by Nickolas Calabrese

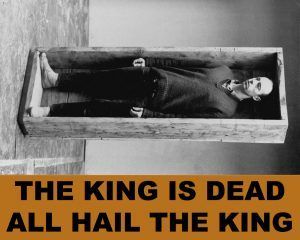

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

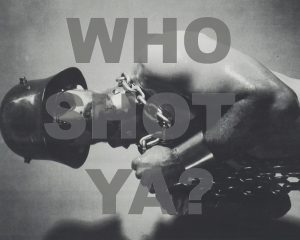

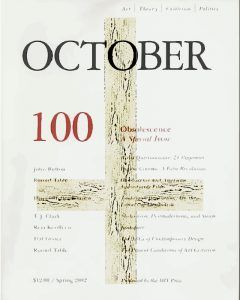

And that is actually what this obituary is about: death, as the ultimate gesture, is the last revision to the works of artists. Death is as real as it gets. And the lives of artists are, for better or for worse, tethered to their works. Sometimes people argue for the opposite, that an artist’s works should be evaluated independently of the maker. But that’s just willful ignorance and doesn’t help anybody understand anything. A well-informed audience takes the artist into account – and how dramatic is it for someone to die!? It is equally true that anybody’s life is altered once they die. I remember having a lot of emotional animus towards a family member while they were alive, considering them manipulative and far too malevolent for their lot; after they died, however, I reevaluated all of those feelings and appreciated (correctly or not) that their agenda was not malicious, but intended rather to shape the moral parameters of those around them. But the artist is a more persuasive case to study because of their public contribution. Using a very clear example, consider The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Who Shot Ya?”. This song, in B.I.G.’s lifetime, was an instance of theatrical machismo, quite a real threat, but also playing the hyperbolic part that many rappers do. After his murder though, it becomes an oracular exercise in grief and loss. It was exciting when it came out, but I find it hard to listen to now without wincing at how stupid his death was, and how irresponsibly the lead up to the East Coast/West Coast beef played out. Or someone like photographer Francesca Woodman, whose experimental nudes, while not reviewed during her short lifespan with any seriousness, were doubtless mysterious, erotic, focused on youth and vitality, and formal kin to early nude Greek and Roman sculpture. While all of this remains true after her suicide, the photos also take on melancholy notes related to her severe depression, showing completely exposed images of a woman in the throes of mental illness. Of course the two examples stated are extreme: murder and suicide respectively. Morris was old and accomplished when the octogenarian perished of pneumonia last month. Morris was a remarkable artist, engaged in the kind of aesthetic research usually reserved for academics. But I have real concerns about what happens to his aesthetic legacy now that he’s dead. What matters when we think of him? Will the butchers of art history at October Journal, playing the part of psychopomps, escort Morris to an afterlife they believe suited for his legacy? I worry the answer to this is the stereotypical “reinterpretation”, or “redescription” as his one-time collaborator Donald Davidson might put it, but I’ll there in a minute. The issue with an artist’s death is that it has real consequences for how their work is viewed, as indicated above. This is especially true when art historians enter into the mix, because their brand of interpretation can be nearly unrecognizable to what the term normally means. A large part of the game in art history is to stake an ownership on a deceased artist’s legacy. That is how books are sold and how tenure-track positions are cemented.

