Kelly and Zach Weinersmith in Delancyplace:

Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment.

Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment.

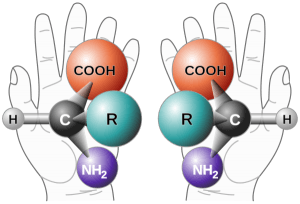

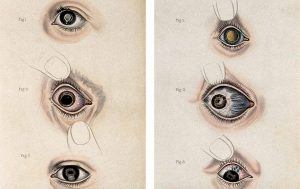

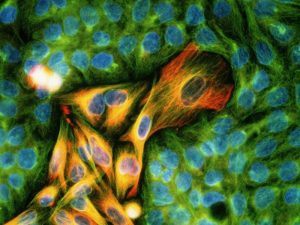

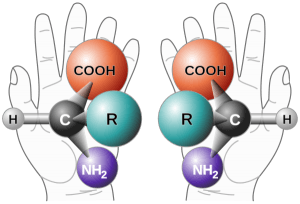

“Life is made of lots of little molecules, and these molecules make up important bigger molecules, like DNA, RNA, and proteins. Some molecules exhibit what is called chirality, from the Greek word for ‘hand.’ If a molecule has chirality that basically means there is a mirror version of it. “To wrap your head around ‘mirror versions’ of things, think about your hands. They look exactly the same, but no matter how you rotate your left hand, it won’t be exactly the same as the right. If you have your palms up, your left thumb will point left and your right thumb will point right. Each hand has all the same parts, but they are flipped, as if through a mirror. “When you have two molecules that are mirror images of one another, one of these molecules is designated as the left-handed version and the other as the right-handed version. Intriguingly, life seems to favor a certain handedness for particular tasks. For example, almost all amino acids (which you may remember from previous chapters are the building blocks of proteins) are in the left-handed form. Why nature abhors right-handed amino acids is a topic of debate, but even the amino acids we find in space tend to be left-handed.

“But screw nature. Whatever her reasoning is, there is no known physical reason we couldn’t create an organism out of completely opposite-handed molecules in the lab — a ‘mirror organism,’ if you like. Some scientists, including Dr. [George] Church [of Harvard], are working to create (simple) mirror organisms, with the hope creating larger and larger such creatures. Why exactly would we want this? Well, for one, it’s awesome. You create something that looks like a nice little kitty, but is totally incompatible with the rest of the life on the planet, perhaps even the universe. For example, mirror-opposite organisms would need to eat mirror food in order to be able to digest it. They would also be undigestible to all predators. Best of all, a mirror-opposite organism would be completely immune to all diseases, because all living parasites and pathogens evolved to infect organisms with normal chirality.

“And if it worked, hey, we could scale up to making mirror-opposite humans.

More here.

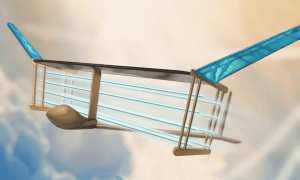

The first ever “solid state” plane, with no moving parts in its propulsion system, has successfully flown for a distance of 60 metres, proving that heavier-than-air flight is possible without jets or propellers.

The first ever “solid state” plane, with no moving parts in its propulsion system, has successfully flown for a distance of 60 metres, proving that heavier-than-air flight is possible without jets or propellers.

During nine years as dean of Harvard Medical School, I enthusiastically supported efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion. Two years after leaving that role, I recently

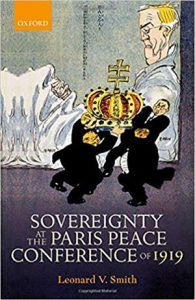

During nine years as dean of Harvard Medical School, I enthusiastically supported efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion. Two years after leaving that role, I recently  The 1815 Congress of Vienna was the most important diplomatic encounter of the 19th century. When a Parisian court painter called Jean-Baptiste Isabey depicted the scene, most of the figures around the conference table were aristocrats. Fast forward to its closest 20th-century equivalent — the Paris Peace Conference, convened at the end of the first world war: barely half a dozen out of more than 60 delegates had titles, and of these one was a recent baronet and another a maharajah.

