Clifton Mark in Aeon:

In 1717, Voltaire was arrested, some might say, for giving offence. He had published a ‘satirical’ verse that opens by calling the Duc d’Orleans, the then Regent of France, ‘an inhuman tyrant, famous for poison, atheism, and incest’. This pungent personal attack became so popular it was sung on the streets of Paris. In response, the Duc had Voltaire arrested without accusation or trial. The author spent 11 months in the Bastille.

In 1717, Voltaire was arrested, some might say, for giving offence. He had published a ‘satirical’ verse that opens by calling the Duc d’Orleans, the then Regent of France, ‘an inhuman tyrant, famous for poison, atheism, and incest’. This pungent personal attack became so popular it was sung on the streets of Paris. In response, the Duc had Voltaire arrested without accusation or trial. The author spent 11 months in the Bastille.

Such stories help to explain why Voltaire turns up so frequently in today’s debates over offensive speech, which are driven by the sense that members of historically marginalised groups have become increasingly willing to take offence to speech that they feel implies their exclusion or inferiority. Many believe that this trend has gone too far. In 2016, the Pew Research Centre in the US found that a majority of Americans believe that ‘too many people are easily offended these days over language’. Angus Reid, a Canadian polling company, found similar results – in their poll, 80 per cent of Canadians agreed with the statement: ‘These days, it seems like you can’t say anything without someone feeling offended.’ This sense is not without basis. Public discourse is filled with confrontations over offensive speech. Hardly a day goes by when some public figure is not called out for offensive behaviour, or when another argues that all this offence-taking is a threat to free speech.

More here.

Economics, like other sciences (social and otherwise), is about what the world does; but it’s natural for economists to occasionally wander out into the question of what we should do as we live in the world. A very good example of this is a new book by economist Tyler Cowen,

Economics, like other sciences (social and otherwise), is about what the world does; but it’s natural for economists to occasionally wander out into the question of what we should do as we live in the world. A very good example of this is a new book by economist Tyler Cowen,  Was Sharmila Sen “happy” on the first morning she woke up in the United States to the strange smell of bacon frying? That’s what her young son wants to know when, near the end of Not Quite Not White—Sen’s powerful memoir and meditation on race and migration—he interviews her for a school project on immigration. It turns out we already know the answer. “It was a complex animal smell,” we read earlier of the odor she ever after associates with her 1982 arrival in Boston from Calcutta, “making my mouth water and my stomach churn in revulsion at the same time.”

Was Sharmila Sen “happy” on the first morning she woke up in the United States to the strange smell of bacon frying? That’s what her young son wants to know when, near the end of Not Quite Not White—Sen’s powerful memoir and meditation on race and migration—he interviews her for a school project on immigration. It turns out we already know the answer. “It was a complex animal smell,” we read earlier of the odor she ever after associates with her 1982 arrival in Boston from Calcutta, “making my mouth water and my stomach churn in revulsion at the same time.” Princess Mononoke inaugurated a new chapter in Miyazakiworld. Ambitious and angry, it expressed the director’s increasingly complex worldview, putting on film the tight intermixture of frustration, brutality, animistic spirituality, and cautious hope that he had honed in his manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The film offers a mythic scope, unprecedented depictions of violence and environmental collapse, and a powerful vision of the sublime, all within the director’s first-ever attempt at a jidaigeki, or historical film. It also moves further away from the family fare that had made him a treasured household name in Japan.

Princess Mononoke inaugurated a new chapter in Miyazakiworld. Ambitious and angry, it expressed the director’s increasingly complex worldview, putting on film the tight intermixture of frustration, brutality, animistic spirituality, and cautious hope that he had honed in his manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The film offers a mythic scope, unprecedented depictions of violence and environmental collapse, and a powerful vision of the sublime, all within the director’s first-ever attempt at a jidaigeki, or historical film. It also moves further away from the family fare that had made him a treasured household name in Japan. The publication of Cynthia Haven’s full-dress biography of René Girard, a major figure in the “French invasion” that stormed the beaches of American academe across the final decades of the last millennium, marks a notable event on many fronts: academic, professional, literary, philosophical; and for some individuals among generations of students world-wide, deeply personal. In my case, that means religious.

The publication of Cynthia Haven’s full-dress biography of René Girard, a major figure in the “French invasion” that stormed the beaches of American academe across the final decades of the last millennium, marks a notable event on many fronts: academic, professional, literary, philosophical; and for some individuals among generations of students world-wide, deeply personal. In my case, that means religious. It is unpleasant to feel alone. Loneliness can be a source of desolation and anguish. That is why it is understandable that many of us look for ways to fix it. Some seek out therapy, others join social clubs and attempt to forge new relationships and contacts. The refusal to accept social isolation and the search for solidarity shapes who we are and influences community life. Loneliness is not just a condition that we must suffer. It also provides people with an opportunity to gain an understanding of themselves and of their world. The theologian Paul Tillich exhorted people to embrace their loneliness, because it forces us to engage with life’s two most fundamental questions: what is the meaning of life and how should we understand ourselves?

