Month: December 2018

Cyril Pahinui (1950 – 2018)

Pete Shelley (1955 – 2018)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=terg_LPT3X0

Tears on the Bench

Bethany Schneider in Avidly:

Here’s a little lesson about crying – historical crying – from another class I teach, “Literatures of American Indian Removal.” Once upon a time, the State of New Hampshire tried to claim Dartmouth College as its state university. In 1818, the case went to the Supreme Court, where John Marshall, as chief justice, presided. Dartmouth was represented by Daniel Webster. . . . It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet, there are those who love it . . . In an impassioned speech, Webster cited love as the private passion that draws a fairy circle of protection around the small college, keeping away publics that cannot possibly feel correctly. Webster’s oratory was so moving that the great judge wept openly on the bench. John Marshall, who shaped the Supreme Court into the powerful third arm of government that we now rely on it to be, was moved to tears. Dartmouth was founded to educate Native men, but immediately abandoned that project. That abandonment was partly why New Hampshire felt it could be claimed as public. But Marshall’s court decided it would remain private. The decision is a cornerstone of the American corporation. The corporation, he wrote, “is chiefly for the purpose of clothing bodies of men, in succession, with these qualities and capacities that corporations were invented, and are in use. By these means, a perpetual succession of individuals are capable of acting for the promotion of the particular object like one immortal being.” Corporations are immortal bodies, made up of successive generations of white men clothed in the invisibility cloak of power.

Here’s a little lesson about crying – historical crying – from another class I teach, “Literatures of American Indian Removal.” Once upon a time, the State of New Hampshire tried to claim Dartmouth College as its state university. In 1818, the case went to the Supreme Court, where John Marshall, as chief justice, presided. Dartmouth was represented by Daniel Webster. . . . It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet, there are those who love it . . . In an impassioned speech, Webster cited love as the private passion that draws a fairy circle of protection around the small college, keeping away publics that cannot possibly feel correctly. Webster’s oratory was so moving that the great judge wept openly on the bench. John Marshall, who shaped the Supreme Court into the powerful third arm of government that we now rely on it to be, was moved to tears. Dartmouth was founded to educate Native men, but immediately abandoned that project. That abandonment was partly why New Hampshire felt it could be claimed as public. But Marshall’s court decided it would remain private. The decision is a cornerstone of the American corporation. The corporation, he wrote, “is chiefly for the purpose of clothing bodies of men, in succession, with these qualities and capacities that corporations were invented, and are in use. By these means, a perpetual succession of individuals are capable of acting for the promotion of the particular object like one immortal being.” Corporations are immortal bodies, made up of successive generations of white men clothed in the invisibility cloak of power.

I teach this decision alongside Marshall’s Cherokee cases, partly because “Dartmouth v. Woodward” is about Native Americans, and partly to enable a discussion about the emotions of immortal “fathers,” and the ways that the “body corporate,” as Marshall described it, disciplines and disperses the bodies, and the emotions, of those who do not fit. In 1831, Marshall rejected the Cherokee Nation’s case against the State of Georgia, which wanted to force them to remove. Marshall’s decision ends with these words; “If it be true that wrongs have been inflicted and that still greater are to be apprehended, this is not the tribunal which can redress the past or prevent the future.”

More here.

Sunday Poem

It Happens Like This

I was outside St. Cecelia’s Rectory

smoking a cigarette when a goat appeared beside me.

It was mostly black and white, with a little reddish

brown here and there. When I started to walk away,

it followed. I was amused and delighted, but wondered

what the laws were on this kind of thing. There’s

a leash law for dogs, but what about goats? People

smiled at me and admired the goat. “It’s not my goat,”

I explained. “It’s the town’s goat. I’m just taking

my turn caring for it.” “I didn’t know we had a goat,”

one of them said. “I wonder when my turn is.” “Soon,”

I said. “Be patient. Your time is coming.” The goat

stayed by my side. It stopped when I stopped. It looked

up at me and I stared into its eyes. I felt he knew

everything essential about me. We walked on. A police-

man on his beat looked us over. “That’s a mighty

fine goat you got there,” he said, stopping to admire.

“It’s the town’s goat,” I said. “His family goes back

three-hundred years with us,” I said, “from the beginning.”

The officer leaned forward to touch him, then stopped

and looked up at me. “Mind if I pat him?” he asked.

“Touching this goat will change your life,” I said.

