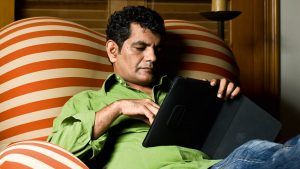

Shahnaz Siganporia in Vogue:

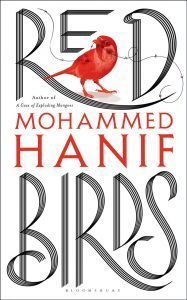

‘Red Birds’ marks the award-winning British-Pakistani author’s return to fiction after seven years, and is a potential instant classic.

‘Red Birds’ marks the award-winning British-Pakistani author’s return to fiction after seven years, and is a potential instant classic.

“We used to have art for art’s sake; now we have war for the sake of war” reads a line from Mohammed Hanif’s latest novel, Red Birds. Writers have relentlessly written about war, and Hanif’s latest will probably go on to join the best in this canon. His is a satire of our age—of money-making schemes in forgotten camps, electrocuted mongrels, lost men, and the women left behind in asymmetrical wars. It’s specific, relevant to the violence we know in headlines and hashtags, but generously buttressed in the universal absurdity of life and death. Witty, eviscerating in its irony and sneeringly insightful, this novel is packed with what we’ve come to recognise as Hanifian trademarks. A recommended read of the season, the writer and journalist shares his experience of writing this novel, battling censorship and understanding his feminist gaze.

Of all the characters in Red Birds, a large chunk of the narrative is by Mutt. What made you light up the narrative from the point of view of a dog?

Like most people who spend a lot of time around dogs, I tend to talk to them occasionally. And then sometimes they talk back, if not through words, through their gestures, humps and licks. Municipalities around many places in the world carry out a cull of stray dogs for public safety. It’s a bit like powerful countries always having the need to have a war at a distant place that makes them feel safer in their suburban homes. I often think that if dogs ran our cities we might be better off. I was really reluctant to give Mutt a voice, but he insisted. In the end, Mutt gets what he wants or dies trying.

More here.

During the slow recovery after the 2008 financial crisis, Larry Summers, the Director of President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council, argued that the US economy was in the grips of “secular stagnation”: neither full employment nor strong growth could be achieved under stable financial conditions.

During the slow recovery after the 2008 financial crisis, Larry Summers, the Director of President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council, argued that the US economy was in the grips of “secular stagnation”: neither full employment nor strong growth could be achieved under stable financial conditions. Our understanding of heredity and genetics is improving at blinding speed. It was only in the year 2000 that scientists obtained the first rough map of the human genome: 3 billion base pairs of DNA with about 20,000 functional genes. Today, you can send a bit of your DNA to companies such as

Our understanding of heredity and genetics is improving at blinding speed. It was only in the year 2000 that scientists obtained the first rough map of the human genome: 3 billion base pairs of DNA with about 20,000 functional genes. Today, you can send a bit of your DNA to companies such as  That the news in its traditional forms is the problem with journalism actually dawned on me much earlier, when in 2006 I joined the editorial department of a major Dutch newspaper. I was 24 and studying philosophy when I landed a job covering domestic affairs. As a philosophy student does, I immediately started asking: what is this thing called news that I’m supposed to make here? Scrutinizing the practices of my colleagues, I eventually distilled a definition that I think describes news pretty accurately.

That the news in its traditional forms is the problem with journalism actually dawned on me much earlier, when in 2006 I joined the editorial department of a major Dutch newspaper. I was 24 and studying philosophy when I landed a job covering domestic affairs. As a philosophy student does, I immediately started asking: what is this thing called news that I’m supposed to make here? Scrutinizing the practices of my colleagues, I eventually distilled a definition that I think describes news pretty accurately.

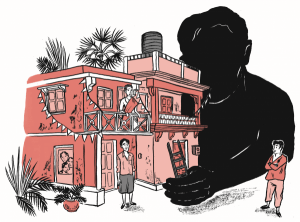

Filmistan Studios occupies five acres in Goregaon, India, which is technically an outer suburb of Mumbai, but denser than most New York City neighborhoods. If you take the train from the city proper and fight the foot traffic that crowds the bazaar area around the station, you’ll reach a pair of steel gates. Just on the other side are Filmistan’s soundstages, which have been in continuous operation since 1943. In the Golden Age of Hindi Film, up to the 1960s, the industry worked along lines similar to those of the old Hollywood studio system, with each production house fielding its own stable of talent. Unlike most of its former rivals, Filmistan has remained open for business as a production facility, and the grounds now accommodate eight stages and several outdoor shooting areas, including a Hindu temple, a jailhouse exterior, and a village. But Filmistan is more than a collection of sets. Behind the scenes, there are real people living there. I came to Filmistan as an anthropologist in training, with a research project that looked solid enough, on paper, to win a Fulbright grant. One thing about ethnography they don’t teach you in school, though, is how awkward it can be getting started. Reaching out to people to do research with—soliciting “informants”—can feel like approaching strangers for a date. Left to myself in Mumbai, with my sun-glasses and clumsy Hindi, I was a field-work wallflower

