by Joshua Wilbur

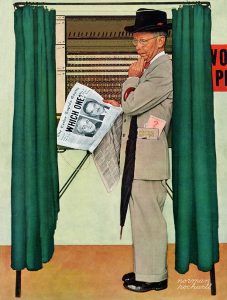

This past Tuesday—September 25th 2018—was “National Voter Registration Day” in the United States. I didn’t register to vote on September 25th, and I’m not registered to vote as I write this now.

I’m not proud of the fact. Far from it, I feel intensely guilty when I imagine some upstanding acquaintance asking me, “Are you registered to vote yet?”, so that I am forced to stammer through an explanation as to why not. (The alternative in this scenario would be to lie, to simply say “Yes,” which many people do when questioned about voting habits. It is shameful to have done nothing on election day, but, even still, our society imparts no immediate negative consequences on non-voters, and no one knows who actually voted and who did not.)

But I’ll admit it openly: I’m not registered to vote because my printer is out of ink.

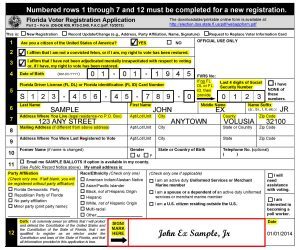

You see, I recently moved to a new address in a different state. The county must be made aware of my presence here if I am to be added to the electoral roll. Thirty-seven states allow online voter registration, but, unfortunately, my new home state is not one of them. This means that I must print, complete, and mail a form to the “County Commissioner of Registration” at least twenty-one days prior to Election Day on November 6th.

This is mildly annoying, a minor inconvenience. It doesn’t deserve mention alongside the history of American voter suppression in all its contemptible forms, beginning with poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests in the Jim Crow South and persisting in the guises of photo ID laws, district realignment, felony disenfranchisement, and voter purges, to name just a few contemporary tactics.

No one is actively trying to suppress my vote. I have a problem with my printer. I just need to order some ink (and I guess a box of envelopes), print the form, fill out the form, put it in the envelope, seal the envelope, walk a few blocks, and drop it in a mailbox. It really isn’t that difficult.

*****

For a long time, democracy was a dirty word. Rule (kratos) of the people (demos) first surfaced in ancient Athens, where, in spite of its radical innovations, the democratic experiment was subject to corruption and fits of passion. In the minds of many ancient observers, democracy was no more than collective tyranny. Plato famously denounced “the mob” as capricious and ignorant.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, who admired classical philosophy and published under Greek and Roman pseudonyms (e.g., Brutus and Publius in the Federalist Papers), were also wary of the mob. In Federalist 10, Madison described the dangers of a direct democracy governed by the people: “A pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction.”

The majority cannot be trusted to pursue the common good. Public opinion is fickle and ill-informed—Walter Lippmann’s Public Opinion, published in 1922, remains as relevant as ever on the issue of mass-delusion. The workings of government are too complex, too elaborate, to be guided by the will and whims of the people.

And so we live in a representative democracy, a democracy of elected delegates. As described in the Declaration, ours is a government which derives it power from “the consent of the governed.” The few represent the many. Presidents, congressmen, senators, governors, mayors, local officials—in the purest vision, all representatives are united in their pursuit of the public good and their protection of our inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. (“Yeah right,” we think to ourselves).

It goes without saying that the times could be happier. There’s worry in the air, a feeling that our own democratic experiment is no longer working (and it’s debatable to what extent and for whom it’s worked previously). In recent (i.e., post-Trump) years, a nervous flurry of books has gathered around the idea that Western democracy is in decline. These works include The Retreat of Western Liberalism by Edward Luce, The Once and Future Liberal by Mark Lilla, The Monarchy of Fear by Martha C. Nussbaum, How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, and Why Liberalism Failed by Patrick J Deneen.

This is a reading list for a masochist. I’ve read most of the above titles, and, in each case, I felt more helpless, more pessimistic by book’s end. The themes are familiar but no less troubling for having been said again and again.