The 1815 Congress of Vienna was the most important diplomatic encounter of the 19th century. When a Parisian court painter called Jean-Baptiste Isabey depicted the scene, most of the figures around the conference table were aristocrats. Fast forward to its closest 20th-century equivalent — the Paris Peace Conference, convened at the end of the first world war: barely half a dozen out of more than 60 delegates had titles, and of these one was a recent baronet and another a maharajah. The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that.

The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that. There’s a verbal tic particular to a certain kind of response to a certain kind of story about the thinness and desperation of American society; about the person who died of preventable illness or the Kickstarter campaign to help another who can’t afford cancer treatment even with “good” insurance; about the plight of the homeless or the lack of resources for the rural poor; about underpaid teachers spending thousands of dollars of their own money for the most basic classroom supplies; about train derailments, the ruination of the New York subway system and the decrepit states of our airports and ports of entry.

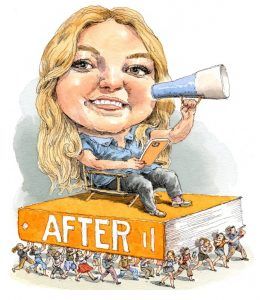

There’s a verbal tic particular to a certain kind of response to a certain kind of story about the thinness and desperation of American society; about the person who died of preventable illness or the Kickstarter campaign to help another who can’t afford cancer treatment even with “good” insurance; about the plight of the homeless or the lack of resources for the rural poor; about underpaid teachers spending thousands of dollars of their own money for the most basic classroom supplies; about train derailments, the ruination of the New York subway system and the decrepit states of our airports and ports of entry. If anyone is entitled to misgivings about the pernicious world of publishing, it’s Helen DeWitt, the long-suffering veteran of a by-now-well-known bevy of artistic successes and commercial failures. The Last Samurai, an exuberantly experimental novel about a child prodigy and his brilliant but depressive mother, made a triumphant debut at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1999, but its publication was fraught. DeWitt fought to retain her idiosyncratic typesetting, faced off with a belligerent copy editor, and saw few profits in the wake of financial disputes with her publisher. Worse still, the imprint responsible for The Last Samurai folded in 2005. Though the book commanded a dedicated cult following, it went out of print until New Directions reissued it 11 years later.

If anyone is entitled to misgivings about the pernicious world of publishing, it’s Helen DeWitt, the long-suffering veteran of a by-now-well-known bevy of artistic successes and commercial failures. The Last Samurai, an exuberantly experimental novel about a child prodigy and his brilliant but depressive mother, made a triumphant debut at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1999, but its publication was fraught. DeWitt fought to retain her idiosyncratic typesetting, faced off with a belligerent copy editor, and saw few profits in the wake of financial disputes with her publisher. Worse still, the imprint responsible for The Last Samurai folded in 2005. Though the book commanded a dedicated cult following, it went out of print until New Directions reissued it 11 years later. Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536. In Europe, “It was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year,” says McCormick, a historian and archaeologist who chairs the Harvard University Initiative for the Science of the Human Past.

Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536. In Europe, “It was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year,” says McCormick, a historian and archaeologist who chairs the Harvard University Initiative for the Science of the Human Past. I’ve never cried to “We Are The Champions.”

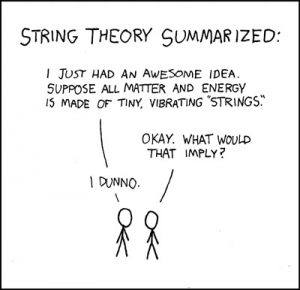

I’ve never cried to “We Are The Champions.” Way back in 1996 science writer John Horgan published The End of Science, in which he made the argument that various fields of science were running up against obstacles to any further progress of the magnitude they had previously experienced. One can argue about other fields (please don’t do it here…), but for the field of theoretical high energy physics, Horgan had a good case then, one that has become stronger and stronger as time goes on.

