by Timothy Don

In my capacity as art editor at Lapham’s Quarterly, I’ve spent the last six weeks researching images for our upcoming issue on TRADE. It was not a thematic that excited me when I started, I have to admit—I’m a curator and a writer, not a businessman or an economist, dammit! But after looking at more than 10,000 paintings, sculptures, and photographs that limn the human urge to exchange goods, a faint thrill and a growing sense of despair have both begun to take root.I’ve peered into the faces of Ferdinand Bol’s Syndics of the Wine Traders Guild of Amsterdam from 1660, looking for signs of avarice, prudence, and rectitude.

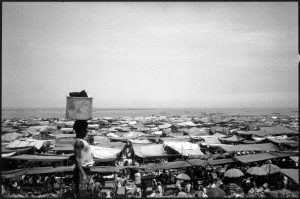

I’ve turned in my hands a 3rd century terracotta figurine of a camel carrying transport amphora (a secular, material expression of the nativity scene I just disassembled with my daughter). I’ve flipped through Alex Majoli’s 1999 series of photographs of the Roque Santeiro in Angola, the largest open-air market in Africa. According to Alex, the Roque attracts roughly one million people per day, and its vendors sell anything and everything: food, weapons, drugs, even people. It hosts church services and marriages. It shelters war cripples, homeless refugees, police, prostitutes, and the insane. Babies are born and the dead are interred within and beneath its stalls. At this “market of the damned,” Hieronymus Bosch’s 15th century visions of hell have been fully realized by the predations of 20th century capitalism.

A line and a theme have emerged through the iconography I’ve been following: to trade is human. We buy and we sell; we exchange, barter, haggle, negotiate, promise, vouchsafe, con, steal, acquire, and unload. It’s what we do; it’s what we’ve always done. The allure of trade lies not so much in the goods amassed as in the frisson of exchange: the contact with another human being that occurs in the act of trade. The slipping-ness from one to another. The handshake, the greased palm, the unctuous smile. The flow, the liquidity. The intimate bond that is established between two people when they make a deal. To trade is human. It’s dirty and oily and sexy.

And yet, underneath trade, there is something else going on. Something very faint, something very fragile, something that only adds to the excitement and the value of the goods on the table, is put at risk each time a trade is made. This something is trust. Read more »

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

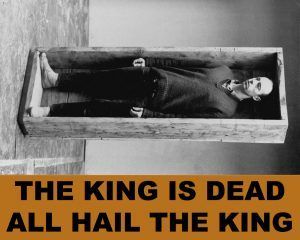

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.  JOHN MCDONNELL IS CAGEY

JOHN MCDONNELL IS CAGEY  Bellini was probably even younger than Mantegna when he first saw his new relative’s Presentation of Christ in the Temple – art historians will never stop worrying about his exact birthdate. (He may have been Jacopo Bellini’s illegitimate son. Records are scarce. Mantegna was the child of a carpenter, from a very ordinary village. His birthdate is also unknown.) When Bellini turned back to The Presentation of Christ in the Temple twenty years later he was the master of a new style, and dialogue with Mantegna had established itself as an aspect of that mastery – his great Agony in the Garden, done in response to a panel by his brother-in-law, lay behind him. It is hard, therefore, not to see the redoing of The Presentation of Christ in the Temple as some kind of contest as well as homage. But I found myself as I looked convinced that for Bellini what counted most was the opportunity, within the confines of someone else’s invention, to reflect on – to discover – what his own art most deeply consisted of. Oil paint versus tempera made many things clear. And, further, coming to terms with the true nature of one’s art – one’s necessary medium – meant coming closer to the mysteries enounced in Luke’s text.

Bellini was probably even younger than Mantegna when he first saw his new relative’s Presentation of Christ in the Temple – art historians will never stop worrying about his exact birthdate. (He may have been Jacopo Bellini’s illegitimate son. Records are scarce. Mantegna was the child of a carpenter, from a very ordinary village. His birthdate is also unknown.) When Bellini turned back to The Presentation of Christ in the Temple twenty years later he was the master of a new style, and dialogue with Mantegna had established itself as an aspect of that mastery – his great Agony in the Garden, done in response to a panel by his brother-in-law, lay behind him. It is hard, therefore, not to see the redoing of The Presentation of Christ in the Temple as some kind of contest as well as homage. But I found myself as I looked convinced that for Bellini what counted most was the opportunity, within the confines of someone else’s invention, to reflect on – to discover – what his own art most deeply consisted of. Oil paint versus tempera made many things clear. And, further, coming to terms with the true nature of one’s art – one’s necessary medium – meant coming closer to the mysteries enounced in Luke’s text. In Western democracies, literature no longer matters to politics. Once, literature and politics could co-exist on the same typewriter or in the same person: George Orwell in Britain, André Malraux in France. But that was a long time ago. Still, the powers of politics remain linguistic, whether bureaucratic or rhetorical: the war criminal at his desk, the elected representative on her Twitter. Amos Oz, the Israeli novelist who died today aged 79, was living proof of the political powers of literature. In Israel, which is a Western democracy most of the time, Oz is seen as a great writer but a failed politician. In the West, he is seen as the still-living conscience of a political failure. Nothing shows us both sides of a story so well as a novel. And nothing occludes the quality of literature like politics.

