Jordana Cepelewicz in Quanta:

We humans have always experienced an odd — and oddly deep — connection between the mental worlds and physical worlds we inhabit, especially when it comes to memory. We’re good at remembering landmarks and settings, and if we give our memories a location for context, hanging on to them becomes easier. To remember long speeches, ancient Greek and Roman orators imagined wandering through “memory palaces” full of reminders. Modern memory contest champions still use that technique to “place” long lists of numbers, names and other pieces of information.

We humans have always experienced an odd — and oddly deep — connection between the mental worlds and physical worlds we inhabit, especially when it comes to memory. We’re good at remembering landmarks and settings, and if we give our memories a location for context, hanging on to them becomes easier. To remember long speeches, ancient Greek and Roman orators imagined wandering through “memory palaces” full of reminders. Modern memory contest champions still use that technique to “place” long lists of numbers, names and other pieces of information.

As the philosopher Immanuel Kant put it, the concept of space serves as the organizing principle by which we perceive and interpret the world, even in abstract ways. “Our language is riddled with spatial metaphors for reasoning, and for memory in general,” said Kim Stachenfeld, a neuroscientist at the British artificial intelligence company DeepMind.

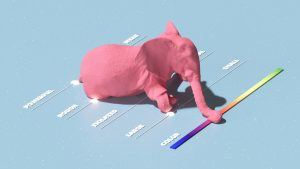

In the past few decades, research has shown that for at least two of our faculties, memory and navigation, those metaphors may have a physical basis in the brain. A small seahorse-shaped structure, the hippocampus, is essential to both those functions, and evidence has started to suggest that the same coding scheme — a grid-based form of representation — may underlie them. Recent insights have prompted some researchers to propose that this same coding scheme can help us navigate other kinds of information, including sights, sounds and abstract concepts. The most ambitious suggestions even venture that these grid codes could be the key to understanding how the brain processes all details of general knowledge, perception and memory.

More here.