“It’s your decision.” He thought real hard for a minute,

and then stood up and said, “What’s his name?” “He’s

called the Prince of Peace,” I said. “God! This town

is like a fairy tale. Everywhere you turn there’s mystery

and wonder. And I’m just a child playing cops and robbers

forever. Please forgive me if I cry.” “We forgive you,

Officer,” I said. “And we understand why you, more than

anybody, should never touch the Prince.” The goat and

I walked on. It was getting dark and we were beginning

to wonder where we would spend the night.

by James Tate

from Lost River

Sarabande Books, Inc. 2003

Saturday Poem

Key

I straighten out my mother

attach her to the backrest

fold her hands

place them on the table.

Lift her head

turn it to me

tie the bib.

The spoon knocks on her teeth

like a key

I once turned inside a toy

and didn’t understand

how it suddenly moved

why it suddenly stopped.

.

translation: 2018, Linda Zisquit

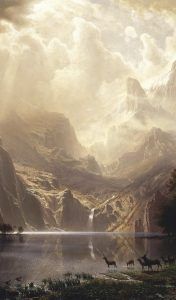

At once tiny and huge: what is this feeling we call ‘sublime’?

Sandy Shapshay in Aeon:

Have you ever felt awe and exhilaration while contemplating a vista of jagged, snow-capped mountains? Or been fascinated but also a bit unsettled while beholding a thunderous waterfall such as Niagara? Or felt existentially insignificant but strangely exalted while gazing up at the clear, starry night sky? If so, then you’ve had an experience of what philosophers from the mid-18th century to the present call the sublime. It is an aesthetic experience that modern, Western philosophers often theorise about, as well as, more recently, experimental psychologists and neuroscientists in the field of neuroaesthetics.

Have you ever felt awe and exhilaration while contemplating a vista of jagged, snow-capped mountains? Or been fascinated but also a bit unsettled while beholding a thunderous waterfall such as Niagara? Or felt existentially insignificant but strangely exalted while gazing up at the clear, starry night sky? If so, then you’ve had an experience of what philosophers from the mid-18th century to the present call the sublime. It is an aesthetic experience that modern, Western philosophers often theorise about, as well as, more recently, experimental psychologists and neuroscientists in the field of neuroaesthetics.

Responses to the sublime are puzzling. While the 18th century saw ‘the beautiful’ as a wholly pleasurable experience of typically delicate, harmonious, balanced, smooth and polished objects, the sublime was understood largely as its opposite: a mix of pain and pleasure, experienced in the presence of typically vast, formless, threatening, overwhelming natural environments or phenomena. Thus the philosopher Edmund Burke in 1756 describes sublime pleasure in oxymoronic terms as a ‘delightful horror’ and a ‘sort of tranquility tinged with terror’. Immanuel Kant in 1790 describes it as a ‘negative’ rather than a ‘positive pleasure’, in which ‘the mind is not merely attracted by the object, but is also always reciprocally repelled by it’. It became a problem to explain why the sublime should be experienced overall with positive affect and valued so highly, given that it was seen to also involve an element of pain.

More here.

Is Green Growth Possible? A Debate

From the Institute for New Economic Thinking:

In this series, economists debate whether catastrophic global warming can be stopped while maintaining current levels of economic growth. Enno Schröder, Servaas Storm, Gregor Semieniuk, Lance Taylor, and Armon Rezai find there is a tradeoff between growth and decarbonization, while Michael Grubb responds with more optimism.

In this series, economists debate whether catastrophic global warming can be stopped while maintaining current levels of economic growth. Enno Schröder, Servaas Storm, Gregor Semieniuk, Lance Taylor, and Armon Rezai find there is a tradeoff between growth and decarbonization, while Michael Grubb responds with more optimism.

More here.

Europe’s Political Economy: The Italy Debate

Adam Tooze at his own website:

Right now the greatest threat to the eurozone and one of the most significant tail risks for the world economy is the unresolved standoff over the Italian budget and its public debt running to 133% of GDP. If Italy were not a member of the eurozone, if it had its own central bank debt at this level would be a matter of concern rather than alarm. But Italy is tied to the euro, the response of the ECB in a crisis is unpredictable and speculation about Italy leaving the euro is idle. Both the political and economics costs are too vast to contemplate seriously.

Right now the greatest threat to the eurozone and one of the most significant tail risks for the world economy is the unresolved standoff over the Italian budget and its public debt running to 133% of GDP. If Italy were not a member of the eurozone, if it had its own central bank debt at this level would be a matter of concern rather than alarm. But Italy is tied to the euro, the response of the ECB in a crisis is unpredictable and speculation about Italy leaving the euro is idle. Both the political and economics costs are too vast to contemplate seriously.

