Larry Arnhart in The New Atlantis:

In the first issue of The New Atlantis, Leon Kass suggests that if biotechnology were to transform human nature, it would do so to satisfy the human dream of physical and mental perfection — “ageless bodies, happy souls.” But how likely is that? As an indication of what he foresees, Kass says that with drugs, “we can eliminate psychic distress, we can produce states of transient euphoria, and we can engineer more permanent conditions of good cheer, optimism, and contentment.” He refers to those “powerful yet seemingly safe anti-depressant and mood brighteners like Prozac, capable in some people of utterly changing their outlook on life from that of Eeyore to that of Mary Poppins.” Similarly, psychiatrist Peter Kramer — in his best-selling book Listening to Prozac — described patients using Prozac who were not just cured of depression but so transformed in their personalities as to be “better than well.” Shy, quiet people were apparently turned into ebullient and socially engaging people. “Like Garrison Keillor’s marvelous Powdermilk biscuits,” Kramer observed, “Prozac gives these patients the courage to do what needs to be done.” This was the beginning, he concluded, of “cosmetic psychopharmacology,” by which people could use chemicals to take on whatever personality they might prefer.

In the first issue of The New Atlantis, Leon Kass suggests that if biotechnology were to transform human nature, it would do so to satisfy the human dream of physical and mental perfection — “ageless bodies, happy souls.” But how likely is that? As an indication of what he foresees, Kass says that with drugs, “we can eliminate psychic distress, we can produce states of transient euphoria, and we can engineer more permanent conditions of good cheer, optimism, and contentment.” He refers to those “powerful yet seemingly safe anti-depressant and mood brighteners like Prozac, capable in some people of utterly changing their outlook on life from that of Eeyore to that of Mary Poppins.” Similarly, psychiatrist Peter Kramer — in his best-selling book Listening to Prozac — described patients using Prozac who were not just cured of depression but so transformed in their personalities as to be “better than well.” Shy, quiet people were apparently turned into ebullient and socially engaging people. “Like Garrison Keillor’s marvelous Powdermilk biscuits,” Kramer observed, “Prozac gives these patients the courage to do what needs to be done.” This was the beginning, he concluded, of “cosmetic psychopharmacology,” by which people could use chemicals to take on whatever personality they might prefer.

But as even Kramer has conceded, this chemical transformation in personality appears to work well in only a minority of the people taking Prozac. And in recent years, there have been increasing reports of many harmful side effects. This is to be expected, because like all psychotropic drugs, Prozac disrupts the normal functioning of the brain, and the brain responds by countering the effect of the drug, which then induces harmful distortions in the neural system. Specifically, Prozac blocks the normal removal of the neurotransmitter serotonin from the space between nerve cells. This creates an overabundance of serotonin, and the brain responds either by reducing receptivity to serotonin or by reducing the production of serotonin. As a result, the brain creates an imbalance in response to the disruption of the drug and cannot function normally. There is also growing evidence that Prozac does not really cure depression. Many studies have shown that the antidepressant effects of taking Prozac are not much greater than what occurs when people take a placebo pill.

But the most fundamental problem with Prozac is one that it shares with all psychotropic drugs (including old-fashioned ones like alcohol). Emotional suffering is a capacity of human nature shaped by evolutionary history for an adaptive purpose. Emotional suffering is almost always a signal that something is wrong in our lives. It alerts us that there is some problem either in our internal lives, in our social relationships, or in our external circumstances. A psychotropic drug does not help us to understand or solve the problem. Rather, the drug deadens the emotional response of our brain without changing the problem that provoked the emotional response in the first place. When we feel bad because of a problem in our lives, taking a psychotropic drug to make us feel better is evasive and self-defeating.

More here. (Note: From the Summer 2003 issue)

This is a novel about double-dealing, about honourable and dishonourable forms of duplicity, about multiple impersonations, about lies and secrets and their ultimate consequences. Juliet is soon provided with an alternative identity ‑ Iris Carter-Jenkins is her bogus name ‑ and sent to infiltrate a fascist organisation known as the Right Club. This club holds its meetings in a flat above a cafe in South Kensington called the Russian Tea Rooms, which is run by an Admiral Wolkoff and his daughter Anna. The young transcriber has been upgraded to a full-blown MI5 agent, and adopts a mettlesome personality to go with her new role. “She had already decided that Iris Carter-Jenkins was a gutsy kind of girl.” Gutsy enough to carry a small gun in her handbag, and keep her nerve in the face of imminent unmasking.

