by Carol A Westbrook

“Take two aspirin and call me in the morning” has been replaced by “Here’s a bottle of oxycodone. Don’t call me for a month.”

Two million Americans are addicted or dependent on opioid drugs. Last year, 72,000 of them died of overdoses, usually by accidentally taking too high a dose of an illicit drug. What has caught our attention is that these deaths are not the down-and-out, indigent drug addicts sprawled in dirty crack houses that are pictured on TV crime shows. They are our friends and family, teenagers and adults who unwittingly became addicted to medication that was legitimately prescribed to them by doctors.

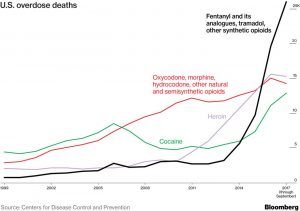

Drug overdose deaths are rapidly increasing, as is apparent from the chart below, and are now the leading cause of deaths in adults under age 50. The cause of this epidemic is not drug pushers, or dirty needles, but the health care industry itself. It is the result of a series of well-meaning but misguided policy changes that appeared over the last twenty years that physicians such as myself were asked to implement in caring for patients with pain. Let me explain.

Narcotics include opium derivatives such as morphine, heroin, codeine, oxycontin, and synthetics like fentanyl. They are the most effective painkillers known, but they are also the most addictive because of their side effects. In addition to stopping pain, they increase the body’s level of dopamine, a hormone that provides a sense of happiness. Narcotics also slow bodily functions, including breathing, bowel movements, and alertness. With frequent use the body gets adjusted to these side effects. Then, when the medication wears off, the pain returns, and the other effects are reversed There will be an overwhelming desire to increase the dopamine levels again, and also to stop the sickening effects of withdrawal: diarrhea, shaking, restlessness, insomnia, fevers and rapid breathing. The drive to stop these symptoms is all consuming. On the other hand, too high a dose and breathing stops, resulting in death from overdose.

Because of the risk of addiction and death, and the need for careful dosage, doctors did not routine prescribe opioid painkillers prior to the year 2000. Narcotics were reserved to treat severe post-operative pain, cancer pain, or battlefield wounds. But a series of well-meaning policy decisions by the health care industry led to a change in doctors’ behavior beginning in about 1999, This was the result of two highly-publicized lawsuits in the 90’s, James v Hillhaven Corpin 1991 and Bergman v. Chin, 1999, in which patients’ families received large settlements for the failure of their doctor to provide adequate pain relief. Doctors were under pressure to prevent future lawsuits for neglecting pain. In a move to prevent additional hospital lawsuits, the Joint Commission, the major accreditation board for all US hospitals, mandated aggressive pain control as a guiding treatment principal. In 2000 they released a “Patients’ Bill Rights,” which included the right of patients to the appropriate assessment and management of their pain.

Suddenly it became the legal duty of physicians to relieve pain and suffering. Prescribing opioid painkillers was the easiest route to take. This left many doctors unprepared, having neither the experience nor training to use narcotics or other methods to treat chronic pain in the outpatient.

The pharmaceutical industry saw this as an opportunity to develop and aggressively market new pain pills that were convenient to take, longer lasting, and did not require injection. Oxycontin, made by Purdue Pharma, was one of the most widely used. Oxycontin was a slow-release formulation of a partially synthetic opium, oxycodone. Because of the slow release there would be no “high,” and in theory this would make the pills less prone to misuse; in reality the pills could easily be crushed and used like any other narcotic. Nonetheless, Oxycontinwas marketed as being less addictive. Due to this deceptive marketing, oxycontin quickly became the most widely-prescribed narcotic drug in the US.

Although every doctor learned in medical school that all narcotics are addictive, most desperately wanted to believe what Purdue Pharma was telling them — that oxycontin was a safe, virtually non-addictive drug. This, then, was an easy answer to the flood of patients demanding pain medication. Doctors gave out pain pills like candy. At about the same time, “patient satisfaction ratings” were beginning to appear as determinants of doctors’ salaries, further increasing the pressure on them to fill their patients’ requests for prescription painkillers. The number of addicts began to increase even in normal Americans with mild health conditions, with a corresponding increase in the number of accidental overdoses. The increased deaths caught the attention of the Justice Department, who sued Purdue Pharmaceuticals in 2007 for deceptive advertising. Purdue was fined $630 million, and took the drug off the market. Doctors were now under pressure to stop prescribing narcotics.