Last week I contributed a New York Times op-ed about the stand off and its risks: How does the EU think this is going to end?

My main theme was that the Rome government, however unpalatable its politics, has to be taken seriously as an expression of the crisis of Italy’s political economy. There are even worse political constellations, some of which might offer a fiscal deal more amenable to the Commission, but would be disastrous for Europe in political terms. For the EU to offer only discipline risks a further turn for the worse.

More here.

Language and Progress: A Conversation with Steven Pinker and John McWhorter

It’s Time to Study Whether Eating Particular Diets Can Help Heal Us

Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New York Times:

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg, a German physiologist, demonstrated that tumor cells, unlike most normal cells, metabolize glucose using alternative pathways to sustain their rapid growth, provoking the idea that sugar might promote tumor growth. You might therefore expect the medical literature on “sugar feeding cancer” to be rich with deep randomized or prospective studies. Instead, when I searched, I could find only a handful of such trials. In 2012, a team at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston divided patients with Stage 3 colon cancer into different groups based on their dietary consumption, and determined their survival and rate of relapse. The study generated provocative data — but far from an open-and-shut case. Patients whose diets consisted of foods with a high glycemic load (a measure of how much blood glucose rises after eating a typical portion of a food) generally had shorter survival than patients with lower glycemic load. But a higher glycemic index (a measure of how much 50 grams of carbohydrate from a food, which may require eating a huge portion, raises blood glucose) or total fructose intake had no significant association with overall survival or relapse.

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg, a German physiologist, demonstrated that tumor cells, unlike most normal cells, metabolize glucose using alternative pathways to sustain their rapid growth, provoking the idea that sugar might promote tumor growth. You might therefore expect the medical literature on “sugar feeding cancer” to be rich with deep randomized or prospective studies. Instead, when I searched, I could find only a handful of such trials. In 2012, a team at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston divided patients with Stage 3 colon cancer into different groups based on their dietary consumption, and determined their survival and rate of relapse. The study generated provocative data — but far from an open-and-shut case. Patients whose diets consisted of foods with a high glycemic load (a measure of how much blood glucose rises after eating a typical portion of a food) generally had shorter survival than patients with lower glycemic load. But a higher glycemic index (a measure of how much 50 grams of carbohydrate from a food, which may require eating a huge portion, raises blood glucose) or total fructose intake had no significant association with overall survival or relapse.

While the effect of sugar on cancer was being explored in scattered studies, the so-called ketogenic diet, which consists of high fat, moderate protein and low carbohydrate, was also being promoted. It isn’t sugars that are feeding the tumor, the logic runs. It’s insulin — the hormone that is released when glucose enters the blood. By reducing carbohydrates and thus keeping a strong curb on insulin, the keto diet would decrease the insulin exposure of tumor cells, and so restrict tumor growth. Yet the search for “ketogenic diet, randomized study and cancer” in the National Library of Medicine database returned a mere 11 articles. Not one of them reported an effect on a patient’s survival, or relapse.

More here.

Kate Bush and Me

David Mitchell at The Guardian:

Aerial is Kate’s third masterpiece, along with The Dreaming and Hounds of Love. What constitutes a “masterpiece” is only established by the ultimate critic, time; but even producing three contenders for the title in a single career puts a songwriter in the most exclusive company. “Bertie” is a madrigal about her young son, whose birth and upbringing accounted in no small part for the 12-year hiatus. By now my wife and I had a small child of our own whose toothy grin was for us, too, “The most truly fantastic smile / I’ve ever seen”. “Mrs Bartolozzi”, surely the only song by a major artist whose lyrics include washing machine onomatopoeia, portrays a housekeeper of a certain age. The drudgery of her life smothers her own memories and desires, and puts me in mind of a 21st-century Miss Kenton from Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. The song “How to Be Invisible” contains a Macbeth-esque recipe for invisibility that is, Kate-ishly, both quotidian and magical: “Eye of Braille / Hem of Anorak / Stem of Wallflower / Hair of Doormat.” Disc one’s last song is my desert island Kate song: “A Coral Room”. Musically, this ballad for piano and vocal is one of her sparsest. Lyrically, it’s one of her richest, describing an underwater city, dreamy and abandoned and swaying and recalling Debussy’s prelude La Cathédrale Engloutie. The city is deep memory, crawled over by the spider of time, perhaps from the hills of time in “Moments of Pleasure”. Speedboats fly above and planes – perhaps a black Spitfire or two – come crashing down.