And that is actually what this obituary is about: death, as the ultimate gesture, is the last revision to the works of artists. Death is as real as it gets. And the lives of artists are, for better or for worse, tethered to their works. Sometimes people argue for the opposite, that an artist’s works should be evaluated independently of the maker. But that’s just willful ignorance and doesn’t help anybody understand anything. A well-informed audience takes the artist into account – and how dramatic is it for someone to die!? It is equally true that anybody’s life is altered once they die. I remember having a lot of emotional animus towards a family member while they were alive, considering them manipulative and far too malevolent for their lot; after they died, however, I reevaluated all of those feelings and appreciated (correctly or not) that their agenda was not malicious, but intended rather to shape the moral parameters of those around them. But the artist is a more persuasive case to study because of their public contribution. Using a very clear example, consider The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Who Shot Ya?”. This song, in B.I.G.’s lifetime, was an instance of theatrical machismo, quite a real threat, but also playing the hyperbolic part that many rappers do. After his murder though, it becomes an oracular exercise in grief and loss. It was exciting when it came out, but I find it hard to listen to now without wincing at how stupid his death was, and how irresponsibly the lead up to the East Coast/West Coast beef played out. Or someone like photographer Francesca Woodman, whose experimental nudes, while not reviewed during her short lifespan with any seriousness, were doubtless mysterious, erotic, focused on youth and vitality, and formal kin to early nude Greek and Roman sculpture. While all of this remains true after her suicide, the photos also take on melancholy notes related to her severe depression, showing completely exposed images of a woman in the throes of mental illness. Of course the two examples stated are extreme: murder and suicide respectively. Morris was old and accomplished when the octogenarian perished of pneumonia last month. Morris was a remarkable artist, engaged in the kind of aesthetic research usually reserved for academics. But I have real concerns about what happens to his aesthetic legacy now that he’s dead. What matters when we think of him? Will the butchers of art history at October Journal, playing the part of psychopomps, escort Morris to an afterlife they believe suited for his legacy? I worry the answer to this is the stereotypical “reinterpretation”, or “redescription” as his one-time collaborator Donald Davidson might put it, but I’ll there in a minute. The issue with an artist’s death is that it has real consequences for how their work is viewed, as indicated above. This is especially true when art historians enter into the mix, because their brand of interpretation can be nearly unrecognizable to what the term normally means. A large part of the game in art history is to stake an ownership on a deceased artist’s legacy. That is how books are sold and how tenure-track positions are cemented.

“What am I doing here?” This is how eminent American philosopher Donald Davidson begins an essay titled “The Third Man” in Critical Inquiry contending with the fact that he has no idea why Robert Morris has used his writings in his series of drawings Blind Time IV: Drawing with Davidson, so-called because he made them blindfolded according to a series of self-imposed rules. Morris used Davidson’s writings on epistemology and action to prove some point in the production of the Blind drawings. Davidson eventually played along, writing his text in concert with a text produced by Morris in the same journal. That the artist would make interpretive use of another’s work is especially telling in the present context. It sounds an awful lot like the entire project of the domain called Art History. That is, what art historians do is take an artist, often dead, and interpret their work according to the historian’s personal project. Where the artist leaves off, the art historian picks up. The death then, is the final legitimate act by an artist, leaving the rest to interpretation. But this gives the art historian enough agency to make of the legacy what they will. Of course, as Epicurus noted, death is not an act. It is annihilation of the mind. He even states that “the dead” do not exist. Death is not an action with a result, it is simply a cessation. If we are to take massive liberties and juxtapose this with Davidson’s ideas about actions, we get a fuller picture of both Morris’ insight into his own work, and how he history may treat him in turn. In one of the Blind drawings Morris quotes Davidson:

“His behaviour seems strange, alien, outré, pointless, out of character, disconnected; or perhaps we cannot even recognize an action in it. When we learn his reason, we have an interpretation, a new description of what he did which fits into a familiar picture…Here it is tempting to draw two conclusions that do not follow. First, we can’t infer, from the fact that giving reasons merely redescribes the action and that causes are separate from effects, that therefore reasons are not causes, reasons, being beliefs and attitudes, are certainly not identical with actions; but, more important, events are often redescribed in terms of their causes. Second, it is an error to think that, because placing the action in a larger pattern explains it, therefore we now understand the sort of explanation involved.”

