Petal Samuel in Public Books:

Many black scholars—especially those who study black life, history, and culture—would recognize an uncomfortable and familiar situation that epitomizes the trials of coming through the academy: the moment when a colleague, professor, or student questions whether or not our work truly accords with the standards and conventions of our discipline, of the academy itself. We are subtly and overtly asked if our analyses are truly objective, if our methodologies are sound, and if our subject matter is accessible with wide enough appeal. We know that words like “rigor,” “breadth,” “accessibility,” and “objectivity” in traditional academic disciplines often encode institutional racism, and that the very methodologies and analytical practices we’re urged to master were never meant to accommodate the study of black life. Yet, to depart from academic orthodoxies can have real consequences: isolation, lack of support, getting passed over for opportunities and honors, poor evaluations, promotion denials, and, in some cases, exile from academia.

Many black scholars—especially those who study black life, history, and culture—would recognize an uncomfortable and familiar situation that epitomizes the trials of coming through the academy: the moment when a colleague, professor, or student questions whether or not our work truly accords with the standards and conventions of our discipline, of the academy itself. We are subtly and overtly asked if our analyses are truly objective, if our methodologies are sound, and if our subject matter is accessible with wide enough appeal. We know that words like “rigor,” “breadth,” “accessibility,” and “objectivity” in traditional academic disciplines often encode institutional racism, and that the very methodologies and analytical practices we’re urged to master were never meant to accommodate the study of black life. Yet, to depart from academic orthodoxies can have real consequences: isolation, lack of support, getting passed over for opportunities and honors, poor evaluations, promotion denials, and, in some cases, exile from academia.

Even as universities systemically generate hostile environments for black people, leaving academia—a necessary act of self-preservation for many—is additionally freighted with false notions of intellectual and personal failure. Keguro Macharia in “On Quitting” writes about an inability to imagine or desire the life of privilege, access, and security promised by academic institutions. “I’m not sure this is ‘the life’ I want to imagine. I worry about any life that can so readily be ‘imagined.’ Where is the space for fantasy, for play, for the unexpected, for the surprising?” Macharia pointedly notes, “We can complain—that’s part of our affective duty. But to leave is unthinkable. It is unthinkable in a place that teaches thinking.”

More here.

I remember the moment when code began to interest me. It was the tail end of 2013 and a cult was forming around a mysterious “crypto-currency” called bitcoin in the excitable tech quarters of London, New York and San Francisco. None of the editors I spoke to had heard of it – very few people had back then – but eventually one of them commissioned me to write the first British magazine piece on the subject. The story is now well known. The system’s pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, had appeared out of nowhere, dropped his ingenious system of near-anonymous, decentralised money into the world, then vanished, leaving only a handful of writings and 100,000 lines of code as clues to his identity. Not much to go on. Yet while reporting the piece, I was astonished to find other programmers approaching Satoshi’s code like literary critics, drawing conclusions about his likely age, background, personality and motivation from his style and approach. Even his choice of programming language – C++ – generated intrigue. Though difficult to use, it is lean, fast and predictable. Programmers choose languages the way civilians choose where to live and some experts suspected Satoshi of not being “native” to C++. By the end of my investigation I felt that I knew this shadowy character and tingled with curiosity about the coder’s art. For the very first time I began to suspect that coding really was an art, and would reward examination.

I remember the moment when code began to interest me. It was the tail end of 2013 and a cult was forming around a mysterious “crypto-currency” called bitcoin in the excitable tech quarters of London, New York and San Francisco. None of the editors I spoke to had heard of it – very few people had back then – but eventually one of them commissioned me to write the first British magazine piece on the subject. The story is now well known. The system’s pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, had appeared out of nowhere, dropped his ingenious system of near-anonymous, decentralised money into the world, then vanished, leaving only a handful of writings and 100,000 lines of code as clues to his identity. Not much to go on. Yet while reporting the piece, I was astonished to find other programmers approaching Satoshi’s code like literary critics, drawing conclusions about his likely age, background, personality and motivation from his style and approach. Even his choice of programming language – C++ – generated intrigue. Though difficult to use, it is lean, fast and predictable. Programmers choose languages the way civilians choose where to live and some experts suspected Satoshi of not being “native” to C++. By the end of my investigation I felt that I knew this shadowy character and tingled with curiosity about the coder’s art. For the very first time I began to suspect that coding really was an art, and would reward examination. What would convince you that aliens existed? The question came up recently at a conference on astrobiology, held at Stanford University in California. Several ideas were tossed around – unusual gases in a planet’s atmosphere, strange heat gradients on its surface. But none felt persuasive. Finally, one scientist offered the solution: a photograph. There was some laughter and a murmur of approval from the audience of researchers: yes, a photo of an alien would be convincing evidence, the holy grail of proof that we’re not alone.

