by Bill Benzon

“We’re in one of those great historic periods…when people don’t understand the world anymore…when the past is not sufficient to explain the future.”

–Peter Drucker

Fasten your seatbelts, we’re going for a ride. We start over 300 million years ago and arrive at the present in a mere six paragraphs. We remain here for the rest of the tour, looking at pictures and talking about a strange urban paradise situated in the middle of one of the most densely populated areas on the planet.

From Pangea to Hurricane Sandy

Roughly 335 million years ago, during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras, the Earth’s existing continental masses formed themselves into the supercontinent Pangea. Pangea began to breakup roughly 175 million years ago giving rise to the Palisades Sill, most visible as a series of cliffs running 50 miles along the west bank of the Hudson River in New York and New Jersey. The Palisades tapers down to sea level in what is now Jersey City.

Roughly 14,000 years ago the first humans settled in North America, spreading quickly across the continent and south through Central to South America. In 1609 the Lenape greeted Henry Hudson when he set foot in that area on his search for a Northwest Passage to China. Two centuries later railroads began emerging in North America. In the second quarter of the 19th Century and Camden and Amboy Railroad became the first in New Jersey, completing its first line in 1834. In the middle of the century the Erie and the Delaware-Lackawanna railroads completed the Long Dock Tunnel in 1861. It conveyed freight trains from the Meadowlands through the Palisades Sill to freight terminals on the Hudson River. By the early 20th century Jersey City had become a bustling port.

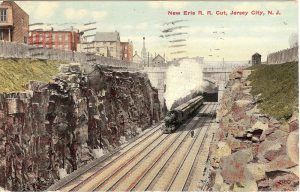

In 1906 the Erie Railroad began blasting a cut through the Palisades less than a football field’s width south of the Long Dock Tunnel. The Erie Cut was completed in 1910. It is between, say, 50 and 80 feet deep and 70 to 100 feet wide at the bottom. In four places the cut becomes short tunnels so that roads and buildings could go atop it; short bridges cross the cut at three other points. Collectively these are the Bergen Arches, the name by which this feature is known today.

Four railroad tracks were laid in it. They went to the Hudson river just yards south of the Holland Tunnel where they fed one of the world’s largest train terminals. Then, in the third quarter of the century, container ships were introduced and the freight facilities shifted to Newark Bay. Jersey City’s docks became useless, and so were the railroad lines that fed them. The last train went through the Arches in 1957. Three of the four tracks were ripped out of the cut and the eastern end was filled with dirt and rock.

In 2012 Hurricane Sandy ripped through the New York City area in late October. Costal areas of Jersey City were flooded and power was out in much of the city. Some areas were black for only a few days, others didn’t get power for weeks.

“What”, you may ask, “does this have to do with the Bergen Arches?” “Isn’t it obvious,” I respond, “the climate.” “The climate?”

Yes, the climate. While Hurricane Sandy is not directly attributable to global warming, it is widely believed that global warming now has broad effects on the climate. One of those effects is an increase in the activity the sends hurricanes up the East Coast of the United States. Those trains that ran through the Erie Cut, they burned carbon-based fuels, first coal, then diesel oil. They belong to the Industrial Age that inadvertently has created our emerging climate chaos. So, yes, there is an intimate, yet also indirect, relationship between the Bergen Arches and Hurricane Sandy.

The Bergen Arches and Jersey City

The Bergen Arches/Erie Cut is all but abandoned. People throw trash over the edge, homeless people build huts, and graffiti writers paint on the walls. It is a strange urban paradise. No one goes down there except graffiti writers, historic preservationists, photographers, and other assorted miscreants and adventurers.

Once you’re in the cut you’re in another world. Yes, New York City is two or three miles to the east across the Hudson and Jersey City is all over the place 85 feet up. But down in the cut, those places aren’t real. The Arches is its own world, lush vegetation, crumbling masonry, rusting rails, trash strewn about here and there, mud and muck, and mosquitoes, those damn mosquitoes! Nope, it’s not Machu Pichu and it’s not Victoria Falls, but it’s pretty damn good for being in the middle of one of the densest urban areas in the freakin’ civilized world.