Where to begin?

Of course, individualism prevails: we are “bowling alone,” as Robert Putnam wrote nearly twenty years ago, a practical eon given the advent of social media and the smartphone. We’re more enamored with private pleasures than ever before. Americans are siloed from each other, secure in our homes, our workplaces, our cars, our social networks, and our increasingly medicated minds. This is literal “division.”

All forms of organization are met with skepticism. Long running surveys demonstrate a lack of confidence in virtually every American institution: news media, organized labor, big business, the healthcare industry, the education system, and, of course, government. A report from the Pew Research Center shows that, between 1958 and 2015, public trust in the federal government fell from about 73 to about 19 percent, an astonishing statistic.

All the while, old problems persist: economic inequality, political stagnation, failing schools, burgeoning prisons, ongoing and worsening environmental crisis. I hardly need to cover everything; most of us know the score. What, then, can be done?

The best answer is a common refrain.

“If you want things to change, then vote!”

It’s trite but true. Voting changes the playing field. Voting is the difference between Andrew Jackson or Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln or Stephen Douglas, Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton. Elections at the local, state, and national levels have meaningful repercussions for what goes on in our schools, hospitals, businesses, and communities at large.

Even still, many Americans (from the left and the right) believe voting to be a fool’s game or a false choice. Republican or Democrat, they’re all the same, wealthy cronies who protect the status quo.

It’s a valid criticism. But to discount the merits and possibilities inherent to the act of voting represents a serious failure of imagination. In surveying the literature around “democracy’s decline,” I’ve been surprised at how few pages are dedicated to the voting problem. I don’t mean the problem of who we vote for—on this subject, there’s no shortage of commentary—but how we vote and how many of us vote.

To vote is to exercise your fundamental right as a democratic citizen. When the Greeks spoke of the barbarians, they meant to suggest a fundamental difference between those who choose freely and those who live under tyranny. In other words, if we genuinely believe in democracy, then it is the vote that makes us who we are. It’s also a precondition for addressing our well-documented ills. Before dealing with climate change, income inequality, crumbling infrastructure, poor healthcare, etc., we must have a well-functioning mechanism for selecting the leadership whose job it will be to address these issues among many others. It’s a matter of not only tackling the right problems but doing so in proper order. I can’t emphasize this point enough.

Unfortunately, the reality of voting is stark. For a country that prides itself on its democratic spirit and free elections, the United States is awful about voting. Turnout statistics paint a bleak picture. The percentage of the voting-age population that actually votes tends to fall between fifty and sixty percent. According to the Pew Research Center, the United States trails most developed countries in voter turnout, placing 26th out of 32 OECD nations. Turnout varies widely state-to-state, the result of differences in laws, procedures, and populations. Some Americans vote using paper ballots; others vote using electronic machines; some even vote at home, avoiding the polls altogether. And, for many holders of political office, there isn’t much incentive to expand the number of voters, so reforms are slow-moving and piecemeal.

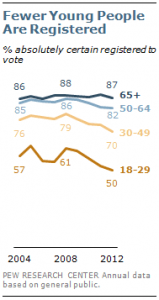

What’s most troubling, though, is the youth vote. Voters under forty are out-voted by their older peers in virtually every election at every level of government. In the 2014 midterms, voters under the age of forty comprised 26% of the electorate. Think about that: for every vote cast, only one out of four was by an American born after 1974. That’s more than disturbing; it’s a blaring signal (though hardly a new one) that our democracy is broken.

Why don’t young Americans vote?

Is it transience, the fact that young people move more often?

Is it disillusionment with political process?

Or is that we simply don’t know how to vote?

******

This morning, I logged into my Amazon Prime account, clicked the search bar, and typed, “HP Deskjet 2540 Printer Ink.” More than two hundred results populated, but I felt comfortable surveying only the first page. The top result was Prime Eligible and labeled as “Amazon’s Choice,” so I clicked and began scrolling through the top reviews. (There are more than 4,000 reviews for this particular ink cartridge).