This is a novel about double-dealing, about honourable and dishonourable forms of duplicity, about multiple impersonations, about lies and secrets and their ultimate consequences. Juliet is soon provided with an alternative identity ‑ Iris Carter-Jenkins is her bogus name ‑ and sent to infiltrate a fascist organisation known as the Right Club. This club holds its meetings in a flat above a cafe in South Kensington called the Russian Tea Rooms, which is run by an Admiral Wolkoff and his daughter Anna. The young transcriber has been upgraded to a full-blown MI5 agent, and adopts a mettlesome personality to go with her new role. “She had already decided that Iris Carter-Jenkins was a gutsy kind of girl.” Gutsy enough to carry a small gun in her handbag, and keep her nerve in the face of imminent unmasking. I first saw an Akomfrah film before I knew it was an Akomfrah film. I remember watching the documentary Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993) in my single dorm room at the top of a hill on McGill’s campus in Montreal. I was alone in college, surrounded by people, and had settled into a life of solemnity. My first laptop had a disc drive, and I had gotten into the habit of borrowing DVDs from the university library in a forlorn attempt to stay in at least one night on the weekends. I, like my father, had gone through a phase contemplating conversion to Islam. Converting from what, I never knew. I didn’t take it as seriously as he did (I never went to mosque), and mostly I just crushed on the hero, who I referred to in the margins of his autobiography as “Mal.” (Unlike my entrepreneurial Jamaican father, I had confused wanting to be a black Muslim with wanting to be a black Marxist.)

I first saw an Akomfrah film before I knew it was an Akomfrah film. I remember watching the documentary Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993) in my single dorm room at the top of a hill on McGill’s campus in Montreal. I was alone in college, surrounded by people, and had settled into a life of solemnity. My first laptop had a disc drive, and I had gotten into the habit of borrowing DVDs from the university library in a forlorn attempt to stay in at least one night on the weekends. I, like my father, had gone through a phase contemplating conversion to Islam. Converting from what, I never knew. I didn’t take it as seriously as he did (I never went to mosque), and mostly I just crushed on the hero, who I referred to in the margins of his autobiography as “Mal.” (Unlike my entrepreneurial Jamaican father, I had confused wanting to be a black Muslim with wanting to be a black Marxist.) The story of energy metabolism—the basic engine of life at the cellular level—is one of electrons flowing much like water flows from mountains to the sea. Our cells can make use of this flow by regulating how these electrons travel, and by harvesting energy from them as they do so. The whole set-up is really not so unlike a hydroelectric dam. The sea toward which these electrons flow is oxygen, and for most of life on earth, iron is the river. (Octopuses are strange outliers here—they use copper instead of iron, which makes their blood greenish-blue rather than red). Oxygen is hungry for electrons, making it an ideal destination. The proteins that facilitate the delivery contain tiny cores of iron, which manage the handling of the electrons as they are shuttled toward oxygen.

The story of energy metabolism—the basic engine of life at the cellular level—is one of electrons flowing much like water flows from mountains to the sea. Our cells can make use of this flow by regulating how these electrons travel, and by harvesting energy from them as they do so. The whole set-up is really not so unlike a hydroelectric dam. The sea toward which these electrons flow is oxygen, and for most of life on earth, iron is the river. (Octopuses are strange outliers here—they use copper instead of iron, which makes their blood greenish-blue rather than red). Oxygen is hungry for electrons, making it an ideal destination. The proteins that facilitate the delivery contain tiny cores of iron, which manage the handling of the electrons as they are shuttled toward oxygen. In the

In the  Decades before the rise of social media, polarisation plagued discussions about language. By and large, it still does. Everyone who cares about the topic is officially required to take one of two stances. Either you smugly preen about the mistakes you find abhorrent – this makes you a so-called prescriptivist – or you show off your knowledge of language change, and poke holes in the prescriptivists’ facts – this makes you a descriptivist. Group membership is mandatory, and the two are mutually exclusive.

Decades before the rise of social media, polarisation plagued discussions about language. By and large, it still does. Everyone who cares about the topic is officially required to take one of two stances. Either you smugly preen about the mistakes you find abhorrent – this makes you a so-called prescriptivist – or you show off your knowledge of language change, and poke holes in the prescriptivists’ facts – this makes you a descriptivist. Group membership is mandatory, and the two are mutually exclusive. The concept of

The concept of

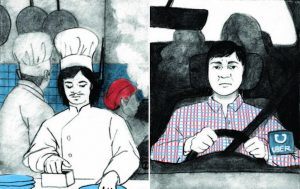

It goes without saying — everyone knows it now, even if they can’t say why — that things like social media are bad for us, that many of us are clinically addicted to our phones, that life online brings out the worst in many, and probably in most of us. Twitter has damaged our national discourse, infecting it with a hair-triggered, toxic factionalism. The news is familiar enough — someone says something, Twitter erupts with outrage; details to follow. This is news. We treat all this with a knowing grimace, and write wry little tweets about how Twitter is toxic. We admire the founders of websites and apps that make us miserable, and if we are ambitious entrepreneurial types, aspire to be like them.