What would convince you that aliens existed? The question came up recently at a conference on astrobiology, held at Stanford University in California. Several ideas were tossed around – unusual gases in a planet’s atmosphere, strange heat gradients on its surface. But none felt persuasive. Finally, one scientist offered the solution: a photograph. There was some laughter and a murmur of approval from the audience of researchers: yes, a photo of an alien would be convincing evidence, the holy grail of proof that we’re not alone. Electrons are still almost perfectly round, a new measurement shows. A more squished shape could hint at the presence of never-before-seen subatomic particles, so the result stymies the search for new physics.

Electrons are still almost perfectly round, a new measurement shows. A more squished shape could hint at the presence of never-before-seen subatomic particles, so the result stymies the search for new physics. Climate change necessarily presents a profound political challenge in the present historical era, for the simple reason that we are courting ecological disaster by not advancing a viable global climate-stabilization project.

Climate change necessarily presents a profound political challenge in the present historical era, for the simple reason that we are courting ecological disaster by not advancing a viable global climate-stabilization project.

Two bodies of work, both particularly symptomatic of the bankruptcy of egalitarianism and the triumph of individualism against a background of Western resignation, have been hugely successful both in France and elsewhere (a sign that they resonate deeply in an era of globalization and crisis). Virginie Despentes and Michel Houellebecq, each in their idiosyncratic way, do not just describe these social changes and their effects, but have also set about identifying their horizons, or the possibilities of survival beyond them. They take the way the naturalist novel depicts society and adapt it to suit their purposes, adding imagery and narrative techniques borrowed from a strand of English-language literature hitherto referred to condescendingly as ‘popular’. But it is precisely these influences, the product of a counterculture born out of globalization and the twentieth century, that enable them to bear the weight of the singularities of our contemporary modernity: science fiction in in Houellebecq’s Atomised (1998), futuristic dystopian narrative in his Submission (2015), or crime noir in Despentes’s Vernon Subutex (2015–2017).

Two bodies of work, both particularly symptomatic of the bankruptcy of egalitarianism and the triumph of individualism against a background of Western resignation, have been hugely successful both in France and elsewhere (a sign that they resonate deeply in an era of globalization and crisis). Virginie Despentes and Michel Houellebecq, each in their idiosyncratic way, do not just describe these social changes and their effects, but have also set about identifying their horizons, or the possibilities of survival beyond them. They take the way the naturalist novel depicts society and adapt it to suit their purposes, adding imagery and narrative techniques borrowed from a strand of English-language literature hitherto referred to condescendingly as ‘popular’. But it is precisely these influences, the product of a counterculture born out of globalization and the twentieth century, that enable them to bear the weight of the singularities of our contemporary modernity: science fiction in in Houellebecq’s Atomised (1998), futuristic dystopian narrative in his Submission (2015), or crime noir in Despentes’s Vernon Subutex (2015–2017). “Voices from the Moon” is my favorite of all Andre Dubus’s stories and novellas. It concerns itself unabashedly and unsentimentally with love—the love of parents for their children, of men for women and women for women, of a boy’s love for God, and a teenage girl’s love for cigarettes. The story is too rich to paraphrase, but in brief, a divorced man has fallen in love with his son’s ex-wife, and she with him. They mean to live together. The family is shaken to its roots by the apparent betrayals involved, and not least by the social impropriety of such an arrangement—its radical flouting of convention. Yet as the story proceeds we see its people react not with the sort of virtuous outrage we might expect, but with hard-won understanding, generosity, forgiveness, and love. In essence, the family members declare their independence from submissive concern or embarrassment about how things might look to others, finding freedom in their refusal to let their lives be shaped by the expectations and decorums of social custom. Sensational as the premise of the story may be—it was inspired by a newspaper article Dubus happened upon—he illuminates his people’s lives not by heating up the drama inherent in their situation, but by allowing each of them quiet, ordinary moments in which to reveal themselves, to profound, extraordinary effect. It is altogether Dubus’s strangest, most moving and beautiful piece of work.