Filmistan Studios occupies five acres in Goregaon, India, which is technically an outer suburb of Mumbai, but denser than most New York City neighborhoods. If you take the train from the city proper and fight the foot traffic that crowds the bazaar area around the station, you’ll reach a pair of steel gates. Just on the other side are Filmistan’s soundstages, which have been in continuous operation since 1943. In the Golden Age of Hindi Film, up to the 1960s, the industry worked along lines similar to those of the old Hollywood studio system, with each production house fielding its own stable of talent. Unlike most of its former rivals, Filmistan has remained open for business as a production facility, and the grounds now accommodate eight stages and several outdoor shooting areas, including a Hindu temple, a jailhouse exterior, and a village. But Filmistan is more than a collection of sets. Behind the scenes, there are real people living there. I came to Filmistan as an anthropologist in training, with a research project that looked solid enough, on paper, to win a Fulbright grant. One thing about ethnography they don’t teach you in school, though, is how awkward it can be getting started. Reaching out to people to do research with—soliciting “informants”—can feel like approaching strangers for a date. Left to myself in Mumbai, with my sun-glasses and clumsy Hindi, I was a field-work wallflower R

R Alvinella pompejana, a type of deep sea worm, can thrive at temperatures that would kill most living organisms. It has been used in skin creams — and sequences of its genes appear in 18 patents from not only BASF, but also a French research institution. Genetic prospectors — a term some find offensive, while acknowledging there’s not a great alternative — have a range of motivations. Some are hoping to develop a novel treatment for cancer. Others want to create the next Botox. Most are looking for organisms with exceptional traits that might offer the missing piece in their new product. That is why patents are filled with“extremophiles,” known for doing well in extreme darkness, cold, acidity and other harsh environments, said Robert Blasiak, a researcher from the Stockholm Resilience Centre who was involved in the patent study.

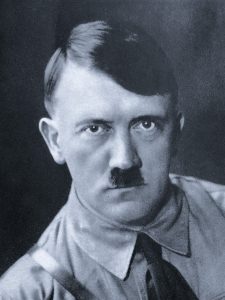

Alvinella pompejana, a type of deep sea worm, can thrive at temperatures that would kill most living organisms. It has been used in skin creams — and sequences of its genes appear in 18 patents from not only BASF, but also a French research institution. Genetic prospectors — a term some find offensive, while acknowledging there’s not a great alternative — have a range of motivations. Some are hoping to develop a novel treatment for cancer. Others want to create the next Botox. Most are looking for organisms with exceptional traits that might offer the missing piece in their new product. That is why patents are filled with“extremophiles,” known for doing well in extreme darkness, cold, acidity and other harsh environments, said Robert Blasiak, a researcher from the Stockholm Resilience Centre who was involved in the patent study. In 1933, with Hitler and the Nazis boycotting Jewish businesses, many powerful Jews in Germany and the powerful American Jewish charities opposed retaliation, advocating negotiation instead. Some viewed Hitler as a “weak man” and wanted to “strengthen his hand”: “Once the Nazis had cleansed Germany of opposition parties and ended parliamentary government, they turned their attention to the Jews. By mid-March, the rank-and-file were storming department stores and demanding a boycott of Jewish businesses. As much to guide as to incite these volatile emotions. Hitler and Goebbels championed the idea of a boycott. In a March 27 radio broadcast, the government announced that on the morning of April 1st, at the stroke of ten, SA and SS members would take up positions outside Jewish stores and warn the public not to enter. This offense was portrayed as a defensive measure against ‘Jewish atrocity propaganda abroad.’ To add further terror, Göring told Jewish community leaders that they would be held responsible for any anti-German propaganda appearing abroad. Eager to create jobs through exports, Hitler wanted to minimize adverse publicity overseas.

In 1933, with Hitler and the Nazis boycotting Jewish businesses, many powerful Jews in Germany and the powerful American Jewish charities opposed retaliation, advocating negotiation instead. Some viewed Hitler as a “weak man” and wanted to “strengthen his hand”: “Once the Nazis had cleansed Germany of opposition parties and ended parliamentary government, they turned their attention to the Jews. By mid-March, the rank-and-file were storming department stores and demanding a boycott of Jewish businesses. As much to guide as to incite these volatile emotions. Hitler and Goebbels championed the idea of a boycott. In a March 27 radio broadcast, the government announced that on the morning of April 1st, at the stroke of ten, SA and SS members would take up positions outside Jewish stores and warn the public not to enter. This offense was portrayed as a defensive measure against ‘Jewish atrocity propaganda abroad.’ To add further terror, Göring told Jewish community leaders that they would be held responsible for any anti-German propaganda appearing abroad. Eager to create jobs through exports, Hitler wanted to minimize adverse publicity overseas. He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth. I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

When it comes to evil, nobody beats Hitler. He committed the biggest mass murder of innocent humans in all of history.

When it comes to evil, nobody beats Hitler. He committed the biggest mass murder of innocent humans in all of history.