When you’re down there you feel profoundly isolated from the city, more so than when you are in New York City’s Central Park, for example. But watch your feet. The ground is not level. Someone stuck a bunch of tires in the path, so you have to step around or through them, whatever’s your pleasure. In awhile it’s going to get swampy. Now you have to THINK about where you’re stepping. Sure, in your mind you’re rescuing the Pelucid Prince, or Princess, searching for the Knitting Needles of Fate, riding the Dragons of Xanadu over the Mountains of Bergensfjord. While your fancy’s flying, your feet have to decide whether or not to walk straight ahead where the water floats an inch deep over an inch and a half of mud. Or do you swerve to the left, up on the tracks, where it’s not so wet, but you have to fight thorn bushes and low-riding branches? Tough decisions for the Masked Redeemer of Chilltown (as the city is known in certain neighborhoods).

What, if anything, is Jersey City going to do with this forgotten paradise?

Nature? Culture? Graffiti – It’s what humans do

Thinking abstractly now, one might consider allowing the land revert to its natural state. After all, the city’s gotten along without them for over half a century. Why not just let nature take its course?

And that’s what has happened. As always, life has moved in and flourished. Forget any idea of letting this land revert to its ‘natural’ state. If by that you mean what it was before humans came in and changed things, well, then its natural state is solid rock. The stone that came out of that trench has long since been dispersed; it’s not coming back. Replacing it with new fill would not be an act of restoration, it would just be another human intervention, one that would destroy the life that’s now taken over the cut.

And, as I’ve indicated, humans have never fully abandoned the cut. We still go down there in ones, twos, and threes. Moreover at least twice in the last decade the cut has been used as an access and staging area for construction projects. No, we created the cut, used it in one way for half a century, and then we retreated, but still retained a residual presence while other creatures, mostly plants, bacteria, insects, some birds and I don’t know what else, took over.

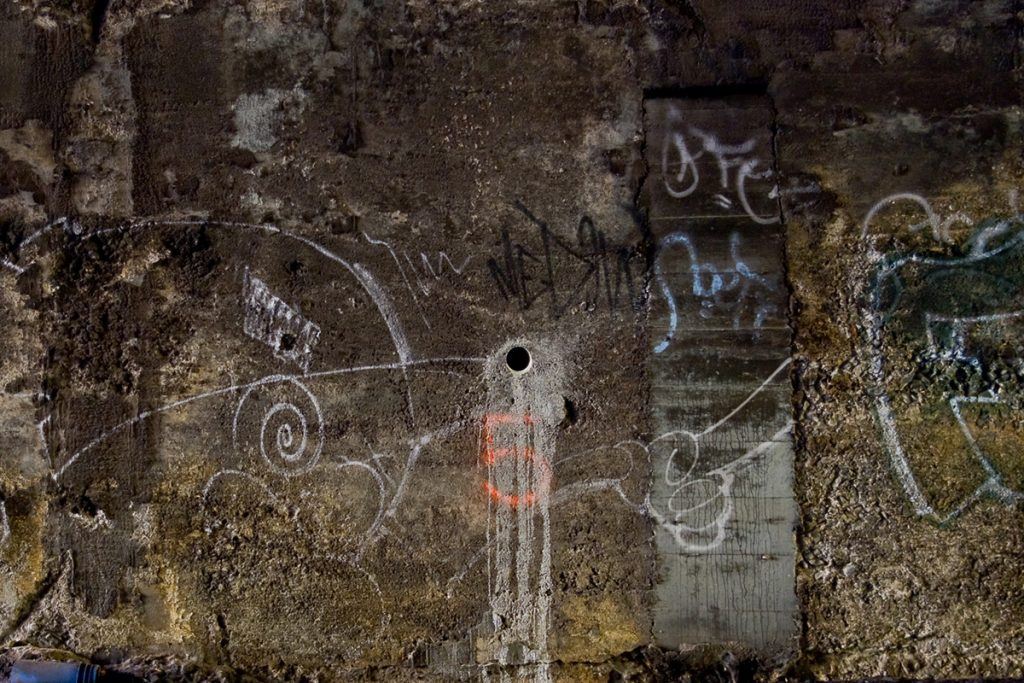

For the last twenty years, if not longer, graffiti writers (that’s what they call themselves, it’s about writing names, tags) have graced the walls. Which makes sense. Graffiti got started in the 1970s and 1980s across the river in New York City. Writers would use subway cars, inside and out, as their canvases. Of course, many folks did not approve. War broke out between the writers and the officials and good citizens of the city. Once writers knew their work would be ‘buffed’ sooner or later, they got used to its ephemeral nature. Not for them the long Parmenidian swings for the fences of the legit art world. They embraced Heraclitean flux and went with the flow. All things must pass, even a slammin’ burner.