Davidson is saying a lot, and I won’t pretend to understand everything he writes as it can be excruciatingly dense at times, but here he is saying that it would be an error to use a person’s reasons or their actions to determine what their intentions are, that is, what was the actual cause for whatever it is that they did. In other words, actions cannot be reduced to intentions. The process of redescription does not offer a causal relationship with regards to what a person intended and what they did. Dealing with death means dealing with redescription of some sort. Morris’ work and life are bound to be resdescribed. While an artists’ life and work do undergo a sort of transformation when they die, as indicated above, there is a more dangerous tactic of shaping an artists’ legacy to what someone believes in the aftermath. Of course there are successful attempts at this kind of posthumous study, but it’s not without risks. And this was the point of Morris’ work after all – his long-winded explanations of his work, sometimes included on the piece itself as in the Blind drawings, were only meant to serve as a decisive indication that description and visual art are always separated by an explanatory gap. In the same issue of Critical Inquiry that Davidson’s essay appeared in, Morris also published a text on the same body of work. But in Morris’ he wrote about both he and Davidson in the third person, continuing Davidson’s idea of triangulation: that the relationship between the viewer, the artist, and “the location of his creative acts” form an informative triangle. Davidson’s title rings true again, with Morris playing “The Third Man” in his own triangle between his work, Davidson the critic/collaborator, and himself the artist.

This began by saying I’m glad Morris is dead; I’ll elaborate. It’s an ambiguous kind of happiness. I’m glad that a fruitful art career has wrapped up positively. I’m glad that this great artist has stepped aside for the next generation of great artists to begin in earnest. I’m glad that he didn’t jump the shark. I’m not happy that a human being has died: I’m happy that someone I look up to has extinguished after a long life full of the pursuit of passion. His last solo exhibition at his long-time representation, Castelli Gallery, was titled Seeing As Is Not Saying That, which is another Davidson quote. Morris’ interests only intensified as he grew older, and while he would revisit forms and materials that he engaged as a younger artist, he made his pursuit something like truth in art. This is admirable. Older artists frequently dry up and just keep punching out the same works they always make, but Morris stayed true. ‘Seeing as’ really isn’t ‘saying that’, because the image we have of an artwork is more than the words can describe. But Morris was always willing to provide reasons for his work to the best of his ability, even knowing that they would never suffice as an explanation. Perhaps this is just a cautionary tale against interpretation of a specific kind. An artist and their audience provides everything necessary in their lifetime. Nobody needs revisionist evaluations by historians claiming ownership over the dead. Maybe related to this, I would like to close this obituary with a quote from Interview Magazine that Morris did with Wade Guyton. When Guyton asks Morris if he identifies negativity in his own work, he responds: “Yes, negativity is always hovering. I like W.H. Auden’s Quote, “Art is born of humiliation.” And let’s not forget good old hate.”

This began by saying I’m glad Morris is dead; I’ll elaborate. It’s an ambiguous kind of happiness. I’m glad that a fruitful art career has wrapped up positively. I’m glad that this great artist has stepped aside for the next generation of great artists to begin in earnest. I’m glad that he didn’t jump the shark. I’m not happy that a human being has died: I’m happy that someone I look up to has extinguished after a long life full of the pursuit of passion. His last solo exhibition at his long-time representation, Castelli Gallery, was titled Seeing As Is Not Saying That, which is another Davidson quote. Morris’ interests only intensified as he grew older, and while he would revisit forms and materials that he engaged as a younger artist, he made his pursuit something like truth in art. This is admirable. Older artists frequently dry up and just keep punching out the same works they always make, but Morris stayed true. ‘Seeing as’ really isn’t ‘saying that’, because the image we have of an artwork is more than the words can describe. But Morris was always willing to provide reasons for his work to the best of his ability, even knowing that they would never suffice as an explanation. Perhaps this is just a cautionary tale against interpretation of a specific kind. An artist and their audience provides everything necessary in their lifetime. Nobody needs revisionist evaluations by historians claiming ownership over the dead. Maybe related to this, I would like to close this obituary with a quote from Interview Magazine that Morris did with Wade Guyton. When Guyton asks Morris if he identifies negativity in his own work, he responds: “Yes, negativity is always hovering. I like W.H. Auden’s Quote, “Art is born of humiliation.” And let’s not forget good old hate.”