various sectors successfully carried out a  Something strange is going on at the top of the world. Earth’s north magnetic pole has been skittering away from Canada and towards Siberia, driven by liquid iron sloshing within the planet’s core. The magnetic pole is moving so quickly that it has forced the world’s geomagnetism experts into a rare move. On 15 January, they are set to update the World Magnetic Model, which describes

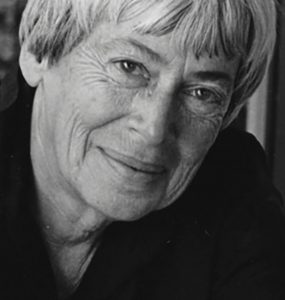

Something strange is going on at the top of the world. Earth’s north magnetic pole has been skittering away from Canada and towards Siberia, driven by liquid iron sloshing within the planet’s core. The magnetic pole is moving so quickly that it has forced the world’s geomagnetism experts into a rare move. On 15 January, they are set to update the World Magnetic Model, which describes  In 1987, my first year in college, I happened upon a notice outside of the English department for a winter session opportunity: escorting a visiting artist during a week-long interdisciplinary conference held at my school, the University of Rochester. I ran my finger down the list of artists’ names until it stopped on one: Ursula K. Le Guin.

In 1987, my first year in college, I happened upon a notice outside of the English department for a winter session opportunity: escorting a visiting artist during a week-long interdisciplinary conference held at my school, the University of Rochester. I ran my finger down the list of artists’ names until it stopped on one: Ursula K. Le Guin. In recent years many prominent people have expressed worries about artificial intelligence (AI). Elon Musk thinks it’s the “

In recent years many prominent people have expressed worries about artificial intelligence (AI). Elon Musk thinks it’s the “ Iraq has endured decades of sanctions, war, invasion, regime change and dysfunctional government. These span Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, a devastating eight-year war with Iran in the 1980s and crippling UN sanctions throughout the 1990s. Those difficult years gave way to the traumas of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and its chaotic aftermath, which brought the insurgents of the Islamic State to the outskirts of the Iraqi capital Baghdad in 2014.

Iraq has endured decades of sanctions, war, invasion, regime change and dysfunctional government. These span Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, a devastating eight-year war with Iran in the 1980s and crippling UN sanctions throughout the 1990s. Those difficult years gave way to the traumas of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and its chaotic aftermath, which brought the insurgents of the Islamic State to the outskirts of the Iraqi capital Baghdad in 2014. Few issues in economics have generated such heated debates as the nature of money and its role in the economy. What is money? How is it related to debt? How does it influence economic activity? The recent mainstream economic literature is an unfortunate exception. Bar a few who have sailed into these waters, money has been allowed to sink by the macroeconomics profession. And with little or no regrets.

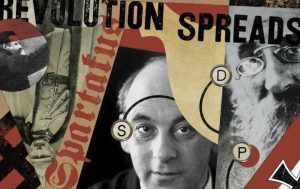

Few issues in economics have generated such heated debates as the nature of money and its role in the economy. What is money? How is it related to debt? How does it influence economic activity? The recent mainstream economic literature is an unfortunate exception. Bar a few who have sailed into these waters, money has been allowed to sink by the macroeconomics profession. And with little or no regrets. It was slightly more than a century ago, in November 1918, that revolution swept through Germany, bringing chaos to a country that, in the final days of World War I, was already in desperate straits and verging on collapse. Although it was obvious to nearly everyone that the war was lost, the fighting staggered on, even as a growing pacifist movement issued the cry for “Peace, Freedom, Bread!” In Kiel on the Baltic Sea, sailors at the docks refused the order for a last battle and went into open mutiny, while soldiers and revolutionary workers in Berlin called for a general strike. Kaiser Wilhelm II, an absurd and incompetent militarist, at last faced the truth that his time was up and abdicated the throne, leaving confusion in his wake. On November 9, Philipp Scheidemann, a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP), seized the moment to declare the founding of a new republic.

It was slightly more than a century ago, in November 1918, that revolution swept through Germany, bringing chaos to a country that, in the final days of World War I, was already in desperate straits and verging on collapse. Although it was obvious to nearly everyone that the war was lost, the fighting staggered on, even as a growing pacifist movement issued the cry for “Peace, Freedom, Bread!” In Kiel on the Baltic Sea, sailors at the docks refused the order for a last battle and went into open mutiny, while soldiers and revolutionary workers in Berlin called for a general strike. Kaiser Wilhelm II, an absurd and incompetent militarist, at last faced the truth that his time was up and abdicated the throne, leaving confusion in his wake. On November 9, Philipp Scheidemann, a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP), seized the moment to declare the founding of a new republic.