I wanted to be certain that the cartridge is compatible with my printer, so I was relieved to see “amazon-confirmed-fit” at the top of the item page, a feature that allowed me to input my model number and confirm that, yes, “This fits Deskjet 2540.”

I added the item to my cart. I also added envelopes and a box of protein bars. I confirmed my address and placed the order. It arrives in two days.

******

October’s issue of The Atlantic asks the question, “Is Democracy Dying?” The magazine’s essays touch on all manner of -isms: racism, populism, cynicism, globalism, despotism. As with the books I touched on above, the tone is largely pessimistic. Our democracy is wilting, if not dying, though arguably our means of governance has always been closer to a technocracy or oligarchy, so it’s fair to ask to what degree our democracy has ever been truly “alive.” (As you can tell, there’s no lack of terms, metaphors, and concepts to debate.)

In reading the issue, I especially appreciated an essay by Yoni Appelbaum: “Americans Aren’t Practicing Democracy Anymore.” Appelbaum argues that Americans have become less civically engaged in all aspects of life—not just voting at the polls every two years—and the result is mass confusion about the purpose of government and how it relates to our private lives. Appelbaum opens with a useful reminder:

“Democracy is a most unnatural act. People have no innate democratic instinct; we are not born yearning to set aside our own desires in favor of the majority’s. Democracy is, instead, an acquired habit. Like most habits, democratic behavior develops slowly over time, through constant repetition. For two centuries, the United States was distinguished by its mania for democracy: From early childhood, Americans learned to be citizens by creating, joining, and participating in democratic organizations. But in recent decades, Americans have fallen out of practice, or even failed to acquire the habit of democracy in the first place.”

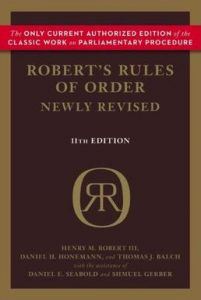

Appelbaum makes a compelling case that America was once a place defined by its wealth of associations, committees, voluntary organizations, churches, councils, unions, fraternities, and so on. These institutions still exist, of course, but they are severely diminished. With their diminishment comes a generation (of which I am a part) that knows very little about cooperation and debate, rules of order and matters of administration.

We’re bad at democracy because we are out of practice. Our “public sphere,” as Habermas called certain forms of social life, has moved to Twitter. We won’t feel the full effects of this transformation for many years, but the early symptoms are becoming impossible to ignore.

Applebaum sums up the current state of affairs:

“The golden age of the voluntary association is over, thanks to the automobile, the television, and the two-income household, among other culprits. The historical circumstances that produced it, moreover, seem unlikely to recur; Americans are no longer inclined to leave the comforts and amusements of home for the lodge hall or meeting room. Which means that any revival of participatory democracy won’t be built on fraternal orders and clubs.”

Applebaum, following the example of John Dewey, goes on to suggest that improving civic education is our best hope of shaping a new generation of good democrats. Students must learn to self-govern from a young age. This seems right to me, though I worry about what it means for Millennials (those of us born between 1981 and 1996) and Post-Millennials (those of us born in the late 1990s through the present day). Having missed out on meaningful educational interventions, are these citizens simply beyond hope, generations who missed out on political action?

Surely not.

Just thinking about my own circle of friends and family, I know plenty who are passionate about the common good. People care, but they lack a sustained channel for their political energy. They know what their beliefs are, but they don’t know how and where to act.

To give a brief example, my younger (by about a decade) sister is in high school. She and her friends have participated in a number of political marches, including the Women’s March in early 2017. She understands the big issues and holds well-reasoned positions. We’ll discuss what’s in the news and debate the finer points.

That said, we’re both confused about the details. How does the Electoral College work, and why does it exist? Why can’t people just vote online? Why are there only ever two political parties in power? We don’t understand it.

