by Adele A Wilby

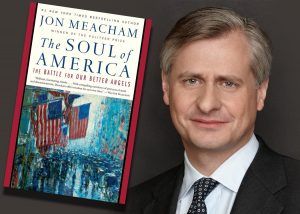

It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

Meacham is not concerned with examining the many sociological and economic factors that offer explanations as to why the American electorate put Trump in office, nor a critical examination of Trump’s suitability as president of the US. Instead, Meacham informs us Trump is not such an anomaly in terms of presidents of the US; ‘imperfection’, he reassures us, ‘is the rule not the exception’ insofar as US presidents are concerned. What differentiates Trump’s presidency from past imperfect presidents, in Meacham’s view, was their ability to dig deep into themselves and to rise above their personal views in the wider interests of the populace and the nation when required to do so, whereas Trump rarely has.

The history of the US, Meacham’s exposition reveals, is replete with presidents with nefarious political views and social practices that besmirch the US image of its own ‘exceptionalism’. Arguably, US ‘exceptionalism’ lies in the fact its founding fathers and past presidents, at crucial times in the nation’s history, challenged their own political views and veered on the side of social progress. Meacham reveals to us just how far US politics has historically epitomised a struggle between what he refers to as the ‘better angels’ and the ‘darker forces’ within past US presidents for it to emerge as the country it is today, until the election of Trump that is. However, Meacham reassures us that the ‘darker’ side of politics that Trump’s presidency represents for so many, will pass, and with the end of his time in office, the opportunity for the people to elect a president of a different calibre will occur again. How then does Meacham explain the assumption to office of Trump?

To develop his argument, Meacham delves into the history of the political thinking and personal reflections of US presidents, and establishes how and what he considers to be the ‘American soul’. The use of the term ‘soul’ initially exposes Meacham’s argument to contestation, particularly since he only briefly explores the philosophical usage of what is a controversial subject. Then again, it is not the purpose of his book to engage in a philosophical treatise on what could be or whether in fact there is such a thing as the ‘soul’. Instead he accepts the premise, and he turns to Saint Augustine of Hippo’s writing in The City of Godfor his definition of ‘soul’ as ‘an assemblage of reasonable beings bound together by a common agreement as to the object of their love’. Perhaps Meacham’s view of ‘soul’ as being ‘what makes us us, whether we are speaking of a person or of a people’ is easier to relate to than the vague notion of an object of love as constitutive of a nation’s ‘soul’.

Nevertheless, Meacham’s usage of the concept of ‘soul’ inevitably leads on to the question of what have Americans ‘loved’ in common throughout their history that amounts to an ‘American soul’? What is the American soul? Meacham’s answer to that fundamental question is, ‘a belief in the proposition, as Jefferson put it in the Declaration, that all men are created equal’.

While a belief in the view that all people are created equal is not so extra-ordinary in the twenty first century, and indeed flows naturally to so many people, the principle of equality has had to be enshrined within the US constitution for it to hold sway over time. Yet, despite its embeddedness in constitutional legality there are those in the US who are prepared to contest such a political ideal.

When the concept of ‘equality’ between people within the US is positioned in the wider context of just how the US was founded: the genocide of the original inhabitants of the land, slavery, the perpetuation of white ‘supremacy’ through Jim Crow, and an ongoing legacy of racism and sexism, the emergence of the humanist ideal of ‘equality’ between people as the ‘soul’ of the American nation is remarkable. None of these oppressive and exploitative practices could ever have come into being without the support of an ideology to give legitimacy to such inhumanity; it had to be explained and justified, and accepted by the vast sections of people, and it is only ideology that can complete such a task, an ideology that rejects the idea that we are all created equal in our humanity, that some peoples are superior to others, particularly those with white skin, and that was the work of the ideologies of racism and white supremacy. But such ideologies have not detached themselves from US history and remain deeply rooted and firmly embedded, and persist amongst sections of the US populace to one degree or another, and in one form or another till this day; the ‘darker forces’ in Meacham’s terms.

Meacham does not shy away from addressing the ‘darker’ side of American history, in fact it is fundamental to his argument in accounting for Trump’s presidency. For him, the ‘American soul’ is engaged in an ‘eternal struggle’ to overcome the ‘darker forces’ deep in its heart. Indeed, it was in response to the abominable practices upon which the US is built that gave rise to the impetus for past US presidents to acknowledge the inhumanity of institutionalised slavery, racism and sexism, and to articulate ideals of ‘equality’; the ‘better angels’ in the ‘American soul’. However, as former present Ronald Reagan, although speaking in a different historical context, commented, ‘history is a living thing that never dies’. Indeed, and so it within the US; the ‘eternal struggle’ between the ‘better angels’ who promoted the ideal of the equality of peoples, and the ‘darker forces’ who uphold and promote racism, discrimination and white supremacist views, are in battle for control over the ‘American soul’, and the battle rages in contemporary times.