In Western democracies, literature no longer matters to politics. Once, literature and politics could co-exist on the same typewriter or in the same person: George Orwell in Britain, André Malraux in France. But that was a long time ago. Still, the powers of politics remain linguistic, whether bureaucratic or rhetorical: the war criminal at his desk, the elected representative on her Twitter. Amos Oz, the Israeli novelist who died today aged 79, was living proof of the political powers of literature. In Israel, which is a Western democracy most of the time, Oz is seen as a great writer but a failed politician. In the West, he is seen as the still-living conscience of a political failure. Nothing shows us both sides of a story so well as a novel. And nothing occludes the quality of literature like politics. Hans Rosling

Hans Rosling My parents’ generation, lucky enough to pass the biblical three score and 10, would describe themselves as living on “borrowed time.” Susan Gubar has been granted a longer credit line than most. In 2008, in her mid-60s, she learned she had ovarian cancer. It spread. After the cruelties of chemo, she was subjected to “debulking” — surgical evisceration. Gubar described the procedure unflinchingly in her 2012 book,

My parents’ generation, lucky enough to pass the biblical three score and 10, would describe themselves as living on “borrowed time.” Susan Gubar has been granted a longer credit line than most. In 2008, in her mid-60s, she learned she had ovarian cancer. It spread. After the cruelties of chemo, she was subjected to “debulking” — surgical evisceration. Gubar described the procedure unflinchingly in her 2012 book, Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo Rachel M. Cohen in The Intercept:

Rachel M. Cohen in The Intercept:

Joseph Stiglitz in Project Syndicate:

Joseph Stiglitz in Project Syndicate: Edmundson’s project is a religious (or spiritual) attempt to discover alternatives to the everyday world of late-modern capitalism. No dogma is involved, save the premise of the book itself: namely, that ideals matter profoundly, and we can discover and use them through reading great literature. This is, one might say, the religion of ideals, a holding space between pure secularity and traditional religion. Its sole purpose is to say that somethingmatters more than our petty concerns with self-advancement, and through openness to that something we might encounter ways of life worth living.

Edmundson’s project is a religious (or spiritual) attempt to discover alternatives to the everyday world of late-modern capitalism. No dogma is involved, save the premise of the book itself: namely, that ideals matter profoundly, and we can discover and use them through reading great literature. This is, one might say, the religion of ideals, a holding space between pure secularity and traditional religion. Its sole purpose is to say that somethingmatters more than our petty concerns with self-advancement, and through openness to that something we might encounter ways of life worth living. The Met’s permanent collection can tell you much about the Greeks and Romans, the Babylonians and the Assyrians, medieval Japan and the many dynasties of China, but it does not have as much to say about more marginal peoples. History, here, gathers at the center. If one wants to see peripheries, one must look for them. Wandering the galleries, one rarely get a sense of the vast mosaic of peoples who lived within and often long past those great empires of stone, paper, and capital. The presence of so many Armenian works, directly beside sculpture from Pergamon and Rome, offers an alternative view of history, one in which time eventually pulls down the mighty from their thrones and sometimes lifts up the lowly. The margins come into focus.

The Met’s permanent collection can tell you much about the Greeks and Romans, the Babylonians and the Assyrians, medieval Japan and the many dynasties of China, but it does not have as much to say about more marginal peoples. History, here, gathers at the center. If one wants to see peripheries, one must look for them. Wandering the galleries, one rarely get a sense of the vast mosaic of peoples who lived within and often long past those great empires of stone, paper, and capital. The presence of so many Armenian works, directly beside sculpture from Pergamon and Rome, offers an alternative view of history, one in which time eventually pulls down the mighty from their thrones and sometimes lifts up the lowly. The margins come into focus. Around 1730 Johann Sebastian Bach began to recycle his earlier works in a major way. He was in his mid-forties at the time, and he had composed hundreds of masterful keyboard, instrumental, and vocal pieces, including at least three annual cycles of approximately sixty cantatas each for worship services in Leipzig, where he was serving as St. Thomas Cantor and town music director. Bach was at the peak of his creative powers. Yet for some reason, instead of sitting down and writing original music, he turned increasingly to old compositions, pulling them off the shelf and using their contents as the basis for new works.

Around 1730 Johann Sebastian Bach began to recycle his earlier works in a major way. He was in his mid-forties at the time, and he had composed hundreds of masterful keyboard, instrumental, and vocal pieces, including at least three annual cycles of approximately sixty cantatas each for worship services in Leipzig, where he was serving as St. Thomas Cantor and town music director. Bach was at the peak of his creative powers. Yet for some reason, instead of sitting down and writing original music, he turned increasingly to old compositions, pulling them off the shelf and using their contents as the basis for new works.