It goes without saying — everyone knows it now, even if they can’t say why — that things like social media are bad for us, that many of us are clinically addicted to our phones, that life online brings out the worst in many, and probably in most of us. Twitter has damaged our national discourse, infecting it with a hair-triggered, toxic factionalism. The news is familiar enough — someone says something, Twitter erupts with outrage; details to follow. This is news. We treat all this with a knowing grimace, and write wry little tweets about how Twitter is toxic. We admire the founders of websites and apps that make us miserable, and if we are ambitious entrepreneurial types, aspire to be like them. Hypnopaedia aka Sleep Learning had been thrust upon the public in 1921, courtesy of a Science and Invention Magazine cover story. Echoing Poe, Hugo Gernsback informed his readers that sleep “is only another form of death,” but our subconscious “is always on the alert.” If we could “superimpose” learning on our sleeping senses, would it not be “an inestimable boon to humanity?” Would it not “lift the entire human race to a truly unimaginable extent?”

Hypnopaedia aka Sleep Learning had been thrust upon the public in 1921, courtesy of a Science and Invention Magazine cover story. Echoing Poe, Hugo Gernsback informed his readers that sleep “is only another form of death,” but our subconscious “is always on the alert.” If we could “superimpose” learning on our sleeping senses, would it not be “an inestimable boon to humanity?” Would it not “lift the entire human race to a truly unimaginable extent?” Looking at the paintings of Walton Ford in a book, you might mistake them for the watercolors of a nineteenth-century naturalist: they are annotated in longhand script, and yellowed at the edges as if stained by time and voyage. Something’s always outrageously off, though: the gorilla is holding a human skull; a couple of parrots are mating on the shaft of an elephant’s penis. In his early riffs on Audubon prints, Ford painted birds mid-slaughter: his American Flamingo (1992) flails head over heels after being shot with a rifle, and an eagle with its foot in a trap billows smoke from its beak (Audubon, in search of a painless method of execution, tried unsuccessfully to asphyxiate an eagle with sulfurous gas).

Looking at the paintings of Walton Ford in a book, you might mistake them for the watercolors of a nineteenth-century naturalist: they are annotated in longhand script, and yellowed at the edges as if stained by time and voyage. Something’s always outrageously off, though: the gorilla is holding a human skull; a couple of parrots are mating on the shaft of an elephant’s penis. In his early riffs on Audubon prints, Ford painted birds mid-slaughter: his American Flamingo (1992) flails head over heels after being shot with a rifle, and an eagle with its foot in a trap billows smoke from its beak (Audubon, in search of a painless method of execution, tried unsuccessfully to asphyxiate an eagle with sulfurous gas). By day, some of the most dangerous animals in the world lurk deep inside this cave. Come night, the tiny fruit bats whoosh out, tens of thousands of them at a time, filling the air with their high-pitched chirping before disappearing into the black sky. The bats carry the deadly Marburg virus, as fearsome and mysterious as its cousin Ebola. Scientists know that the virus starts in these animals, and they know that when it spreads to humans it is lethal — Marburg kills up to 9 in 10 of its victims, sometimes within a week. But they don’t know much about what happens in between. That’s where the bats come Prevention traveled here to track their movements in the hopes that spying on their nightly escapades could help prevent the spread of one of the world’s most dreaded diseases. Because there is a close relationship between Marburg and Ebola, the scientists are also hopeful that progress on one virus could help solve the puzzle of the other.