A few weeks ago my sister and her friends wanted to order a pizza—(they eat a lot of pizza). Typically, they use a smartphone app to place and track the order. The app remembers your preferences, so that the whole process takes mere seconds. But, on this sad occasion, the app wasn’t working. The group came to me with an earnest request.

Would I please call the restaurant and order the food?

None of them wanted to talk on the phone. They had never called in a delivery before.

This interaction shouldn’t be taken too seriously, but I do wonder about how my generation—and my sister’s generation—are now responding to the simplest forms of resistance or friction. Our lives are mediated through a series of apps, web portals, automated programs, digital trackers, rating systems, and, of course, the screens which make it all possible. Our nation’s youngest eligible voters have never known any other way of life.

If ordering a pizza over a phone call provokes anxiety in today’s teenagers, then imagine how intimidating it will be for them to register to vote, to inquire about a polling place, to stand in a long line, and to fill out a paper ballot that features the names of unknown politicians. There’s nothing inviting about voting. As straightforward as it may seem to older voters, the electoral process in America is too difficult. Or more precisely: it feels too difficult, and that’s what ultimately counts.

This, to me, is a principal flaw of our electoral system and a major reason why young people avoid the polls: voting is off putting and entirely divorced from the comfortable flow of our everyday lives. Our culture is now in the very lucrative business of rendering everything convenient—from shopping to traveling to eating to learning. And the cliches about instant gratification and unerring distraction are unfortunately true. So much of contemporary life is easy, predictable, and designed to make us fleetingly happy via the magic of dopamine-granting reward loops. Elections, on the other hand, are rare and arcane events; to Millennials like me, they are shrouded in mystery.

How do we fix this?

First, upon reaching eligibility, voters should be automatically registered in all fifty states. If you interact with a government agency, you’re registered to vote unless you choose to “opt-out.” Other countries, such as Germany and Sweden, enjoy significantly higher voter turnout because they employ such systems of automatic enrollment.

Elections should also be held on a national holiday, or, alternatively, on the weekend. No one should be unable to vote because of their situation at work.

It’s a controversial idea, but online voting should be aggressively pursued. There are serious concerns about fraud, but we’re kidding ourselves if we doubt that online voting is the inevitable future. It’s early days for blockchain voting, but the technology offers some solutions to much-feared security issues. In the meantime, vote-at-home measures are a reasonable and effective way to make voting more readily intelligible and convenient.

(I would add here that I’ve never understood the argument that voting should be difficult in order to dissuade the uninformed. Elitist overtones aside, doesn’t this line of reasoning overlook an obvious and more democratic solution? Inform them.)

Finally, those technology and media companies which dominate our attention—not just Facebook, Apple, Netflix, and Google (the FANG stocks) but the entire culture industry— should find creative ways to bring democracy into the purview of daily life. Social media outlets, in particular, could take great advantage of location data to provide users with useful information about what’s happening in their communities, who is up for election, and where and how to vote.

These suggestions are only partial solutions. Changing our relationship to voting is an immense task. It’s now conceivable that a person could go from cradle to grave without having ever voted for anything in his or her life. What’s more worrisome is how unfazed we are by such a glaring contradiction between our ideals and our reality. How can we “achieve our country,” to borrow Richard Rorty’s memorable phrase, in the age of distraction? How can we make democracy enticing? We should obsess over this last question; everything else is secondary.

*****

Once the ink arrives and the form is submitted, I’ll be registered to vote. Between now and election day, I plan to do some serious research. I’ll take an hour—maybe two—to study the ballot, learn about the candidates, and consider the measures. I know nothing about the school board or municipal government, but I’ll try to learn as much as I can before voting.

I’m still not sure where my polling place is located. I’ve tried to use a lookup on the state website, but I receive an error message: “No Record Found”. I assume that I must be registered before the system can direct me. In the meantime, it says to “Contact your county board of elections for polling place location.”

A phone call, in other words.