Parul Sehgal in the New York Times:

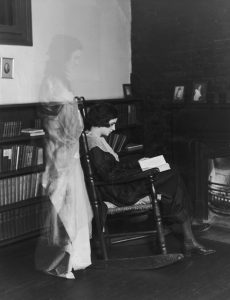

In 1960, the literary critic Leslie Fiedler delivered a eulogy for the ghost story in his classic study “Love and Death in the American Novel.” “An obsolescent subgenre,” he declared, with conspicuous relish; a “naïve” little form, as outmoded as its cheap effects, the table-tapping and flickering candlelight. Ghost stories belong to — brace yourself for maximum Fiedlerian venom — “middlebrow craftsmen,” who will peddle them to a rapidly dwindling audience and into an extinction that can’t come soon enough.

In 1960, the literary critic Leslie Fiedler delivered a eulogy for the ghost story in his classic study “Love and Death in the American Novel.” “An obsolescent subgenre,” he declared, with conspicuous relish; a “naïve” little form, as outmoded as its cheap effects, the table-tapping and flickering candlelight. Ghost stories belong to — brace yourself for maximum Fiedlerian venom — “middlebrow craftsmen,” who will peddle them to a rapidly dwindling audience and into an extinction that can’t come soon enough.

Not since Herman Melville’s publishers argued for less whale and more maidens in “Moby-Dick” (“young, perhaps voluptuous,” they dared to dream) has a literary judgment been so impressively off the mark.

Literature — the top-shelf, award-winning stuff — is positively ectoplasmic these days, crawling with hauntings, haints and wraiths of every stripe and disposition. These ghosts can be nosy and lubricious, as in George Saunders’s “Lincoln in the Bardo,” which followed a group of spectral busybodies in purgatory, observing the arrival of Abraham Lincoln’s newly deceased young son. They can be confused by their fates, as in Martin Riker’s new novel, “Samuel Johnson’s Eternal Return,” in which a man is unsettled to discover that his essence has migrated into the body of the man who killed him.

More here.