“Voices from the Moon” is my favorite of all Andre Dubus’s stories and novellas. It concerns itself unabashedly and unsentimentally with love—the love of parents for their children, of men for women and women for women, of a boy’s love for God, and a teenage girl’s love for cigarettes. The story is too rich to paraphrase, but in brief, a divorced man has fallen in love with his son’s ex-wife, and she with him. They mean to live together. The family is shaken to its roots by the apparent betrayals involved, and not least by the social impropriety of such an arrangement—its radical flouting of convention. Yet as the story proceeds we see its people react not with the sort of virtuous outrage we might expect, but with hard-won understanding, generosity, forgiveness, and love. In essence, the family members declare their independence from submissive concern or embarrassment about how things might look to others, finding freedom in their refusal to let their lives be shaped by the expectations and decorums of social custom. Sensational as the premise of the story may be—it was inspired by a newspaper article Dubus happened upon—he illuminates his people’s lives not by heating up the drama inherent in their situation, but by allowing each of them quiet, ordinary moments in which to reveal themselves, to profound, extraordinary effect. It is altogether Dubus’s strangest, most moving and beautiful piece of work. Reading medieval literature, it’s hard not to be impressed with how much the characters get done—as when we read about King Harold doing battle in one of the Sagas of the Icelanders, written in about 1230. The first sentence bristles with purposeful action: “King Harold proclaimed a general levy, and gathered a fleet, summoning his forces far and wide through the land.” By the end of the third paragraph, the king has launched his fleet against a rebel army, fought numerous battles involving “much slaughter in either host,” bound up the wounds of his men, dispensed rewards to the loyal, and “was supreme over all Norway.” What the saga doesn’t tell us is how Harold felt about any of this, whether his drive to conquer was fueled by a tyrannical father’s barely concealed contempt, or whether his legacy ultimately surpassed or fell short of his deepest hopes.

Reading medieval literature, it’s hard not to be impressed with how much the characters get done—as when we read about King Harold doing battle in one of the Sagas of the Icelanders, written in about 1230. The first sentence bristles with purposeful action: “King Harold proclaimed a general levy, and gathered a fleet, summoning his forces far and wide through the land.” By the end of the third paragraph, the king has launched his fleet against a rebel army, fought numerous battles involving “much slaughter in either host,” bound up the wounds of his men, dispensed rewards to the loyal, and “was supreme over all Norway.” What the saga doesn’t tell us is how Harold felt about any of this, whether his drive to conquer was fueled by a tyrannical father’s barely concealed contempt, or whether his legacy ultimately surpassed or fell short of his deepest hopes. They put GPS chips in pets and migratory birds now. How can someone flying around in a 65-million-dollar machine get lost?” With these words – spoken by a US airman who has just crashed his jet in an unnamed desert –

They put GPS chips in pets and migratory birds now. How can someone flying around in a 65-million-dollar machine get lost?” With these words – spoken by a US airman who has just crashed his jet in an unnamed desert –  In the five years since I moved to Paris as an American philosopher working within the French system, my disdain for what Americans know as ‘French theory’, and particularly for the American reception of it, has only deepened. Sometimes I find it burdensome to be pursuing my work so close to the belly of this noisome beast (my campus of the University of Paris lies on the city’s southeastern border, while the belly, properly anatomically speaking, is two RER stops to the west (its external gonads are up in St. Denis)), but for the most part I am happy to process this unanticipated twist in my career as one of my life’s animating ironies, and to milk this irony for insights that I would not be able to come by if I were either geographically far away from this intellectual culture, or a fawning convert to it.

