Katy Lederer at n+1:

Like all honest ethnographies, Carbon Ideologies also functions as an intellectual autobiography. We learn that, during his six years of research, Vollmann depleted his original advance and then spent his own money and unnamed others’ to “hike up strip-mined mountains, sniff crude oil, and occasionally tan my face with gamma rays.” (He relegates renewables to just a few pages, largely dismissing them, as he explicitly does solar, as “an ideology of hope—not my department.”) He loves gadgets and toys. In the first volume, this love expresses itself mainly in the form of an unmistakably phallic pancake frisker he carries around Fukushima, which he uses to measure the radioactivity of everything from roadside vegetation to the ubiquitous black bags of nuclear waste that line the empty streets. Dozens of pictures serve to document his travels. In one we see Vollmann’s hand grasping the frisker at the neck, pointing it at a bald statue of a praying man at a temple called Hen Jo.

Like all honest ethnographies, Carbon Ideologies also functions as an intellectual autobiography. We learn that, during his six years of research, Vollmann depleted his original advance and then spent his own money and unnamed others’ to “hike up strip-mined mountains, sniff crude oil, and occasionally tan my face with gamma rays.” (He relegates renewables to just a few pages, largely dismissing them, as he explicitly does solar, as “an ideology of hope—not my department.”) He loves gadgets and toys. In the first volume, this love expresses itself mainly in the form of an unmistakably phallic pancake frisker he carries around Fukushima, which he uses to measure the radioactivity of everything from roadside vegetation to the ubiquitous black bags of nuclear waste that line the empty streets. Dozens of pictures serve to document his travels. In one we see Vollmann’s hand grasping the frisker at the neck, pointing it at a bald statue of a praying man at a temple called Hen Jo.

more here.

The question of who owns Kafka is at the heart of Benjamin Balint’s thought-provoking and assiduously researched Kafka’s Last Trial, which (to simplify) is about the attempt by the state of Israel to prevent the sale of Kafka’s manuscripts from a private collection there to anywhere overseas, particularly to the German Literature Archive in Marbach. Spoiler alert for those who were not reading the newspapers in 2016: the state won. But Balint’s book is not so much about the outcome as it is about the arguments that were brought forward.

The question of who owns Kafka is at the heart of Benjamin Balint’s thought-provoking and assiduously researched Kafka’s Last Trial, which (to simplify) is about the attempt by the state of Israel to prevent the sale of Kafka’s manuscripts from a private collection there to anywhere overseas, particularly to the German Literature Archive in Marbach. Spoiler alert for those who were not reading the newspapers in 2016: the state won. But Balint’s book is not so much about the outcome as it is about the arguments that were brought forward. For his eighth birthday, Richard Hull’s mother bought him a Geiger counter. It was 1955 and the United States was testing nuclear weapons on its own soil. “They would always announce a test in the newspaper,” Hull remembers. “The material that went into the stratosphere drifted with the prevailing winds. The radioactive fallout particles came down with rain, as far north as New York and as far south as Georgia.” Hull lived then, as now, in Virginia, squarely in the path of the fallout that blew east from the bombs in the Nevada desert. “We would have days when we couldn’t have milk,” he remembers, “because of the strontium-90.” Hull wanted a Geiger counter not because he was afraid of radioactivity, but because he was enthralled by it. He pointed his new toy at anything that might make it tick, from wristwatches to rocks, and he collected fallout from the bombs. “I would take bird-bath water, or water that I gathered in pails from the downspouts of the house, and I would slowly evaporate that water on my mother’s stove, and that would leave the solids behind. And they were highly radioactive,” he says, with evident satisfaction.

For his eighth birthday, Richard Hull’s mother bought him a Geiger counter. It was 1955 and the United States was testing nuclear weapons on its own soil. “They would always announce a test in the newspaper,” Hull remembers. “The material that went into the stratosphere drifted with the prevailing winds. The radioactive fallout particles came down with rain, as far north as New York and as far south as Georgia.” Hull lived then, as now, in Virginia, squarely in the path of the fallout that blew east from the bombs in the Nevada desert. “We would have days when we couldn’t have milk,” he remembers, “because of the strontium-90.” Hull wanted a Geiger counter not because he was afraid of radioactivity, but because he was enthralled by it. He pointed his new toy at anything that might make it tick, from wristwatches to rocks, and he collected fallout from the bombs. “I would take bird-bath water, or water that I gathered in pails from the downspouts of the house, and I would slowly evaporate that water on my mother’s stove, and that would leave the solids behind. And they were highly radioactive,” he says, with evident satisfaction. Doctors are not accustomed to making medication choices using genetics. What they have done, for decades, is to look at easily observed factors such as a patient’s age and weight and kidney or liver functions. They also considered what other medications a patient is taking and any personal preferences.

Doctors are not accustomed to making medication choices using genetics. What they have done, for decades, is to look at easily observed factors such as a patient’s age and weight and kidney or liver functions. They also considered what other medications a patient is taking and any personal preferences.  Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea. In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love. Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it.

Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it. Edward Said’s

Edward Said’s  When I was seven, my parents bought me and my brother an Atari 2600, the first mass game console. The game it came with was “Asteroids.” We played that game an awful lot. One night, we snuck down in the middle of the night only to discover my Dad already playing.

When I was seven, my parents bought me and my brother an Atari 2600, the first mass game console. The game it came with was “Asteroids.” We played that game an awful lot. One night, we snuck down in the middle of the night only to discover my Dad already playing. Thomas Piketty, the French economist whose 2013 bestseller

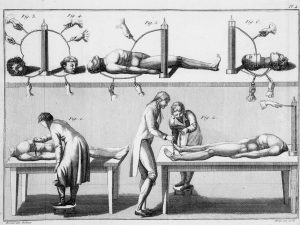

Thomas Piketty, the French economist whose 2013 bestseller  On 17 January 1803, a young man named George Forster was hanged for murder at Newgate prison in London. After his execution, as often happened, his body was carried ceremoniously across the city to the Royal College of Surgeons, where it would be publicly dissected. What actually happened was rather more shocking than simple dissection though. Forster was going to be electrified. The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “animal electricity” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the slab before him, Aldini and his assistants started to experiment. The Timesnewspaper reported: “On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.”

On 17 January 1803, a young man named George Forster was hanged for murder at Newgate prison in London. After his execution, as often happened, his body was carried ceremoniously across the city to the Royal College of Surgeons, where it would be publicly dissected. What actually happened was rather more shocking than simple dissection though. Forster was going to be electrified. The experiments were to be carried out by the Italian natural philosopher Giovanni Aldini, the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who discovered “animal electricity” in 1780, and for whom the field of galvanism is named. With Forster on the slab before him, Aldini and his assistants started to experiment. The Timesnewspaper reported: “On the first application of the process to the face, the jaw of the deceased criminal began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process, the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.”