by Abigail Akavia

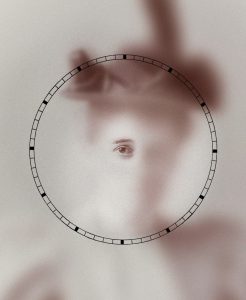

A group of young women performing exercises at the ballet barre and an angry mob chanting “lock her up.” These two situations, where the exact same action is performed by a group of people, may have more in common than it appears at first. Kinesthetic empathy, a recent topic of research for neurobiologists, dance theorists and a range of scholars and professionals in between, offers an interesting perspective on this issue, since it points to the emotional effect of physical activities carried out in group settings.

Empathy is a blanket term for a wide range of interpersonal phenomena: it is probably most commonly understood as an other-oriented feeling of concern or compassion. Empathy can also be defined as an ability to imagine what the other person is going through, or as an intuitive understanding of another person, including an understanding that is more physical than mental. Mirror neurons in the brain—for example, those firing both when we itch our foot and when we see someone else itching their foot—are probably involved in such a body-mediated and body-motivated awareness of the other.

It is remarkable that we can also feel empathy towards a fictional character, say in a book, a film, or in the theater. The latter situation is especially interesting because by understanding how audience members relate emotionally to what they see onstage we may gain access to how the audience as a gathering of disparate individuals becomes a group, a collective whose emotions and reactions can be manipulated and controlled. When the aesthetic medium is dance, the nexus of emotional reactions and physical experience is more obvious, even if not easier to parse; for it is through the body and without the mediation of words that we are “moved.” Read more »

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time. Nick McDonell has spent the past decade going in and out of war zones across the

Nick McDonell has spent the past decade going in and out of war zones across the  Not long ago, during an Amtrak ride, I met a college student who told me he was a fiction writer. I asked him what he’d been writing and reading, and he said that he was writing a novel about time travel, and that he was reading — well, he had been reading Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth,” but after about 50 pages, he said, he’d tossed it into the trash.

Not long ago, during an Amtrak ride, I met a college student who told me he was a fiction writer. I asked him what he’d been writing and reading, and he said that he was writing a novel about time travel, and that he was reading — well, he had been reading Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth,” but after about 50 pages, he said, he’d tossed it into the trash. During the twentieth century, discoveries in mathematical logic revolutionized our understanding of the very foundations of mathematics. In 1931, the logician Kurt Gödel showed that, in any system of axioms that is expressive enough to model arithmetic, some true statements will be unprovable

During the twentieth century, discoveries in mathematical logic revolutionized our understanding of the very foundations of mathematics. In 1931, the logician Kurt Gödel showed that, in any system of axioms that is expressive enough to model arithmetic, some true statements will be unprovable On “60 Minutes” Sunday, Ocasio-Cortez talked about a 70 percent tax rate for Americans earning more than $10 million a year. She said this would fund a Green New Deal: big money for renewable energy and technologies to avert climate catastrophe.

On “60 Minutes” Sunday, Ocasio-Cortez talked about a 70 percent tax rate for Americans earning more than $10 million a year. She said this would fund a Green New Deal: big money for renewable energy and technologies to avert climate catastrophe. Hope is being privatized. Throughout the world, but especially in the United States and the United Kingdom, a seismic shift is underway, displacing aspirations and responsibilities from the larger society to our own individual universes. The detaching of personal expectations from the wider world transforms both.

Hope is being privatized. Throughout the world, but especially in the United States and the United Kingdom, a seismic shift is underway, displacing aspirations and responsibilities from the larger society to our own individual universes. The detaching of personal expectations from the wider world transforms both. Don’t start with a moral theory, start with where you actually are. Here is a question that I think ethicists should be asking alongside Nagel’s famous question about bats (at the moment I want to use it as the title of Epiphanies Chapter 4): “What is it like to be a human being?” So start with that. Start with what it’s like to be you, with your subjectivity here and now, with what looks serious and real and important and beautiful and (yes, why not?) fun to you just as you are, from your own viewpoint. Because actually that’s the only place you ever can start from, really, and one tendency of systematising theories is to obscure this truth.

