Kenneth Miller in Discover:

Month: October 2018

Can a Cat Have an Existential Crisis?

Britt Peterson in Nautilus:

When I first adopted Lucas nine years ago from a cat rescue organization in Washington, D.C., his name was Puck. “Because he’s mischievous,” his foster mother said. Although we changed the name, her analysis proved correct. Unlike his brother Tip, whom I also adopted, a gray cat with white paws and an Eeyore-ish dour doofy sweetness, Lucas was from the start a fierce black fireball, a menace to stray toes or blanket fringes or loose items on tabletops. He was my alarm clock in the morning with his habit of knocking my hairbrush, deodorant, and earrings box off my bureau until I got up to feed him.

When I first adopted Lucas nine years ago from a cat rescue organization in Washington, D.C., his name was Puck. “Because he’s mischievous,” his foster mother said. Although we changed the name, her analysis proved correct. Unlike his brother Tip, whom I also adopted, a gray cat with white paws and an Eeyore-ish dour doofy sweetness, Lucas was from the start a fierce black fireball, a menace to stray toes or blanket fringes or loose items on tabletops. He was my alarm clock in the morning with his habit of knocking my hairbrush, deodorant, and earrings box off my bureau until I got up to feed him.

Then, almost four years ago, my husband and I had a child. Lucas, no longer the most important small creature in the apartment, retreated to the top shelf of his cat tree, where he would lie all day, staring morosely over the edge. When he did want attention, his solicitations became aggressive. Instead of waiting until 7 a.m. to start knocking things off of the bureau, he started hopping up there at 4 a.m. We closed the bedroom door and were still woken up at 4 every day by Lucas rattling the doorknob or hurling the weight of his 13-pound body against it. At mealtimes he would gobble down his food and then shove Tip out of the way to eat Tip’s food. He started marking the carpets in our living room and my son’s room, and his play with Tip turned more violent too.

I made an appointment, first, with a pet behavior specialist and, five months later, when her initially helpful suggestions didn’t change Lucas’s behavior, with a vet. The vet described Lucas’s condition as “anxiety” and prescribed fluoxetine, a generic for Prozac that’s often prescribed for animals. While I had felt a mixture of frustration and pity toward Lucas, in that moment I experienced a surprising stir of recognition. Over a decade ago, during six months in college, I had panic attacks every other day. I was given a similar diagnosis—panic disorder being a major anxiety disorder—and was prescribed a similar medication.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Americanathon

Waiting for the new ice age to come along

Like a dawdling child from a previous eon,

Waiting for the homeless man to go on home

With his tired cardboard sign that says “anything helps,”

Waiting for a cure, waiting for the closeout sale,

The black sail, a new tarboosh and a tiny red car,

A new improved and safer war,

A harmless war, a war that we could win,

A brain tumor in your smart phone, an entitlement check

(Will you please check on my entitlement?),

Waiting for the bank hack, the backtrack, the take,

Waiting for a calabash, the calaboose, an acquisition,

An accusation, resuscitation from a total stranger,

Waiting for the finish line to explode.

from: Everything We Always Knew Was True

Copper Canyon Press, 2016

To reduce inequality, abolish Ivy League

Glenn Harlan Reynolds in USA Today:

As former Labor secretary Robert Reich recently noted, Ivy League schools are government-subsidized playgrounds for the rich: “Imagine a system of college education supported by high and growing government spending on elite private universities that mainly educate children of the wealthy and upper-middle class, and low and declining government spending on public universities that educate large numbers of children from the working class and the poor.

As former Labor secretary Robert Reich recently noted, Ivy League schools are government-subsidized playgrounds for the rich: “Imagine a system of college education supported by high and growing government spending on elite private universities that mainly educate children of the wealthy and upper-middle class, and low and declining government spending on public universities that educate large numbers of children from the working class and the poor.