In the five years since I moved to Paris as an American philosopher working within the French system, my disdain for what Americans know as ‘French theory’, and particularly for the American reception of it, has only deepened. Sometimes I find it burdensome to be pursuing my work so close to the belly of this noisome beast (my campus of the University of Paris lies on the city’s southeastern border, while the belly, properly anatomically speaking, is two RER stops to the west (its external gonads are up in St. Denis)), but for the most part I am happy to process this unanticipated twist in my career as one of my life’s animating ironies, and to milk this irony for insights that I would not be able to come by if I were either geographically far away from this intellectual culture, or a fawning convert to it. An abundance of social science research indicates that high economic inequality comes along with several undesirable outcomes, such as higher levels of violence and lower levels of health, happiness and satisfaction with life. But inequality has been rising in almost all developed countries since the 1970s, which raises an important question. If high inequality is detrimental to the well-being of a large majority of the populace and if democracy is about realizing “the will of the people,” why has inequality been allowed to increase in most democracies? Put differently, if most people would benefit from enhancing equality, why have voters not elected politicians who would implement policies to do that? This is one of the most significant paradoxes of our time.

An abundance of social science research indicates that high economic inequality comes along with several undesirable outcomes, such as higher levels of violence and lower levels of health, happiness and satisfaction with life. But inequality has been rising in almost all developed countries since the 1970s, which raises an important question. If high inequality is detrimental to the well-being of a large majority of the populace and if democracy is about realizing “the will of the people,” why has inequality been allowed to increase in most democracies? Put differently, if most people would benefit from enhancing equality, why have voters not elected politicians who would implement policies to do that? This is one of the most significant paradoxes of our time. “Marnie,” my new opera, which has

“Marnie,” my new opera, which has  Early in

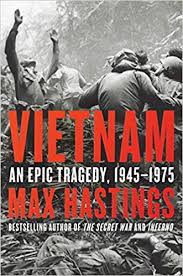

Early in  According to Max Hastings, it was ‘an epic tragedy’ for those who lived through it. From start to finish, the wars for Vietnam sowed death and destruction across the land. Starting with the outbreak of the French war with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh in 1945 and ending with the inglorious American evacuation from Saigon in 1975, Hastings focuses on how combatants and civilians experienced war. He draws upon an impressive range of sources to take the reader into the line of fire. Through vivid descriptions and moving prose, he shows us the suffering, trauma and death that the French and especially American campaigns inflicted upon the civilians and soldiers on all sides who found themselves caught up in what turned into a conflagration of mind-boggling violence.

According to Max Hastings, it was ‘an epic tragedy’ for those who lived through it. From start to finish, the wars for Vietnam sowed death and destruction across the land. Starting with the outbreak of the French war with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh in 1945 and ending with the inglorious American evacuation from Saigon in 1975, Hastings focuses on how combatants and civilians experienced war. He draws upon an impressive range of sources to take the reader into the line of fire. Through vivid descriptions and moving prose, he shows us the suffering, trauma and death that the French and especially American campaigns inflicted upon the civilians and soldiers on all sides who found themselves caught up in what turned into a conflagration of mind-boggling violence. Berlin’s absorption in the history of ideas dates back almost to the beginning of his academic career. In 1933 he was commissioned to write a book on Karl Marx, which was published in 1939 and is still in print today. His reading of Marx and Marx’s predecessors, especially the philosophers of the Enlightenment, and even more their opponents, the “Counter-Enlightenment” as he called them, fuelled his thought for the rest of his life.

Berlin’s absorption in the history of ideas dates back almost to the beginning of his academic career. In 1933 he was commissioned to write a book on Karl Marx, which was published in 1939 and is still in print today. His reading of Marx and Marx’s predecessors, especially the philosophers of the Enlightenment, and even more their opponents, the “Counter-Enlightenment” as he called them, fuelled his thought for the rest of his life.