The political views of a spectrum of past presidents from the time of George Washington till Ronald Reagan explored by Meacham reveals just how far US presidents have practised racism and held white supremacist views. George Washington for example, was a slave owner. Truman, according to Meacham, made racist slurs in private. Theodore Roosevelt, a reformist, was at the same time a harbinger of white supremacist views in his belief that the destiny of the Anglo-Saxon peoples was to rule the world. However, what puts these presidents on the side of the ‘better angels’ in US political history, in Meacham’s view, was their ability to rise above their own proclivity for the forces of darkness within their thinking. Past presidents drew on their own humanity and the guiding principles of the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights as guiding principles to assist them in their decision making to further the greater good, and the nation’s interests. Ultimately, the presidents who have opted for the side of the ‘better angels’ have contributed to the emergence of the US as the leader of the ‘free’ world, and upholder of liberal ideals of democracy, equality, individual freedoms, and free speech, at least in principle for the American people.

Thus, in Meacham’s analysis many of the past presidents in US history, as repositories of the countervailing forces, have assumed major roles in determining the direction of the nation. ‘A president,’ Meacham tells us, ‘sets a tone for the nation and helps tailor habits of heart and of mind’, and furthermore, ‘we are more likely to choose the right path when we are encouraged to do so from the very top’. There is little to dispute on that point.

Past presidents too, would agree with Meacham. Not known as a progressive before entering the White House, but with an acute sense of the political, Lyndon Johnson knew that handled properly, the passage of civil rights legislation in the US would be a historical moment. When advised to ease off on his commitment to civil rights legislation following the assassination of president Kennedy in 1964, Johnson revealed not only his leadership qualities, but his determination to do what he thought was right for the country and to address the discrimination against African Americans. Defying the opposition from his colleagues, the concerns of his southern constituency, and risking the possibility of losing the presidential election, a determined Johnson quipped in reply, ‘well what is the presidency supposed to do?’

Meacham’s assertion that ‘our greatest leaders have pointed towards the future – not at this group or that sect’ has credibility. However, as Meacham points out, ‘a tragic element of history is that every advance must contend with forces of reaction’ (page 258). Indeed, and what is certain is that the ‘better angels’ have been unable to totally vanquish the dark forces from the American polity; the forces of racism, discrimination, and the ideology of white supremacy; they lurk, waiting for an opportune moment to seize the upper hand in the battle for the ‘American soul’. Trump’s candidacy and subsequent assumption to office, as we have learned, has provided the opportunity to breathe new life into those dark elements embedded in the heart of US politics.

Trump’s racial profiling and divisive comments on issues of immigration, his misogynist statements, his nationalist rhetoric, and his nativism, amongst other things, place Trump within the realms of the ‘darker forces’, in terms of US presidents. He has failed to demonstrate his ability to rise above those forces as exemplified most explicitly in his reluctance to outrightly condemn Nazis and neo-Nazis in a violent confrontation with Americans who stood against such views in Charlottesville in 2017. As Obama recently commented in a speech in Illinois, ’how hard can that be saying Nazis are bad?’ We can only assume that Trump is unable to find fascist political views abhorrent. He is, as Meacham says when discussing the tradition of populists such as Strom Thurmond and George Wallace in US political history, the heir to such traditions.

But it is not only the political views of the president that are important, but the character of the individual in the office too. Woodrow Wilson realised the significance of character in the person of the presidency when, speaking of the president’s approach, he says:

He is the president of no constituency, but of the whole people. When he speaks in his true character, he speaks for no special interest. If he rightly interprets the national thought and boldly insists upon it, he is irresistible; and the country never feels the zest of action so much as when its president is of such insight and calibre.

Eisenhower too, when speaking on leadership comments:

Now look, I happen to know a little about leadership. I’ve had to work with a lot of nations, for that matter, at odds with each other. And I tell you this: you do not lead by hitting people over the head. Any damn fool can do that, but it’s usually called ‘assault’ – not ‘leadership’… I’ll tell you what leadership is. It’s persuasion – and conciliation – and education – and patience. It’s long, slow, tough work. That’s the only kind of leadership I know – or believe in – or will practice.

Trump, as we can see, has a great deal to learn about ‘high’ politics from the experience of his predecessors.

Meacham has effectively revealed the way in which past presidents have sided with the ‘better angels’ in the battle against the ‘darker forces’ of US politics, and in so doing cultivated what he refers to as the ‘American soul’. However, his exposure of the origins of darker thinking in US political life reminds us that ‘progressive’ aspects for which the US is known can never be taken for granted, and just how alive is the enduring legacy of the ‘darker forces’ in US history. But even though the American people are not the focus of Meacham’s analysis, the final sections of his conclusion can be seen as an appeal to the people for vigilance and action if the ‘darker forces’ are to be contained. Here too he draws on the thinking of past presidents. Engage in politics, resist tribalism, remember history, respect facts and deploy reason, is the advice as he arms the people with strategies to challenge and defeat the demagogic rhetoric manifest most poignantly in the incumbent president. It remains to be seen therefore, on which side of the struggle for the ‘American soul’ the people will side: the ‘better angels’, to assist with the bending of ‘the arc of the moral universe…’, or the ‘darker forces’ in the ‘American soul’. As Eleanor Roosevelt says, ‘it is not so much the powerful leaders that determine our destiny as the much more powerful influence of the combined voice of the people themselves’.