“You can stop imagining,” Reich wrote. “That’s the American system right now. … Private university endowments are now around $550 billion, centered in a handful of prestigious institutions. Harvard’s endowment is over $32 billion, followed by Yale at $20.8 billion, Stanford at $18.6 billion, and Princeton at $18.2 billion. Each of these endowments increased last year by more than $1 billion, and these universities are actively seeking additional support. Last year, Harvard launched a capital campaign for another $6.5 billion. Because of the charitable tax deduction, the amount of government subsidy to these institutions in the form of tax deductions is about one out of every $3 contributed.”

The result? “The annual government subsidy to Princeton University, for example, is about $54,000 per student, according to an estimate by economist Richard Vedder,” Reich pointed out. “Other elite privates aren’t far behind. Public universities, by contrast, have little or no endowment income. They get almost all their funding from state governments. But these subsidies have been shrinking.”

More here. [Thanks to Ashutosh Jogalekar.]

“Remembering and Forgetting”: An interview with Viet Thanh Nguyen

Karl Ashoka Britto in Public Books:

Since the 2015 publication of his Pulitzer Prize–winning debut novel The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen has emerged as one of the literary world’s leading public intellectuals. At a time of rising xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiment in the United States and elsewhere, Nguyen’s fiction, academic writing, and media commentary remind us of the need to keep telling the stories that drop out of national narratives, and to remember the histories that the powerful would have us forget. In the following conversation with Karl Ashoka Britto, Nguyen discusses literary form and the representation of violence, the complex dynamics of remembering and forgetting, and the possibility of a politics that could be post-communist without being pro-capitalist.

Since the 2015 publication of his Pulitzer Prize–winning debut novel The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen has emerged as one of the literary world’s leading public intellectuals. At a time of rising xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiment in the United States and elsewhere, Nguyen’s fiction, academic writing, and media commentary remind us of the need to keep telling the stories that drop out of national narratives, and to remember the histories that the powerful would have us forget. In the following conversation with Karl Ashoka Britto, Nguyen discusses literary form and the representation of violence, the complex dynamics of remembering and forgetting, and the possibility of a politics that could be post-communist without being pro-capitalist.

Nguyen is University Professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity and Comparative Literature, as well as the Aerol Arnold Chair of English, at the University of Southern California. In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, he has received many other honors, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a MacArthur Fellowship.

More here.

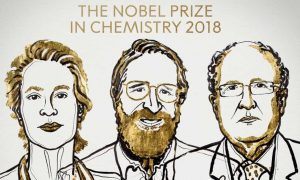

Frances H Arnold, George P Smith and Gregory P Winter win Nobel prize in chemistry

Nicola Davis in The Guardian:

Three scientists have won the Nobel prize in chemistry for their work in harnessing evolution to produce new enzymes and antibodies.

Three scientists have won the Nobel prize in chemistry for their work in harnessing evolution to produce new enzymes and antibodies.

British scientist Sir Gregory P Winter and Americans Frances H Arnold and George P Smith will share the 9m Swedish kronor (£770,000) prize, awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The winners’ work has led to the development of new fuels and pharmaceuticals by making use of nature’s evolutionary processes themselves, leading to medical and environmental advances.

“This is a field that was waiting for a Nobel prize,” said Paul Dalby, professor of biochemical engineering and biotechnology at University College London.

More here.

Academic Grievance Studies and the Corruption of Scholarship

Helen Pluckrose, James A. Lindsay and Peter Boghossian in Areo:

Something has gone wrong in the university—especially in certain fields within the humanities. Scholarship based less upon finding truth and more upon attending to social grievances has become firmly established, if not fully dominant, within these fields, and their scholars increasingly bully students, administrators, and other departments into adhering to their worldview. This worldview is not scientific, and it is not rigorous. For many, this problem has been growing increasingly obvious, but strong evidence has been lacking. For this reason, the three of us just spent a year working inside the scholarship we see as an intrinsic part of this problem.

Something has gone wrong in the university—especially in certain fields within the humanities. Scholarship based less upon finding truth and more upon attending to social grievances has become firmly established, if not fully dominant, within these fields, and their scholars increasingly bully students, administrators, and other departments into adhering to their worldview. This worldview is not scientific, and it is not rigorous. For many, this problem has been growing increasingly obvious, but strong evidence has been lacking. For this reason, the three of us just spent a year working inside the scholarship we see as an intrinsic part of this problem.

