by Samia Altaf

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Most of the time the female protagonists in our local films were uneducated but good, pious women seemingly knowing little of the world’s evil. They existed in a limited space, physically and mentally circumscribed by a patriarchal society, sheltered and protected by ‘their’ men and dependent on them for validation. They could cook up a storm, look after the household, sweep and clean, tend to animals and sick husbands, all in a day, without getting tired or complaining.

But they remained submissive women who suffered silently and deferred endlessly to their husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, and society. What would people say? What would make the family lose face? The family ‘honor’ was always tied to a woman’s behavior, to her desires, and no one was allowed to forget that. Conforming to those norms secured women a place in the community, credibility and status, and the more they suffered and sacrificed themselves the more they were lauded as role models. Such lessons were not lost on young girls and boys and went a long way in shaping expectations for their futures and standards of acceptable behavior. Read more »

Nearly forty years after his death in 1980, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre is best remembered as the father of existentialism. We are most familiar with him as the theorist of freedom, authenticity, and bad faith in philosophical treatises such as Being and Nothingness (1943) and literary works such as Nausea (1938) and No Exit (1944). But eclipsed in this popular image is an appreciation of the staggering range of his dozens of volumes of published work, especially the fruit of his political activity from the end of World War II until his death—a period marked most notably by a rich and sustained engagement with Marxism.

Nearly forty years after his death in 1980, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre is best remembered as the father of existentialism. We are most familiar with him as the theorist of freedom, authenticity, and bad faith in philosophical treatises such as Being and Nothingness (1943) and literary works such as Nausea (1938) and No Exit (1944). But eclipsed in this popular image is an appreciation of the staggering range of his dozens of volumes of published work, especially the fruit of his political activity from the end of World War II until his death—a period marked most notably by a rich and sustained engagement with Marxism. History records many examples of some person, tribe or nation taking an advantage based on better information than their rivals. Whether it is war, economic activity, love and romance or career the competitive edge leading to victory is enjoyed by those who possess the ability to extract and use information to increase the probability of their predicted outcomes. Use the word probability, forecasting, and prediction and thoughts start to wander, your mind has trouble gaining traction. Why is that?

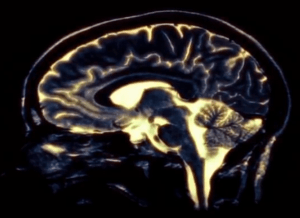

History records many examples of some person, tribe or nation taking an advantage based on better information than their rivals. Whether it is war, economic activity, love and romance or career the competitive edge leading to victory is enjoyed by those who possess the ability to extract and use information to increase the probability of their predicted outcomes. Use the word probability, forecasting, and prediction and thoughts start to wander, your mind has trouble gaining traction. Why is that? In November 2018, the world’s measurement experts are expected to revise the SI, this time approving a system that does not depend on physical objects. Instead, it’ll be based entirely on the speed of light and other “constants” of physical science, resulting in a measurement system that might truly and finally be for all times and for all people.

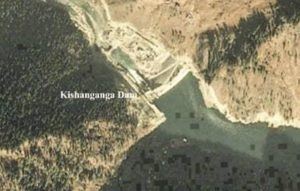

In November 2018, the world’s measurement experts are expected to revise the SI, this time approving a system that does not depend on physical objects. Instead, it’ll be based entirely on the speed of light and other “constants” of physical science, resulting in a measurement system that might truly and finally be for all times and for all people. Imagine a case involving the most sensitive issues of national security possible. Imagine that Pakistan wins a conclusive victory in that case. Now imagine that Pakistan wastes that victory and spends 5 years blundering about in a dead end. Kishanganga is that case.

Imagine a case involving the most sensitive issues of national security possible. Imagine that Pakistan wins a conclusive victory in that case. Now imagine that Pakistan wastes that victory and spends 5 years blundering about in a dead end. Kishanganga is that case. Debates over the extent to which racial attitudes and economic distress explain voting behavior in the 2016 election have tended to be limited in scope, focusing on the extent to which each factor explains white voters’ two-party vote choice. This limited scope obscures important ways in which these factors could have been related to voting behavior among other racial sub-groups of the electorate, as well as participation in the two-party contest in the first place. Using the vote-validated 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, merged with economic data at the ZIP code and county levels, we find that racial attitudes strongly explain two-party vote choice among white voters—in line with a growing body of literature. However, we also find that local economic distress was strongly associated with non-voting among people of color, complicating direct comparisons between racial and economic explanations of the 2016 election and cautioning against generalizations regarding causal emphasis.