Aerial is Kate’s third masterpiece, along with The Dreaming and Hounds of Love. What constitutes a “masterpiece” is only established by the ultimate critic, time; but even producing three contenders for the title in a single career puts a songwriter in the most exclusive company. “Bertie” is a madrigal about her young son, whose birth and upbringing accounted in no small part for the 12-year hiatus. By now my wife and I had a small child of our own whose toothy grin was for us, too, “The most truly fantastic smile / I’ve ever seen”. “Mrs Bartolozzi”, surely the only song by a major artist whose lyrics include washing machine onomatopoeia, portrays a housekeeper of a certain age. The drudgery of her life smothers her own memories and desires, and puts me in mind of a 21st-century Miss Kenton from Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. The song “How to Be Invisible” contains a Macbeth-esque recipe for invisibility that is, Kate-ishly, both quotidian and magical: “Eye of Braille / Hem of Anorak / Stem of Wallflower / Hair of Doormat.” Disc one’s last song is my desert island Kate song: “A Coral Room”. Musically, this ballad for piano and vocal is one of her sparsest. Lyrically, it’s one of her richest, describing an underwater city, dreamy and abandoned and swaying and recalling Debussy’s prelude La Cathédrale Engloutie. The city is deep memory, crawled over by the spider of time, perhaps from the hills of time in “Moments of Pleasure”. Speedboats fly above and planes – perhaps a black Spitfire or two – come crashing down.

more here.

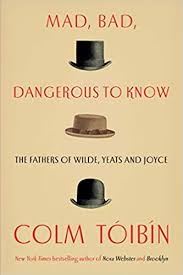

The Fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce

John Banville at Literary Review:

This book is, in its sly way, far more substantial than it might at first seem – more, indeed, than it presents itself as being. Colm Tóibín’s subject is the influence of their fathers on the artistic thought, attitude and writings of three great Irish literary artists: Oscar Wilde, W B Yeats and James Joyce. What Tóibín has produced is not only a group portrait of three men who in their way were almost as brilliant as their sons, but also an illuminating meditation on the familial sources of artistic inspiration.

This book is, in its sly way, far more substantial than it might at first seem – more, indeed, than it presents itself as being. Colm Tóibín’s subject is the influence of their fathers on the artistic thought, attitude and writings of three great Irish literary artists: Oscar Wilde, W B Yeats and James Joyce. What Tóibín has produced is not only a group portrait of three men who in their way were almost as brilliant as their sons, but also an illuminating meditation on the familial sources of artistic inspiration.

Happily, Tóibín is no Freudian and avoids obfuscating speculations on, for instance, the Oedipus complex, although he does cheerfully acknowledge that the three sons often chafed under the burdens placed on them by their variously annoying, interfering, disreputable and importunate paters. If it is not easy being a father, it is sometimes nigh impossible to be the father’s offspring. As Kingsley Amis pointed out, the greatest gift a father can bestow on his son is to die early.

more here.

Sing, Goddess

Patricia Storace at the NYRB:

The Silence of the Girls, Pat Barker’s unsentimental and beautiful new novel, tells the story of the Iliad as experienced by women captives, from inside the Greek camp overlooking the walls of the besieged city of Troy. They are the Greek heroes’ prizes, taken from conquered outlying towns and villages to be prostitutes, domestic workers, and, on occasion, wives. Herodotus, in his Histories, tells of the Ionian Greek customs with regard to their captured women: they

married Carian girls, whose parents they had killed. The fact that these women were forced into marriage after the murder of their fathers, husbands, and sons was the origin of the law, established by oath and passed down to their female descendants, forbidding them to sit at table with their husbands or to address them by name.

The novel is told, mostly in the first person, by Briseis, the captive queen awarded to Achilles, the Greeks’ greatest warrior. She becomes the motive for the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek troops, and the resulting destruction their troops suffer, caused by the two men’s personal feud.

more here.