We spent that time writing academic papers and publishing them in respected peer-reviewed journals associated with fields of scholarship loosely known as “cultural studies” or “identity studies” (for example, gender studies) or “critical theory” because it is rooted in that postmodern brand of “theory” which arose in the late sixties. As a result of this work, we have come to call these fields “grievance studies” in shorthand because of their common goal of problematizing aspects of culture in minute detail in order to attempt diagnoses of power imbalances and oppression rooted in identity.

We undertook this project to study, understand, and expose the reality of grievance studies, which is corrupting academic research.

More here.

A Short History of U.S. Meddling in Foreign Elections

Oscar: A Life

Anthony Quinn in The Guardian:

Physically unprepossessing – overgrown, clumsy, “slab-faced” – he was nonetheless a magnetic presence, and in his fledgling days in London as high priest of the aesthetic movement he endured chaffing with “remarkable nonchalance”. One gets here the sense of the young Wilde’s talent to annoy as much as to amuse. James Whistler, from whom he learned the art of self-advertisement, eventually turned on him (he had taught his protege too well). To Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne, his other heroes, he was an upstart and a “nobody”. On his year-long lecture tour of the US he didn’t always meet with acclaim, or even a civil welcome – a woman in Washington advised him to “wear your hair shorter and your trousers longer”. Back in London he made an advantageous marriage to Constance Lloyd, an heiress, sired two boys and gravitated to the centre of society’s “swirl and whirl”, borne on his gift for talk and his burgeoning talent as a playwright. Arguably the turning points of his life were twofold: his meeting in 1886 with Robbie Ross, who initiated him in homosexual desire and the dangerous enchantments of a double life, and his later introduction to Alfred Douglas, AKA Bosie, whose vicious feud with his father, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, became the millstones between which Wilde was helplessly ground to dust.

Physically unprepossessing – overgrown, clumsy, “slab-faced” – he was nonetheless a magnetic presence, and in his fledgling days in London as high priest of the aesthetic movement he endured chaffing with “remarkable nonchalance”. One gets here the sense of the young Wilde’s talent to annoy as much as to amuse. James Whistler, from whom he learned the art of self-advertisement, eventually turned on him (he had taught his protege too well). To Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne, his other heroes, he was an upstart and a “nobody”. On his year-long lecture tour of the US he didn’t always meet with acclaim, or even a civil welcome – a woman in Washington advised him to “wear your hair shorter and your trousers longer”. Back in London he made an advantageous marriage to Constance Lloyd, an heiress, sired two boys and gravitated to the centre of society’s “swirl and whirl”, borne on his gift for talk and his burgeoning talent as a playwright. Arguably the turning points of his life were twofold: his meeting in 1886 with Robbie Ross, who initiated him in homosexual desire and the dangerous enchantments of a double life, and his later introduction to Alfred Douglas, AKA Bosie, whose vicious feud with his father, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, became the millstones between which Wilde was helplessly ground to dust.

The story of his fall continues to hold and haunt, enclosing as it does a double mystery. The first is his devotion to Douglas, whose cruelty, recklessness and near-insane bouts of rage threatened to alienate Wilde for good yet never did. Can it be explained? Cyril Connolly thought it was exactly Bosie’s failings – “this invulnerable rival egotism” – that kept Wilde on the hook. He may be right. The second is the enigma of Wilde’s refusal to flee once Queensberry and his hired detectives had him cold and a conviction surely beckoned. “Everyone wants me to go abroad,” said Wilde, seeing no use, “unless one is a missionary…or a commercial traveller”. Sturgis thinks there was a strain of defiance in his staying put, though “inertia” probably contributed, too. He may have been resigned to his fate and become “almost an observer of his own catastrophe”.

More here.