Debates over the extent to which racial attitudes and economic distress explain voting behavior in the 2016 election have tended to be limited in scope, focusing on the extent to which each factor explains white voters’ two-party vote choice. This limited scope obscures important ways in which these factors could have been related to voting behavior among other racial sub-groups of the electorate, as well as participation in the two-party contest in the first place. Using the vote-validated 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, merged with economic data at the ZIP code and county levels, we find that racial attitudes strongly explain two-party vote choice among white voters—in line with a growing body of literature. However, we also find that local economic distress was strongly associated with non-voting among people of color, complicating direct comparisons between racial and economic explanations of the 2016 election and cautioning against generalizations regarding causal emphasis. Native Americans are only one percent of the population, but their images are on our boxes of butter and cornstarch. Their names are used to sell motorcycles and cars. And one of their brief encounters with English colonists is the basis of one of our biggest holidays. The story of Thanksgiving definitely evolved over time. The First Thanksgiving of 1621 happened but with little notice or attention. Curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian like to call it “a brunch in the forest.” Yes, it took place between Native Americans and Pilgrims. But the event was not exempt from history’s subjectivity. “What historians have had trouble explaining to civilians is that history is always a narrative. It always has a level of fiction in it,” says the Smithsonian’s Paul Chaat Smith. “That’s why the term ‘revisionist’ never really works,” he adds. “Because all history changes over time.” Smith is a co-curator of the National Museum of the American Indian’s highly acclaimed exhibition

Native Americans are only one percent of the population, but their images are on our boxes of butter and cornstarch. Their names are used to sell motorcycles and cars. And one of their brief encounters with English colonists is the basis of one of our biggest holidays. The story of Thanksgiving definitely evolved over time. The First Thanksgiving of 1621 happened but with little notice or attention. Curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian like to call it “a brunch in the forest.” Yes, it took place between Native Americans and Pilgrims. But the event was not exempt from history’s subjectivity. “What historians have had trouble explaining to civilians is that history is always a narrative. It always has a level of fiction in it,” says the Smithsonian’s Paul Chaat Smith. “That’s why the term ‘revisionist’ never really works,” he adds. “Because all history changes over time.” Smith is a co-curator of the National Museum of the American Indian’s highly acclaimed exhibition  For the microbiologist Justin Sonnenburg, that career-defining moment—the discovery that changed the trajectory of his research, inspiring him to study how diet and native microbes shape our risk for disease—came from a village in the African hinterlands. A group of Italian microbiologists had compared the intestinal microbes of young villagers in Burkina Faso with those of children in Florence, Italy. The villagers, who subsisted on a diet of mostly millet and sorghum, harbored far more microbial diversity than the Florentines, who ate a variant of the refined, Western diet. Where the Florentine microbial community was adapted to protein, fats, and simple sugars, the Burkina Faso microbiome was oriented toward degrading the complex plant carbohydrates we call fiber.

For the microbiologist Justin Sonnenburg, that career-defining moment—the discovery that changed the trajectory of his research, inspiring him to study how diet and native microbes shape our risk for disease—came from a village in the African hinterlands. A group of Italian microbiologists had compared the intestinal microbes of young villagers in Burkina Faso with those of children in Florence, Italy. The villagers, who subsisted on a diet of mostly millet and sorghum, harbored far more microbial diversity than the Florentines, who ate a variant of the refined, Western diet. Where the Florentine microbial community was adapted to protein, fats, and simple sugars, the Burkina Faso microbiome was oriented toward degrading the complex plant carbohydrates we call fiber. The discussion of Islam in world politics in recent years has tended to focus on how religion inspires or is used by a wide range of social movements, political parties, and militant groups. Less attention has been paid, however, to the question of how governments—particularly those in the Middle East—have incorporated Islam into their broader foreign policy conduct. Whether it is state support for transnational religious propagation, the promotion of religious interpretations that ensure regime survival, or competing visions of global religious leadership; these all embody what we term in this new report the “geopolitics of religious soft power.”

The discussion of Islam in world politics in recent years has tended to focus on how religion inspires or is used by a wide range of social movements, political parties, and militant groups. Less attention has been paid, however, to the question of how governments—particularly those in the Middle East—have incorporated Islam into their broader foreign policy conduct. Whether it is state support for transnational religious propagation, the promotion of religious interpretations that ensure regime survival, or competing visions of global religious leadership; these all embody what we term in this new report the “geopolitics of religious soft power.”

The share of Americans who say sex between unmarried adults is “not wrong at all” is at an all-time high. New cases of HIV are at an all-time low. Most women can—at last—get birth control for free, and the morning-after pill without a prescription.

