Zeal Greenberg is one of the most amazing men I’ve ever worked with. I emphasize “worked with”.

I’ve discussed Disney’s Fantasia and Fantasia 2000 over dinner with Steve Martin. I took Malcolm Forbes’s photo with one of his fans, who then took a photo of me and Forbes. He and his motorcycle club, the Capitalist Tools, were at the Americade rally in Lake George on July 4th weekend. And I once told Sheldon Glashow (physics Nobel 1979) I thought that physicists’ search for a “theory of everything” was ill-conceived and a bit hubristic – I didn’t see that their theory of everything would help much with the problems that most interested me. Unfortunately the meeting we were attending started before I was able to explain myself and, alas, we didn’t get back together afterward.

I didn’t WORK with these folks.

Met them, chatted with them, but I never collaborated with them on a common project. I worked closely with Zeal for years early in the millennium.

I’m tempted to say that you couldn’t imagine a stranger and more unlikely pair. But that’s not true. Of course you could. But still… I’m a Ph. D. and rather Old School WASP in my sense of self-presentation. Zeal never went to college, started out as a schmatta salesman, and lives and breathes sales and marketing. But we had a common desire, to change the world. I was happy to help him pursue his vision.

It was a dark and rainy night

It didn’t start out that way. I wanted him to hire me as a consultant. Yes, he had a wonder vision. But I needed money.

It was a nasty rainy November evening in 2003 or 2004 and I was sitting in the lobby of the Faculty House at Columbia University. I was there for the monthly meeting of the University Seminar on Computers, Man, and Society. We’d gather in the lobby to chat and have a drink or two, then go up to the dining room for our meal. Afterward we’d repair to a meeting room for the month’s presentation and discussion.

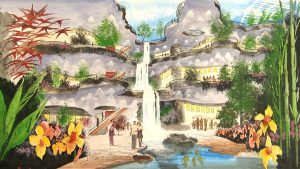

I was sipping my scotch and merrily chatting with whomever when Takishi Utsumi, another member of the seminar, walked in with a guest, Jerry Greenberg. Jerry – he didn’t call himself “Zeal” until several years later – was the head of The World Endowment Development Foundation (quite a mouthful, that). He proposed to transform Governors Island, a 172 acre former Coast Guard base in New York Harbor, into World Island, which he described as a “permanent world’s fair for a world that’s permanently fair”. Think of it as a combination of the best features of the United Nations, Disney World, a kid’s rumpus room, the trading floor at the Chicago Board of Trade, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the Japanese exhibit at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. (Wow!) It would cost $25 billion or so (Wow wow woW!) and be planted with orchids. (I’m likin’ this guy…) Why orchids? Beauty aside, they’re an early warning system for climate change, when the orchids go, we’re not going to be far behind. (…a lot!)

Hmmmm…the man’s got the soul of a poet…the project’s crazy expensive…if he’s going after it he MUST have money, no? I wonder if he needs some consulting help?

We met at his Manhattan office on Fifth Avenue just off of Union Square. I walked through the door. Whoops! It didn’t look good. The room was large and clean, but old and a bit battered. Not the Class A office space of a rich man determined to change the world as his last act. Perhaps he’s eccentric? Well, of course he’s eccentric. A permanent world’s fair for a world that’s permanently fair? Orchids? On 172 acres in New York Harbor?

Jerry was the only one there. He greeted me. We sat down. Table was piled with stuff. He began rambling his way through his spiel. Governors Island had been a Coast Guard base until the end of the century. Senator Moynihan convinced the government to was sell the island to GIPEC (Governors Island Preservation and Education Corporation), jointly owned by New York State and New York City. GIPEC took possession for a couple dollars rather than a price at market rate. Can you imagine the market rate for a 172 acres of developable property in New York Harbor?

There was a catch. Since the Feds gave the island away, it had to be used for the pubic good. In particular there could be no gambling on the island, no permanent residences, and the northern half was historically landmarked and so had to be preserved. GIPEC was accepting proposals for the non-profit development of the island, with the developer coming up with the money. All of it. In the case of Jerry’s World Island scheme, 25 billion simoleons.

Jerry didn’t know where money was coming from. But the opportunity was too rich. He had to go for it.