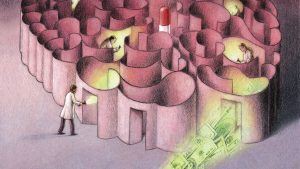

The Alzheimer’s gamble

Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

Baker’s postdoc studies had focused on cellular senescence, the cellular version of aging, which had not yet been linked to Alzheimer’s. But when he gave a drug that kills senescent cells to mice genetically engineered to develop an Alzheimer’s-like illness, the animals suffered less memory loss and fewer of the brain changes that are hallmarks of the disease. Last year, those data helped Baker win his first independent National Institutes of Health (NIH) research grant—not from NIH’s National Cancer Institute, which he once expected to rely on, but from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Bethesda, Maryland. He now has a six-person lab at the Mayo Clinic, working on senescence and Alzheimer’s.

Baker is the kind of newcomer NIH hoped to attract with its recent Alzheimer’s funding bonanza. For years, patient advocates have pointed to the growing toll and burgeoning costs of Alzheimer’s as the U.S. population ages. Spurred by those projections and a controversial national goal to effectively treat the disease by 2025, Congress has over 3 years tripled NIH’s annual budget for Alzheimer’s and related dementias, to $1.9 billion. The growth spurt isn’t over: Two draft 2019 spending bills for NIH would bring the total to $2.3 billion—more than 5% of NIH’s overall budget.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Angelitos Negros

In the film, both parents are Mexicans as white as

a Gitano’s bolero sung by an indigena accompanied by the Moor’s guitar

bleached by this American continent’s celluloid in 1948

when in America the world’s colors were polarized into black & blanco.

In the film, Pedro Infante plays Jose Carlos and sings

Angelitos Negros in a chapel, the film’s title song,

asking the painter of the church’s art to paint a picture with black angels

who look like Jose Carlos’s dark-skinned daughter, a child his wife refuses to accept.

¿Pintor, si pintas con amor, porque desprecias su color

si sabes que en el cielo también los quiere Dios?

Tonight I sing the same song for my morenos absent from these cathedral walls:

O painter, painting with a foreign brush to the rumba of its old bolero.

Listen to our angel’s chorus of inocentes morenos muertos.

We morenos in the barrio create a gumbo quilombo, our little taste of heaven

with matches and propane and coal stones under a pot of cabra y culebras.

We morenos are brown turned black, burnt by fire fired from guardia guns

looking to make us congos for a legisladore’s chanchudos.

Listen to los pelaos in the favelas kicking

around the soccer ball de pie a pie de pie a pie de pie a pie cabeza cabeza

gol!

forced out of their homes by a world class stadium they can never afford to get into,

forced into a life in the prison of their streets.

They too deserve to be painted, pintor, in your fresco Adoration scenes.

¿Pintor, si pintas con amor, porque desprecias su color?

Eartha Kitt sings Pintame Angelitos Negros,

the same Andrés Eloy Blanco poem Infante set to song

on thrift store vinyl playing in homemade YouTube clips.

Kitt raises her voice high enough

to swallow morning if it does not give her a sky

with dark-skinned angels in its clouds tonight.

Then dusk falls over the continent built on

shadows, shackles, and shame.

Broken-winged Blackbird three shades of jade, just fly into dark matter in outer space.

Perhaps up there is a better painter, better god for us all to obey.

by Darrel Alejandro Holnes

from Split This Rock

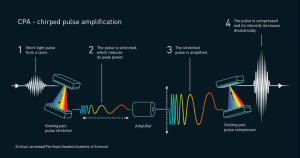

Nobel Prize In Physics 2018: How To Make Ultra-Intense Ultra-Short Laser Pulses

Chad Orzel in Forbes:

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics was announced this morning “for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics.” This is really two half-prizes, though: one to Arthur Ashkin for the development of “optical tweezers” that use laser light to move small objects around, and the other to Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland for the development of techniques to make ultra-short, ultra-intense laser pulses. These are both eminently Nobel-worthy, but really aren’t all that closely related, so I’m going to split talking about them into two separate posts; this first one will deal with the Mourou and Strickland half, because I suspect it’s the less immediately comprehensible of the two, and thus probably needs more unpacking.