Now you sea me: meet the ocean’s endangered animals

Samantha Weinberg in More Intelligent Life:

Philip Hamilton, a seasoned underwater photographer, has spent the past five years seeking out the stars of the seas, but also the smaller, lesser-known creatures. In his book, “Call of the Blue”, there are pin-sharp close-ups of a hawksbill turtle and a great white shark – and of a tiny xeno crab and a strange group of Lambert’s worm sea cucumbers. There are also great splashes of colourful reefs and gaudy anemones, and a silvery view into the mouth of a whale shark, the largest fish in the world. Coursing through this visual warmth is an icy current: essays and interviews with scientists, photographers and “ocean guardians” – people who are devoted to protecting the oceans. Though they are clearly fascinated by all things oceanic, the stories they tell are more terrifying than any tiger shark. The waters are warming; as a result, corals are bleaching and dying, leaving creatures of all types homeless and vulnerable. We are catching too many fish and filling the oceans with plastic. “Large marine animals have survived five mass extinctions millions of years ago,” Hamilton writes. “However, many of them are now at the brink of disappearing for good.”

Philip Hamilton, a seasoned underwater photographer, has spent the past five years seeking out the stars of the seas, but also the smaller, lesser-known creatures. In his book, “Call of the Blue”, there are pin-sharp close-ups of a hawksbill turtle and a great white shark – and of a tiny xeno crab and a strange group of Lambert’s worm sea cucumbers. There are also great splashes of colourful reefs and gaudy anemones, and a silvery view into the mouth of a whale shark, the largest fish in the world. Coursing through this visual warmth is an icy current: essays and interviews with scientists, photographers and “ocean guardians” – people who are devoted to protecting the oceans. Though they are clearly fascinated by all things oceanic, the stories they tell are more terrifying than any tiger shark. The waters are warming; as a result, corals are bleaching and dying, leaving creatures of all types homeless and vulnerable. We are catching too many fish and filling the oceans with plastic. “Large marine animals have survived five mass extinctions millions of years ago,” Hamilton writes. “However, many of them are now at the brink of disappearing for good.”

It was, he admits, a calculated decision to mix beautiful pictures with harsh words: “I’m not trying to deceive myself [by] hiding the problems and pretending that everything is perfect out there.” Yet he realised that the book would go unnoticed without beautiful photographs. “A single photo can be the most powerful conservation tool,” he says. This magnificent book is his call to arms. Let’s hope it works.

More here.

Hannah Arendt On Why It’s Urgent To Break Your Bubble

Siobhan Kattago at the Institute of Art and Ideas:

In the current political climate of populism and xenophobia, it is tempting to simply close the door and withdraw from public affairs. Indeed, there is a pervading sense that there is no alternative to our polarised politics, neoliberal capitalism and corruption. Pleas for solidarity among nation-states seem to be easily overshadowed by resentment towards foreigners and nostalgia for lost national glory. And yet, it is precisely such retreat into the private realm that Hannah Arendt warned against during the 20th century. It is during moments of political crisis that individual potential for new beginnings matters most; it is in times of political division that we are faced with the task of cooperating and finding a way to share our fragile world.

In the current political climate of populism and xenophobia, it is tempting to simply close the door and withdraw from public affairs. Indeed, there is a pervading sense that there is no alternative to our polarised politics, neoliberal capitalism and corruption. Pleas for solidarity among nation-states seem to be easily overshadowed by resentment towards foreigners and nostalgia for lost national glory. And yet, it is precisely such retreat into the private realm that Hannah Arendt warned against during the 20th century. It is during moments of political crisis that individual potential for new beginnings matters most; it is in times of political division that we are faced with the task of cooperating and finding a way to share our fragile world.

Withdrawal from public affairs is more than a sign of cynical escapism and alienation; for Arendt, it denotes the situation of ‘worldlessness,’ whereby the sense of shared reality begins to disintegrate. Worldlessness is like a desert that dries up the space between people. By resigning ourselves to the belief that political engagement is futile, we remove ourselves from the world and from one another. As Arendt argues in Crises in the Republic (1972) and her posthumously published The Promise of Politics (1993), when we lose touch with the world, we experience a dangerous ‘remoteness from reality.’

More here.

Imagining What Happens When the Robots Take the Wheel

Matthew DeBord in the New York Times:

An appalling statistic appears toward the end of “No One at the Wheel,” Samuel Schwartz’s valuable primer on self-driving cars: In the century since the automobile arrived on the scene, 70 million people have been killed by it, and four billion injured.

An appalling statistic appears toward the end of “No One at the Wheel,” Samuel Schwartz’s valuable primer on self-driving cars: In the century since the automobile arrived on the scene, 70 million people have been killed by it, and four billion injured.