By day, some of the most dangerous animals in the world lurk deep inside this cave. Come night, the tiny fruit bats whoosh out, tens of thousands of them at a time, filling the air with their high-pitched chirping before disappearing into the black sky. The bats carry the deadly Marburg virus, as fearsome and mysterious as its cousin Ebola. Scientists know that the virus starts in these animals, and they know that when it spreads to humans it is lethal — Marburg kills up to 9 in 10 of its victims, sometimes within a week. But they don’t know much about what happens in between. That’s where the bats come Prevention traveled here to track their movements in the hopes that spying on their nightly escapades could help prevent the spread of one of the world’s most dreaded diseases. Because there is a close relationship between Marburg and Ebola, the scientists are also hopeful that progress on one virus could help solve the puzzle of the other. Since I first read Plato’s Symposium, I have been fond of Aristophanes’ account of the origin of love. The tale goes something like this. Human beings used to be spherical creatures with four legs, four arms, and two faces divided evenly between each side. We also used to come in three distinct varieties. Men were those composed of two male halves, women were those composed of two female halves, and the androgynous were those composed of both a male and a female half.

Since I first read Plato’s Symposium, I have been fond of Aristophanes’ account of the origin of love. The tale goes something like this. Human beings used to be spherical creatures with four legs, four arms, and two faces divided evenly between each side. We also used to come in three distinct varieties. Men were those composed of two male halves, women were those composed of two female halves, and the androgynous were those composed of both a male and a female half. The relationship between the humanities and the sciences, including some quarters of the social sciences, has become strained, to put it mildly. Developments in cognitive neuroscience and other fields — from sophisticated brain-imaging techniques to increasingly detailed knowledge of human genetics — promise to revolutionize our knowledge of human behavior. And these changes have propelled a new, more hard-edged round in the science wars. In 2002, Steven Pinker, in his best-selling The Blank Slate, chastised the humanities for presenting culture as a malleable product of human will. While the first science wars, fought in the 1990s, focused on broad questions regarding the basis of scientific knowledge, today science warriors accuse the humanities of ignoring human nature, and especially natural human differences.

The relationship between the humanities and the sciences, including some quarters of the social sciences, has become strained, to put it mildly. Developments in cognitive neuroscience and other fields — from sophisticated brain-imaging techniques to increasingly detailed knowledge of human genetics — promise to revolutionize our knowledge of human behavior. And these changes have propelled a new, more hard-edged round in the science wars. In 2002, Steven Pinker, in his best-selling The Blank Slate, chastised the humanities for presenting culture as a malleable product of human will. While the first science wars, fought in the 1990s, focused on broad questions regarding the basis of scientific knowledge, today science warriors accuse the humanities of ignoring human nature, and especially natural human differences. I regret never really getting to know my dad

I regret never really getting to know my dad Plath grows up in Cold War America, deceived by a God who let her father die, wanting more than anything to be a writer and to marry a man who would make her feel like she had a vodka sword in her stomach, always. And she gets it when she arrives in Cambridge in 1956, meets her black marauder and marries him ‘in mother’s gift of a pink knit dress’ three and a half months later. (When I got married at 28 to the man I met at Oxford at 19, I married in pink partly under the influence of Ted and Sylvia, partly because my mother had also married, though not knowing or caring about Plath, in a pink knitted dress in 1977. I liked the resonances, then.) But the world, even when it gives her what she wants, also doesn’t. Literary success is baseless, fleeting; the marriage dissolves in betrayal, arguments, abandonment. The hard work has come to ash. Awake at 4 a.m. when the sleeping pills wear off, she finds a voice and writes the poems of her life, ones that will make her a myth like Lazarus, like Lorelei. But now she knows that her conception of her life, psychological and otherwise, is no longer tenable, and never was. Now what? ‘I love you for listening,’ Plath, abandoned and alone, tells her analyst Ruth Beuscher in a letter late in 1962. The rest of us are listening at last.

Plath grows up in Cold War America, deceived by a God who let her father die, wanting more than anything to be a writer and to marry a man who would make her feel like she had a vodka sword in her stomach, always. And she gets it when she arrives in Cambridge in 1956, meets her black marauder and marries him ‘in mother’s gift of a pink knit dress’ three and a half months later. (When I got married at 28 to the man I met at Oxford at 19, I married in pink partly under the influence of Ted and Sylvia, partly because my mother had also married, though not knowing or caring about Plath, in a pink knitted dress in 1977. I liked the resonances, then.) But the world, even when it gives her what she wants, also doesn’t. Literary success is baseless, fleeting; the marriage dissolves in betrayal, arguments, abandonment. The hard work has come to ash. Awake at 4 a.m. when the sleeping pills wear off, she finds a voice and writes the poems of her life, ones that will make her a myth like Lazarus, like Lorelei. But now she knows that her conception of her life, psychological and otherwise, is no longer tenable, and never was. Now what? ‘I love you for listening,’ Plath, abandoned and alone, tells her analyst Ruth Beuscher in a letter late in 1962. The rest of us are listening at last.