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics was announced this morning “for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics.” This is really two half-prizes, though: one to Arthur Ashkin for the development of “optical tweezers” that use laser light to move small objects around, and the other to Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland for the development of techniques to make ultra-short, ultra-intense laser pulses. These are both eminently Nobel-worthy, but really aren’t all that closely related, so I’m going to split talking about them into two separate posts; this first one will deal with the Mourou and Strickland half, because I suspect it’s the less immediately comprehensible of the two, and thus probably needs more unpacking.

What Mourou and Strickland did was to develop a method for boosting the intensity and reducing the duration of pulses from a pulsed laser. This plays a key role in all manner of techniques that need really high intensity light, from eye surgery to laser-based acceleration of charged particles (sometimes touted as a tool for next-generation particle accelerators), or really fast pulses of light such as recent experiments looking at how long it takes to knock an electron out of a molecule. This kind of enabling of other science is exactly the kind of thing that the Nobel Prize ought to recognize and support, so I think this is a great choice for a prize.

More here.

Deborah Eisenberg, Chronicler of American Insanity

Giles Harvey in the New York Times:

It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?”

It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?”

Behind her desk is a wrought-iron daybed on which she takes frequent breaks to read; while she’s in the early stages of working on a new story, two hours of writing a day is usually as much as she can manage. When I asked her what she does with the rest of her time, a puzzled look came across her face, as though she were trying to decipher some hidden message in the ceiling moldings. “It’s hard to say,” she eventually conceded.

More here.

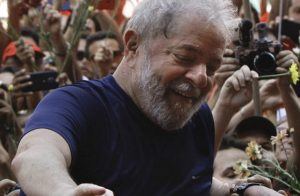

Noam Chomsky: I just visited Lula, the world’s most prominent political prisoner

Noam Chomsky in The Intercept:

Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.

Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.

My wife Valeria and I have just visited a prison to see arguably the most prominent political prisoner of today, a person of unusual significance in contemporary global politics.

By the standards of U.S. prisons I’ve seen, the Federal Prison in Curitiba, Brazil, is not formidable or oppressive — though that is a rather low bar. It is nothing like the few I’ve visited abroad — not remotely like Israel’s Khiyam torture chamber in southern Lebanon, later bombed to dust to efface the crime, and a very long way from the unspeakable horrors of Pinochet’s Villa Grimaldi, where the few who survived the exquisitely designed series of tortures were tossed into a tower to rot — one of the means to ensure that the first neoliberal experiment, under the supervision of leading Chicago economists, could proceed without disruptive voices.

Nonetheless, it is a prison.

More here.

Fascinating talk by Frank Abagnale, whose story was told in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Catch Me If You Can”

Physics Nobel prize won by Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland

Ian Sample and Nicola Davis in The Guardian:

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

The American physicist Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou from France, and Donna Strickland in Canada will share the 9m Swedish kronor (£770,000) prize announced by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm on Tuesday. Strickland is the first female physics laureate for 55 years.

Ashkin, an affiliate of Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, wins half of the prize for his development of “optical tweezers”, a tractor beam-like technology that allows scientists to grab atoms, viruses and bacteria in finger-like laser-beams. The effect was demonstrated by the award committee by levitating a ping pong ball with a hairdryer.

Mourou at the École Polytechnique near Paris, and Strickland at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, each receive a quarter of the prize for work that paved the way for the shortest, most intense laser beams ever created. Their technique, named chirped pulse amplification, is now used in laser machining and enables doctors to perform millions of corrective laser eye surgeries every year.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Lazarus in Varanasi

FROM A PYRE on the burning ghat

As if remembering something important.

As if to look around one more time.

As if he has something at last to say.