Way back in 1996 science writer John Horgan published The End of Science, in which he made the argument that various fields of science were running up against obstacles to any further progress of the magnitude they had previously experienced. One can argue about other fields (please don’t do it here…), but for the field of theoretical high energy physics, Horgan had a good case then, one that has become stronger and stronger as time goes on. Among the string of resignations triggered by the draft Brexit agreement with the European Union (EU), one stood out. In a double whammy for an embattled Prime Minister, Rehman Chishti the MP for Gillingham and Rainham resigned as both Vice Chairman of the Conservative Party as well as the PM’s Trade Envoy to Pakistan. Aside from citing Theresa May’s shambolic handling of Brexit negotiations,

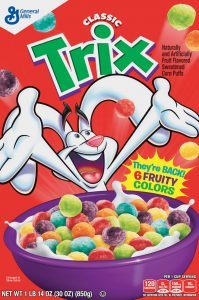

Among the string of resignations triggered by the draft Brexit agreement with the European Union (EU), one stood out. In a double whammy for an embattled Prime Minister, Rehman Chishti the MP for Gillingham and Rainham resigned as both Vice Chairman of the Conservative Party as well as the PM’s Trade Envoy to Pakistan. Aside from citing Theresa May’s shambolic handling of Brexit negotiations,  In 2015, General Mills reformulated Trix with “natural” colors. Customers complained that the bright hues of their childhood cereal were now dull yellows and purples. Two years later, the company released Classic Trix to stand on store shelves alongside so-called No, No, No Trix, the natural version. This nickname, promising “no tricks,” sounds abstemious; the virtuous customer says no to technicolor temptation. But Trix customers wanted their colors back. As one Tweet put it: “I mean, I get that artificial flavors are bad and all that shiz, but man I miss neon colored Trix.”

In 2015, General Mills reformulated Trix with “natural” colors. Customers complained that the bright hues of their childhood cereal were now dull yellows and purples. Two years later, the company released Classic Trix to stand on store shelves alongside so-called No, No, No Trix, the natural version. This nickname, promising “no tricks,” sounds abstemious; the virtuous customer says no to technicolor temptation. But Trix customers wanted their colors back. As one Tweet put it: “I mean, I get that artificial flavors are bad and all that shiz, but man I miss neon colored Trix.” The line of French painting that stretches from Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People to Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (or from Camille Corot early in the 1820s to Henri Matisse on the eve of the First World War) is a unique episode in recent history. It has established itself as “world-historical,” to borrow a term from G. W. F. Hegel. That is, it continues to speak to aspects—distinctive features—of the modern condition which succeeding ages seem unable to bring into focus, or go on valuing and properly criticizing, without its aid. The tradition’s only rival, if this is the standard, may be German music from Johann Sebastian Bach to Richard Wagner.

The line of French painting that stretches from Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People to Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (or from Camille Corot early in the 1820s to Henri Matisse on the eve of the First World War) is a unique episode in recent history. It has established itself as “world-historical,” to borrow a term from G. W. F. Hegel. That is, it continues to speak to aspects—distinctive features—of the modern condition which succeeding ages seem unable to bring into focus, or go on valuing and properly criticizing, without its aid. The tradition’s only rival, if this is the standard, may be German music from Johann Sebastian Bach to Richard Wagner. Timbaland and Elliott developed a grammar, collecting extra-musical noises—sighs, women giggling, coughs, babies gurgling—and stacking them so that they became instruments in and of themselves. They weren’t afraid to experiment with sounds that were nearer to the grotesque than the beautiful. One of the most well known is the

Timbaland and Elliott developed a grammar, collecting extra-musical noises—sighs, women giggling, coughs, babies gurgling—and stacking them so that they became instruments in and of themselves. They weren’t afraid to experiment with sounds that were nearer to the grotesque than the beautiful. One of the most well known is the  The stunning failure of a once-promising cancer drug has got some researchers arguing that the field has moved too fast in its embrace of therapies that unleash the immune system. The drug, epacadostat,

The stunning failure of a once-promising cancer drug has got some researchers arguing that the field has moved too fast in its embrace of therapies that unleash the immune system. The drug, epacadostat,  Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment.

Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment. One afternoon in

One afternoon in