It is unpleasant to feel alone. Loneliness can be a source of desolation and anguish. That is why it is understandable that many of us look for ways to fix it. Some seek out therapy, others join social clubs and attempt to forge new relationships and contacts. The refusal to accept social isolation and the search for solidarity shapes who we are and influences community life. Loneliness is not just a condition that we must suffer. It also provides people with an opportunity to gain an understanding of themselves and of their world. The theologian Paul Tillich exhorted people to embrace their loneliness, because it forces us to engage with life’s two most fundamental questions: what is the meaning of life and how should we understand ourselves? Édouard Vuillard was 60 when his mother died in 1928. He had never lived with anybody else. “My mother is my muse,” he confessed to a friend, and the truth of that is apparent in more than 500 images of this small, stout widow with her tight bun and patterned dresses running a sewing business in the various Paris apartments they shared. She is there from first to last.

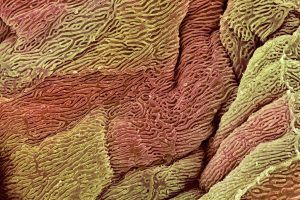

Édouard Vuillard was 60 when his mother died in 1928. He had never lived with anybody else. “My mother is my muse,” he confessed to a friend, and the truth of that is apparent in more than 500 images of this small, stout widow with her tight bun and patterned dresses running a sewing business in the various Paris apartments they shared. She is there from first to last. Cancer is a disease of mutations. Tumor cells are riddled with genetic mutations not found in healthy cells. Scientists estimate that it takes five to 10 key mutations for a healthy cell to become cancerous. Some of these mutations can be caused by assaults from the environment, such as ultraviolet rays and cigarette smoke. Others arise from harmful molecules produced by the cells themselves. In recent years, researchers have begun taking a closer look at these mutations, to try to understand how they arise in healthy cells, and what causes these cells to later erupt into full-blown cancer. The research has produced some major surprises. For instance, it turns out that a large portion of the cells in healthy people carry far more mutations than expected, including some mutations thought to be the prime drivers of cancer. These mutations make a cell grow faster than others, raising the question of why full-blown cancer isn’t far more common. “This is quite a fundamental piece of biology that we were unaware of,” said Inigo Martincorena, a geneticist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England.These lurking mutations went unnoticed for so long because the tools for examining DNA were too crude. If scientists wanted to sequence the entire genome of tumor cells, they had to gather millions of cells and analyze all of the DNA. A mutation, to be detectable, had to be very common.

Cancer is a disease of mutations. Tumor cells are riddled with genetic mutations not found in healthy cells. Scientists estimate that it takes five to 10 key mutations for a healthy cell to become cancerous. Some of these mutations can be caused by assaults from the environment, such as ultraviolet rays and cigarette smoke. Others arise from harmful molecules produced by the cells themselves. In recent years, researchers have begun taking a closer look at these mutations, to try to understand how they arise in healthy cells, and what causes these cells to later erupt into full-blown cancer. The research has produced some major surprises. For instance, it turns out that a large portion of the cells in healthy people carry far more mutations than expected, including some mutations thought to be the prime drivers of cancer. These mutations make a cell grow faster than others, raising the question of why full-blown cancer isn’t far more common. “This is quite a fundamental piece of biology that we were unaware of,” said Inigo Martincorena, a geneticist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England.These lurking mutations went unnoticed for so long because the tools for examining DNA were too crude. If scientists wanted to sequence the entire genome of tumor cells, they had to gather millions of cells and analyze all of the DNA. A mutation, to be detectable, had to be very common.

A bit of self indulgence – also a kind of preface to all the 3 Quarks Daily

A bit of self indulgence – also a kind of preface to all the 3 Quarks Daily

1. Bored, and with little to occupy their time, two cousins, Elsie, who was 16, and Frances, who was 10, decided to play around with photography. At a river near where they lived, they manipulated an image so that it looked as if they were interacting with little, magical winged creatures — fairies.

1. Bored, and with little to occupy their time, two cousins, Elsie, who was 16, and Frances, who was 10, decided to play around with photography. At a river near where they lived, they manipulated an image so that it looked as if they were interacting with little, magical winged creatures — fairies.

Two weeks ago, Maniza Naqvi evocatively wrote here on the resonance of a mythological rape in the eventual confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court (

Two weeks ago, Maniza Naqvi evocatively wrote here on the resonance of a mythological rape in the eventual confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court ( Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.

Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.