Don’t start with a moral theory, start with where you actually are. Here is a question that I think ethicists should be asking alongside Nagel’s famous question about bats (at the moment I want to use it as the title of Epiphanies Chapter 4): “What is it like to be a human being?” So start with that. Start with what it’s like to be you, with your subjectivity here and now, with what looks serious and real and important and beautiful and (yes, why not?) fun to you just as you are, from your own viewpoint. Because actually that’s the only place you ever can start from, really, and one tendency of systematising theories is to obscure this truth. Talking about the public role of intellectuals in today’s world, and more specifically in India, is of great significance given changes taking place in culture and politics. It is not simply enough to talk about the role of Indian public intellectuals in the making and preserving of critical mindedness and democratic engagement in Indian academia. One should also pay attention to the role which could and should be played by public intellectuals in promoting moral and political excellence and civic friendship among the future generation of Indians.

Talking about the public role of intellectuals in today’s world, and more specifically in India, is of great significance given changes taking place in culture and politics. It is not simply enough to talk about the role of Indian public intellectuals in the making and preserving of critical mindedness and democratic engagement in Indian academia. One should also pay attention to the role which could and should be played by public intellectuals in promoting moral and political excellence and civic friendship among the future generation of Indians. You slide the key into the door and hear a clunk as the tumblers engage. You rotate the key, twist the doorknob and walk inside. The house is familiar, but the contents foreign. At your left, there’s a map of Minnesota, dangling precariously from the wall. You’re certain it wasn’t there this morning. Below it, you find a plush M&M candy. To the right, a dog, a shiba inu you’ve never seen before. In its mouth, a pair of your expensive socks.

You slide the key into the door and hear a clunk as the tumblers engage. You rotate the key, twist the doorknob and walk inside. The house is familiar, but the contents foreign. At your left, there’s a map of Minnesota, dangling precariously from the wall. You’re certain it wasn’t there this morning. Below it, you find a plush M&M candy. To the right, a dog, a shiba inu you’ve never seen before. In its mouth, a pair of your expensive socks. In his new book, The Origins of Dislike, Amit Chaudhuri unwraps several aspects of reading, writing, publishing, criticism, and thinking in general, mostly to dismantle the perceived virtuosity of these phenomena.

In his new book, The Origins of Dislike, Amit Chaudhuri unwraps several aspects of reading, writing, publishing, criticism, and thinking in general, mostly to dismantle the perceived virtuosity of these phenomena. This week, the American Psychological Association, the country’s largest professional organization of psychologists, did something for men that it’s done for many other demographic groups in the past: It introduced

This week, the American Psychological Association, the country’s largest professional organization of psychologists, did something for men that it’s done for many other demographic groups in the past: It introduced  There is, many believe, a specter haunting the Euro-American world. It is not, as Marx and Engels once exulted, the specter of communism. Nor is it the specter of fascism, though some, including former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, have warned of this. Rather, it is the specter of what journalists, scholars, and other political observers now routinely call “populism.” To be sure, there are few, if any, self-described populist movements afoot: no “populist” parties seeking to mobilize voters and constituencies, no “populist international” attempting to harness discontent as it spreads across national borders. Nor is there any “populist” language, sustained “populist” critique of the status quo, or “populist” platform as there once was in the United States at the very end of the 19th century.

There is, many believe, a specter haunting the Euro-American world. It is not, as Marx and Engels once exulted, the specter of communism. Nor is it the specter of fascism, though some, including former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, have warned of this. Rather, it is the specter of what journalists, scholars, and other political observers now routinely call “populism.” To be sure, there are few, if any, self-described populist movements afoot: no “populist” parties seeking to mobilize voters and constituencies, no “populist international” attempting to harness discontent as it spreads across national borders. Nor is there any “populist” language, sustained “populist” critique of the status quo, or “populist” platform as there once was in the United States at the very end of the 19th century. SINCE ITS FOUNDING in the early 20th century, the U.S. Border Patrol has operated with near-complete impunity, arguably serving as the most politicized and abusive branch of federal law enforcement — even more so than the FBI during J. Edgar Hoover’s directorship.

SINCE ITS FOUNDING in the early 20th century, the U.S. Border Patrol has operated with near-complete impunity, arguably serving as the most politicized and abusive branch of federal law enforcement — even more so than the FBI during J. Edgar Hoover’s directorship.