Exposed to the weather above and seeping water below, the graffiti fades and ages, gradually disappearing into the rock or masonry on which it has been deposited.

Some of it feels like ancient markings in caves or on cliffs, which after all was one of the first if not the first forms of visual art.

And some graffiti disappears into the vegetation.

You tell me, where do we draw the line between nature and culture, between humans and other creatures? As you ponder this, remember where and when we are. We are in the Anthropocene era, which, my dictionary tells me, is “the current geological age, viewed as the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.” Where are we?

We are in the Erie Cut, under the Bergen Arches. And just why did we cut the earth like this? To provide passage for locomotives sending carbon dioxide into the are. The Anthropocene is the cumulative effect of hundreds of thousands of carbon dioxide belching engines of all shapes and sizes, serving tens of thousands of purposes. We are this land, we are this cut, we are natural creatures, these plants, these designs, we are in them and they in us.

How do we respond to – be responsible for one another?

What’s next?

Back in 2001 a long-time Jersey City activist, Dan Levin, and a local historian, John Gomez, got the Arches designated as an Endangered Site with Preservation New Jersey. A couple years later the New Jersey Department of Transportation and Parsons Brinkerhoff conduct a study of possible uses for the cut: light rail, automobile, biking? But nothing has been done and, as far as I know, nothing has yet been planned. The cut just lies there, at one and the same time both teeming with life and empty and forgotten.

One of the things Gomez and Levin had in mind was to link the Bergen Arches with the East Coast Greenway, a hiking and biking trail stretching from Maine to Florida along the East Coast, much like the Appalachian Trail goes through the Appalachians from Georgia to Main. More recently, the Crossroads Initiative, composed of various activists in Jersey City and the surrounding area, has been assembling a regional network of trails that would link with the Greenway. All these trails are based on unused transportation infrastructure and converge on the Bergen Arches.

The Bergen Arches, in turn, is a quarter of a mile or so north of another piece of abandoned railroad infrastructure, the Sixth Street Embankment.

Like the Arches, the Embankment conveyed four railroad lines to the Hudson River. It too was abandoned in mid-century and life has moved in, even as the city itself seems to disappear:

There is yet another piece of abandoned infrastructure that extends between the Embankment and the Arches:

What if we could connect these three pieces of abandoned rail line into one continuous two-and-a-half mile trail bisecting Jersey City from the banks of the Hudson on the East to the Meadowlands on the West?

This is a satellite view, with the yellow line indicating this trail:

You see the Embankment down there at the bottom and the Arches running diagonally from the center to the upper left.

This is the only continuous route across Hudson County by which that emerging regional network of trails can connect to the Hudson River and Liberty State Park. “Jersey City is in a unique position”, says Sean Gallagher, Director of Sustainable Design at Diller Scofidio + Renfro and a board member of the Embankment Preservation Coalition, “I don’t believe another city in the world has at this scale a potentially un-interrupted public and ecological corridor within the heart of its urban fabric. While New York City has the High Line that is above ground, and the proposed Low Line that is below ground, Jersey City could have both of these things linked together with a more robust geography and landscape that links to the United States East Coast Greenway. This city has the opportunity to demonstrate global leadership of how emerging green infrastructure can utilize its industrial roots for a safer, healthier urban community.”

The Bergen Arches, leading Jersey City back to the future – has a ring to it. Let’s go.

* * * * *

Full Disclosure: I am not a disinterested observer and chronicler of the Arches. Along with Greg Edgell I am co-founder of Bergen Arches, a NJ Nonprofit Corporation [501(c)3]. Here’s a link to our website: https://www.bergenarches.com/.