Schwartz, who served as New York City’s traffic commissioner in the 1980s, was nicknamed “Gridlock Sam” for his devotion to the conundrum of traffic (and for coining the loathsome term). He knows everything about how cars and people don’t get along, having been on the front lines. This book — written in an earnest, conversational style — is his attempt to grapple with a fresh threat that’s appeared after decades of progress.

Futurists may have promised us flying cars, but what we’re going to get instead are driverless ones, and Schwartz’s is the first comprehensive analysis of what that will mean on the ground. Most likely, there will be far fewer fatalities. With nearly 40,000 people killed in 2017 in the United States alone, that’s a huge benefit. But cars that can drive themselves will bring with them other knotty societal problems.

More here.

Noam Chomsky and the Question of Individual Choice in a Vastly Unequal World

Anjan Basu in The Wire:

As a scientist, Chomsky always locates the question of rational choice at the centre of any debate about issues of real public interest. That is not to say, though, that he is concerned with rationality alone. Far from it, in fact. Chomsky has written extensively about how a ‘rational’ debate can be so constructed as to completely undermine – indeed, subvert – the irreducible moral values implicit in a choice.

As a scientist, Chomsky always locates the question of rational choice at the centre of any debate about issues of real public interest. That is not to say, though, that he is concerned with rationality alone. Far from it, in fact. Chomsky has written extensively about how a ‘rational’ debate can be so constructed as to completely undermine – indeed, subvert – the irreducible moral values implicit in a choice.

With withering scorn, he wrote in his 1969 classic, American Power and the New Mandarins, about well-known American liberals who managed to successfully mask the immorality of the war on Vietnam, projecting the debate around the war as primarily one about the proportionality of its costs to its likely outcome. In a talk given at Harvard in June, 1966 in the course of the anti-war protests– later published as the celebrated essay The Responsibility of Intellectuals – Chomsky argues that Americans “can hardly avoid asking (themselves) to what extent the American people bear responsibility for the savage American assault on a largely helpless rural population in Vietnam”.

More here.

Yuval Noah Harari’s talk at Google

Reflections on the Mail Coach (1849)

Thomas de Quincey at berfrois:

No dignity is perfect which does not at some point ally itself with the mysterious. The connexion of the mail with the state and the executive government—a connexion obvious, but yet not strictly defined—gave to the whole mail establishment an official grandeur which did us service on the roads, and invested us with seasonable terrors. Not the less impressive were those terrors because their legal limits were imperfectly ascertained. Look at those turnpike gates: with what deferential hurry, with what an obedient start, they fly open at our approach! Look at that long line of carts and carters ahead, audaciously usurping the very crest of the road. Ah! traitors, they do not hear us as yet; but, as soon as the dreadful blast of our horn reaches them with proclamation of our approach, see with what frenzy of trepidation they fly to their horses’ heads, and deprecate our wrath by the precipitation of their crane-neck quarterings. Treason they feel to be their crime; each individual carter feels himself under the ban of confiscation and attainder; his blood is attainted through six generations; and nothing is wanting but the headsman and his axe, the block and the sawdust, to close up the vista of his horrors. What! shall it be within benefit of clergy to delay the king’s message on the high road?—to interrupt the great respirations, ebb and flood, systole and diastole, of the national intercourse?—to endanger the safety of tidings running day and night between all nations and languages?

No dignity is perfect which does not at some point ally itself with the mysterious. The connexion of the mail with the state and the executive government—a connexion obvious, but yet not strictly defined—gave to the whole mail establishment an official grandeur which did us service on the roads, and invested us with seasonable terrors. Not the less impressive were those terrors because their legal limits were imperfectly ascertained. Look at those turnpike gates: with what deferential hurry, with what an obedient start, they fly open at our approach! Look at that long line of carts and carters ahead, audaciously usurping the very crest of the road. Ah! traitors, they do not hear us as yet; but, as soon as the dreadful blast of our horn reaches them with proclamation of our approach, see with what frenzy of trepidation they fly to their horses’ heads, and deprecate our wrath by the precipitation of their crane-neck quarterings. Treason they feel to be their crime; each individual carter feels himself under the ban of confiscation and attainder; his blood is attainted through six generations; and nothing is wanting but the headsman and his axe, the block and the sawdust, to close up the vista of his horrors. What! shall it be within benefit of clergy to delay the king’s message on the high road?—to interrupt the great respirations, ebb and flood, systole and diastole, of the national intercourse?—to endanger the safety of tidings running day and night between all nations and languages?

more here.