As if there might be a way out of this

.

by Joseph Stroud

from Narrative Magazine

Winter 2008

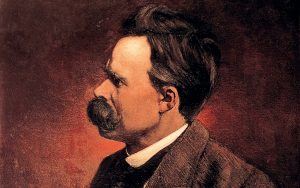

The agony and the destiny: Friedrich Nietzsche’s descent into madness

Ray Monk in New Statesman:

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

In the chapter on Nietzsche in his History of Western Philosophy, published in 1946, Bertrand Russell went some way towards correcting some of these Nazi-led misunderstandings, emphasising that Nietzsche was far from being a nationalist, a racist, a worshipper of the state, or a German supremacist (his writings are in fact full of anti-German sentiment). Russell, however, could not free himself from his times sufficiently to avoid misrepresenting Nietzsche’s notion of the will to power. Nietzsche’s ethic, Russell claims, can be summed up by saying: “Victors in war, and their descendants, are usually biologically superior to the vanquished. It is therefore desirable that they should hold all the power, and should manage affairs exclusively in their own interests.” Russell’s chapter ends with a statement that has often been quoted and which helped to shape Nietzsche’s reputation among English-speaking people for a generation: “I dislike Nietzsche because he likes the contemplation of pain… because the men whom he most admires are conquerors, whose glory is cleverness in causing men to die.”

More here.

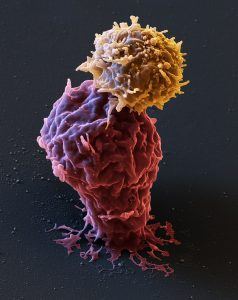

Breakthrough Leukemia Treatment Backfires in a Rare Case

Denise Grady in The New York Times:

A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

The researchers noted that the case confirms a longstanding hypothesis: It takes just one malignant cell to give rise to a deadly cancer. Their report was published on Monday in the journal Nature Medicine. At first, the patient had a complete remission. But at the same time, that single enemy cell was multiplying uncontrollably, into billions of leukemia cells that caused a relapse nine months later and ultimately killed him. His cells were engineered at the University of Pennsylvania, where the treatment, called CAR-T therapy, was developed in collaboration with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the drug company Novartis. The treatment was experimental, and he was part of a study. Researchers say that the case was a rare event, never seen before, and that there is no evidence of this problem in cells engineered by Novartis, other drug companies or other research centers.

More here.

What Exactly is Neo-Liberalism and What’s Wrong with It?

by Pranab Bardhan

My last column was about populism. One group populists invariably dislike are the ‘liberals’—the despised L-word in American politics. Some of the same people are often despised also by the Left all over the world as ‘neo-liberals’. It is not always easy to know who the latter are, as the word is used in different senses by different critics. Of course, keeping the term ill-defined and coarse serves the critics, as larger targets always make shooting practice easier.

My last column was about populism. One group populists invariably dislike are the ‘liberals’—the despised L-word in American politics. Some of the same people are often despised also by the Left all over the world as ‘neo-liberals’. It is not always easy to know who the latter are, as the word is used in different senses by different critics. Of course, keeping the term ill-defined and coarse serves the critics, as larger targets always make shooting practice easier.

Does ‘neo-liberalism’ stand for market fundamentalism? Except for some cranks, there are not that many of strict market fundamentalists in intellectual circles or among political leaders. If Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek are considered the economist high-priests of neo-liberalism, it is important to remember that Friedman advocated a substantial negative income tax for the poor and Hayek talked about a basic ‘floor income’ for everybody undergirding his version of the liberal economy. In politics neither Margaret Thatcher nor Ronald Reagan could (or even really attempted to) get rid of a significant welfare state and social security.

Sometimes my leftist friends dislike neo-liberalism because it is pro-capitalist. But they are often friendly with Keynesians. After all Keynes, while showing the limitations of market mechanism in solving the problem of mass unemployment, was essentially pro-capitalist in his role as savior of capitalism, and openly dismissive (unduly so) of Marx. “The Class War”, he once wrote, “will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie”. Keynes was not neo-liberal, was he?

Matters are made even more complicated by many public policy thinkers who are pro-market, but not necessarily pro-business. This tradition actually goes back to Adam Smith. There are many passages in the Wealth of Nations that can be interpreted as being in favor of free markets but definitely against prone-to-collude business magnates. Read more »