The share of Americans who say sex between unmarried adults is “not wrong at all” is at an all-time high. New cases of HIV are at an all-time low. Most women can—at last—get birth control for free, and the morning-after pill without a prescription. At the chilling climax of William S. Lind’s 2014 novel “Victoria,” knights wearing crusader’s crosses and singing Christian hymns brutally slay the politically correct faculty at Dartmouth College, the main character’s (and Mr. Lind’s) alma mater. “The work of slaughter went quickly,” the narrator says. “In less than five minutes of screams, shrieks and howls, it was all over. The floor ran deep with the bowels of cultural Marxism.”

At the chilling climax of William S. Lind’s 2014 novel “Victoria,” knights wearing crusader’s crosses and singing Christian hymns brutally slay the politically correct faculty at Dartmouth College, the main character’s (and Mr. Lind’s) alma mater. “The work of slaughter went quickly,” the narrator says. “In less than five minutes of screams, shrieks and howls, it was all over. The floor ran deep with the bowels of cultural Marxism.” When I first read Marguerite Duras’s Moderato Cantabile for my high school AP French class, an alarm went off on me. That I was reading the words of someone who understood love in the same way I did. At that point in my life I hadn’t yet experienced love, but it didn’t matter. It was a foreshadowing of what was to come, of what I already knew to be true. The next year, in a college French class, I read Duras’s The Lover. From the first page (J’ai un visage détruit) I saw myself again. I felt recognized. But even as I was, in Kate Briggs’s words, underlining, typing the passage out, capturing it on my phone…even in its plenitude, even as it is right now filling me up, there is, I feel, something missing. What is missing is me: my action, my further activity…the audacious counteraction—of the active force that is me. Perhaps in reading these words, the ache that opened up in me was not from identification but from feeling that this writing wouldn’t be complete until I had acted my own force on it. The drive to translate—not for glory, not for recognition, not for money (obviously): to complete the text (in my eyes) by adding my own force to it. When I read a given book and feel the jolt Briggs describes as a matter of intensely felt identification, it’s not the text, it’s me in the text. In the words of Duras (in our translation of her), What moves me is myself.

When I first read Marguerite Duras’s Moderato Cantabile for my high school AP French class, an alarm went off on me. That I was reading the words of someone who understood love in the same way I did. At that point in my life I hadn’t yet experienced love, but it didn’t matter. It was a foreshadowing of what was to come, of what I already knew to be true. The next year, in a college French class, I read Duras’s The Lover. From the first page (J’ai un visage détruit) I saw myself again. I felt recognized. But even as I was, in Kate Briggs’s words, underlining, typing the passage out, capturing it on my phone…even in its plenitude, even as it is right now filling me up, there is, I feel, something missing. What is missing is me: my action, my further activity…the audacious counteraction—of the active force that is me. Perhaps in reading these words, the ache that opened up in me was not from identification but from feeling that this writing wouldn’t be complete until I had acted my own force on it. The drive to translate—not for glory, not for recognition, not for money (obviously): to complete the text (in my eyes) by adding my own force to it. When I read a given book and feel the jolt Briggs describes as a matter of intensely felt identification, it’s not the text, it’s me in the text. In the words of Duras (in our translation of her), What moves me is myself. This is also a musical biography that makes clear why, after all, we should bother to read a book about Chopin. Far from being a salon miniaturist, he was a major artist, a true heir to Bach and Mozart (as well as Beethoven, though he wouldn’t have liked it said), a creator of new forms, new modes of expression, and new keyboard techniques and sonorities. Walker rightly indicates Scriabin and Fauré as direct musical descendants, and Debussy as heir to Chopin’s discoveries about the piano; and since Debussy drew a new language partly from these findings, Walker might well have claimed (though he doesn’t) that Chopin lies behind a good deal of modern music, too. How’s that for a salon miniaturist?

This is also a musical biography that makes clear why, after all, we should bother to read a book about Chopin. Far from being a salon miniaturist, he was a major artist, a true heir to Bach and Mozart (as well as Beethoven, though he wouldn’t have liked it said), a creator of new forms, new modes of expression, and new keyboard techniques and sonorities. Walker rightly indicates Scriabin and Fauré as direct musical descendants, and Debussy as heir to Chopin’s discoveries about the piano; and since Debussy drew a new language partly from these findings, Walker might well have claimed (though he doesn’t) that Chopin lies behind a good deal of modern music, too. How’s that for a salon miniaturist? William H. Gass loved words. “A word is a wanderer,” he wrote in “Carrots, Noses, Snow, Rose, Roses.” “Except in the most general syntactical sense, it has no home.”

William H. Gass loved words. “A word is a wanderer,” he wrote in “Carrots, Noses, Snow, Rose, Roses.” “Except in the most general syntactical sense, it has no home.”