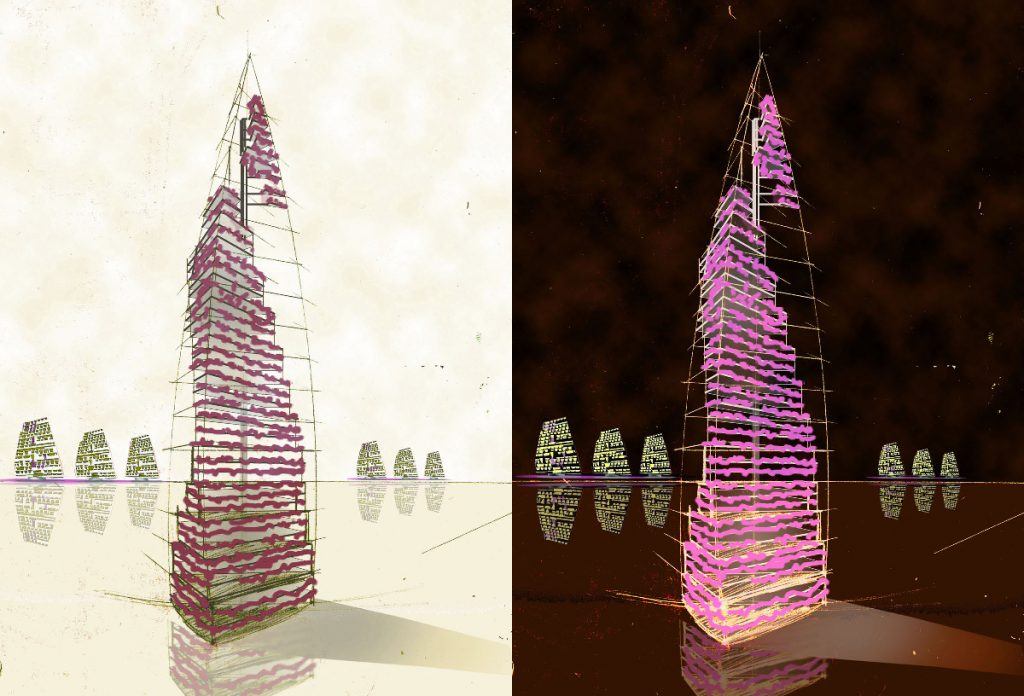

Others believed in him. There were signs. He showed me a handsome book describing the project. An inch thick. I judged it to be five-figures worth of NYC graphic design talent. There was another five-figures worth of CGI renderings of the proposed buildings (courtesy of Skanska, the Swedish construction firm). Jerry’s team used to hold meetings at Lehman Brothers until, something happened, whatever. (Remember, this was before Lehman Brothers disappeared into a tornado of financial sorcery in 2008.)

I asked about money. He’d been obviously been asked this before. He was ready: “deferred compensation.” I didn’t laugh. I signed on. I liked the guy. I liked the project. Life’s too short.

They all listened

And so we began. Jerry didn’t have much in the way of computer skills. Someone had done a bare bones PowerPoint presentation which he’d printed out and used as a briefing book. I created a presentation worthy of the project. Heck, I did three, four, five, eleventy presentations. We went on a GIPEC tour of Governors Island.

I met people. Bob Silverman, the Turner executive in charge of restoring the Battery Maritime Building, point of departure for the ferry to Governors Island. Janine James, her design company, The Moderns, had done Jerry’s presentation book; they would also design our RFEI (request for expression of interest) submission. Paul Sladkus, head of Good News Broadcast; we worked out of his office space. Valentine Lehr, a consulting engineer whose firm had an international practice. Carman Moore, a composer with commissions from the New York Philharmonic, the San Francisco Symphony, the U.N., Lincoln Center (who also did a hip hop piece for his granddaughter to perform). There were more, many more.

We had meetings. Lots of them. The principals in a black-owned Wall Street investment firm, alas, I’ve forgotten the name. Insurance executives. Caleb Koeppel, a New York real estate billionaire (son of Alfred Koeppel). We had to go through two or three meetings with his advisory staff before meeting him.