Suddenly the pendulum shifted. By this time, many patients were dependent on narcotic painkillers, but could no longer rely on their doctor to prescribe them. Some turned to illegal suppliers who stockpiled prescription drugs, others turned to heroin, which was cheaper and more accessible. In 2008, just one year after the Purdue lawsuit, the number of deaths from heroin started to skyrocket, as you can see in the chart below.

Things only got worse when fentanyl appeared on the black market. Fentanyl has a legitimate medical use, but it is very potent and must be carefully dosed. Because it is fifty times stronger than heroin, the risk of inadvertent, accidental overdose is high, especially when it is unknowingly mixed with heroin. As the availability of fentanyl increased so did drug overdoses. Black market fentanyl is not made by legitimate pharmaceutical companies, but is produced in China and sold on the Internet.

China allowed international commerce via the Internet starting about 2010 with the launch of its browser service, AliBaba. It took only a few short years for entrepreneurs to recognize fentanyl to be a highly profitable product that is easily produced and inexpensive to ship due to its low weight. Because it is completely synthetic, it does not require opium plant-derived materials in its production, so there is no reliance on the cartels that control opium distribution. As you can see in the chart below, overdose deaths from fentanyl began to skyrocket in 2013, when it became widely available to dealers via the Dark Web.

Two million addicts without legal access to prescription narcotics but with a ready supply of inexpensive fentanyl–the results are predictable: overdose deaths in alarming numbers. Opioid deaths are now considered a major health crisis, and the government is responding. Several initiatives were put into place within the last couple of years. The National Institutes of Health launched the HEAL initiative (Helping to End Addiction Long-Term), outlining a policy and priorities similar to what I am covering here, as well as development of novel drugs fro treatment or narcotic replacement. HEAL has a $500 million budget for 2018. SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration), an agency of Health and Human Services, is providing $930 million in state grants to support prevention, treatment and recovery support services to individuals with opioid use disorder. The President’s initiative includes limiting the production and prescription of narcotic medications, and cutting off the illegal supply of drugs crossing the borders.

These efforts may seem commendable, but in reality they will have little impact. Limiting the legal supply of narcotics will go a long way to preventing new addictions, but it will not help the existing patients with opioid use disorder. This process will lead to more overdose deaths as people turn to illegal substances. The HEAL and SAMSA grants have the right idea, but the total budgets amount to less than $1,000 per addict, with much of that going toward research. These won’t go very far in covering the cost of inpatient treatment in a rehab facility, for example, which is about $5,000 for a 3-month stay, and maintenance methadone alone costs $4,000 per year.

Who is going to pay these costs? The health care industry is the cause of this drug overdose epidemic and has made billions of dollars in profits by servicing it, including drug sales and clinical services. I maintain that the industry must take both professional and financial responsibility for ending it. Here is how to do it.

First of all, we need to regard addiction as a lifelong disease, not a crime, and treat it medically. Most of the current addicts would do anything to stop their habit and get back to normal life, but it is virtually impossible to do so on their own. We need many more treatment centers to help them get off narcotics or onto maintenance drugs such as methadone or suboxone. There are less than 15,000 such treatment centers in the US, to manage over two million people with opioid use disorder! The long waiting time is unconscionable. The Joint Commission for hospital accreditation should mandate an addiction treatment center in every hospital, even if it is not a profit center.

Pain is generally the reason for that first narcotic prescription, and will continue to be the cause of new addictions or of relapse for recovering addicts. The medical profession seems to have forgotten that twenty years ago we used to treat chronic pain without resort to narcotics. Ironically, there are so many more treatments than there were then. There are more effective partial joint replacements, newer anti-arthritis drugs, nerve blocks, joint injections, electrical stimulation, physical therapy, surgery, yoga and meditation. Even a stable low dose of a long-acting narcotic, such as methadone, is sufficient to treat chronic pain if it is carefully supervised. Pain management clinics can do this, but they are desperately low in numbers and understaffed. The waiting lists are long access to these treatments may be limited to those with insurance. Hospital systems need to take responsibility for establishing these clinics and insuring they are properly staffed and subsidized as needed.

The pharmaceutical industry, which profited so much from selling opioid medications, must bear the cost of providing the medications necessary to treat addiction, such as methadone, suboxone, and naloxone, at reasonable cost.

Most importantly, treatment of chronic pain needs compassion and understanding. It’s all too easy to give a patient pain pills to get him out of your clinic. Doctors need to be willing to invest the time and energy it takes to alleviate suffering. This is, of course, why we became physicians in the first place.