It was a small room. Jerry and I on one side of the table. Caleb and, I believe, two or three associates on the other side of the table. One was Israeli. They listened to Jerry for over an hour, deep pin-drop silence. A world’s fair for a world’s that’s permanently fair. Dinner theater from around the world. Each member country has an office for trade representatives. A hotel where each room is furnished by a different designer; everything in the room is for sale. A world map 100s of yards in diameter. Orchids.

It was a good meeting. Nothing came of it.

Percy Fahrbach introduced us to the German CEO roundtable. Percy was the New York representative of Bertelsmann, the German media conglomerate. The German CEO roundtable was a forum for the 50 largest German firms having a presence in New York City.

We got 20 minutes with the head of the roundtable. I forget him name – it was over a decade ago – and I forget his company. I have vague recollections of the building, his office – sleek, modern, on an upper floor – and of the meeting itself. When our twenty minutes were up, Jerry had just barely gotten started on his ramble, but Mr. German CEO could have cared less. He was entranced. We left after an hour and a quarter.

It was a good meeting.

Time after time it went like that. Busy New York City executives gave Jerry an hour or two hours of their time so he could tell them about orchids for a permanent world’s fair in a world that’s permanently fair – this was long before Piketty and Occupy put inequality on the public agenda. These were sophisticated people. They could see that this wonderful idea made no ‘real-world’ sense at all. They could see that Jerry was doing this on a lick and a prayer.

Why’d they listen? Jerry’s charming. The idea’s enormously attractive. These men and women know what dire straits the world’s in. Jerry gave them hope. You can’t live without hope.

A mad dash down the West Side Highway

Our final proposal to GIPEC was due at noon on May 10, 2006. We ended up with, I don’t know, 200-300-400 pieces of paper, printed on both sides, in color, bound in four volumes, and nestled in an elegant black museum case. Twenty copies, thirty-copies, I forget.

It was a mad dash for three or four days. Tim Kunhardt of Z-Card North America gave us a room and a graphic designer; he’d been a long-term supporter of the project. I forget the name of the firm that actually put the books together and printed them. Spent hours in one of their rooms as well, punching out pages on my Mac laptop and sending them to, you know, the people who actually made physical stuff from those electronic bits.

Somehow we got everything printed and loaded into the van on the morning of May 10. We were in midtown Manhattan. GIPEC was accepting the proposals in the Battery Maritime Building at the southern tip of the island. It was only, I don’t know, two, three, four miles, not far. But this was Manhattan at midday. It was a quarter past eleven when the van pulled out into the street. We had forty-five minutes to deliver the proposals. If we were as much as a minute late, several years of work, down the tubes.

The driver was good, very good. It was like a mad dash in a Jackie Chan movie, but without Jackie fighting off villains at every street corner. There were no villains, just traffic and time. We made it with five minutes to spare.

Our work was done.

Of course our proposal wasn’t accepted. No proposals were accepted. I don’t think we were ever told why, but I’d bet that the financials killed the deal for everyone.

GIPEC scaled back its ambitions for the island. I believe there’s a school there. It’s now readily accessible to the public during the warm months. The non-descript buildings on the southern half of the island have been torn down and been replaced by a very cool park – at least it seems so from the pictures. I’ve not been there. I hear that last summer people were able to go glamping, as it’s called, on the island. “Glamping” = “glamour” + “camping”. A nice tent, 500-thread-count sheets, fine wine, gourmet food, $1000 a night. And superb views of the city.

* * * * *

Jerry did not quit. I continued to work with him, though my time commitment tapered off over the years. I haven’t seen him in well over a year or two, but we keep in touch by email and by phone – just chatted with him an hour or so ago.

Somewhere along the line he changed his name to Zeal. I don’t think he went through the legal process, though I could be wrong. But he answers to Zeal and that’s what he’s on his business cards.

He now has office space with Alan Ritchie, an architect. Ritchie was partners with Philip Johnson and took over the firm when Johnson died.

Alan Ritchie is a lucky man. He’s got hope in house.

As for my deferred compensation. Nothing was deferred. Hope is directed at the future, but its rewards are in the present.

Thank you Zeal.

The architectural renderings in this article are by Bob Kirchman of The Kirchman Studio. Here’s the executive summary of our GIPEC proposal, Governors Island as a World Resource Center.