Neil Gross in the New York Times:

There is a longstanding debate among social scientists about what ultimately drives human behavior. Do ideals, symbols and beliefs lead people to act as they do? Or are the wellsprings of action and the drivers of history less ethereal: money, fear, the thirst for power, circumstance and opportunity, with culture as an afterthought?

There is a longstanding debate among social scientists about what ultimately drives human behavior. Do ideals, symbols and beliefs lead people to act as they do? Or are the wellsprings of action and the drivers of history less ethereal: money, fear, the thirst for power, circumstance and opportunity, with culture as an afterthought?

Scholars in the first camp are culturalists; in the second, materialists. And the disagreement between them is not merely academic. It spills over into heated policy debates about crime, poverty, immigration, economic development and everything in between.

In “Rule Makers, Rule Breakers,” the psychologist Michele Gelfand sides with the culturalists. “Culture is a stubborn mystery of our experience and one of the last uncharted frontiers,” she writes. Her aim isn’t to guide readers through all the complex elements that make up a culture, but to draw attention to one aspect she believes has been ignored: the social norms — or the often informal rules of conduct, the dos and don’ts, the sources of tsking and raised eyebrows — that emerge whenever people band together.

More here.

About 40 years ago, Americans started getting much larger. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 80 percent of

About 40 years ago, Americans started getting much larger. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 80 percent of  As I write these words, I await Israel’s destruction of the only home and community that I have known in my 52 years of life. The 180 residents of my West Bank village,

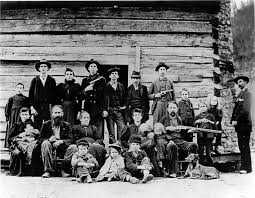

As I write these words, I await Israel’s destruction of the only home and community that I have known in my 52 years of life. The 180 residents of my West Bank village,  The so-called Hog Trial took place against a background of bitterness regarding Cline-McCoy loss of land in West Virginia. It’s hard not to recognize the hardships of the postwar decades in the mountains, particularly for the less affluent McCoys, for whom the butchering of a hog could mean the difference between eating or going hungry for some weeks. Fencing the steep land wasn’t practical, and livestock wandered between homesteads; farmers notched the ears of their animals as a form of branding. McCoy saw his notch on Floyd Hatfield’s hog and filed suit. Floyd, Anse’s cousin, lived on the Kentucky side of the river and was related to both families. Some say Randall McCoy’s actual motivation was anger that Floyd worked for Anse’s profitable timber operation. The local justice of the peace, “Preacher Anse” Hatfield, cousin to Devil Anse, impaneled a jury that was half Hatfield men, half McCoy men. McCoy juror Selkirk McCoy—son of Asa Harmon McCoy, the Union soldier murdered thirteen years before—worked, with two of his sons, among the thirty-five to forty men on the Hatfield timber crew. He apparently valued the present more than the past, and voted against Randall McCoy. No violence ensued, but the “betrayal” fueled resentment among the families. McCoy, a subsistence farmer and sometime ferryboat operator, was unable to provide economic stability or social or political status for his clan, while Hatfield’s success protected his family and employees from the economic decline endemic to the Tug Valley. The McCoy family was understandably frustrated, even furious, at the seemingly undefeated Hatfields.

The so-called Hog Trial took place against a background of bitterness regarding Cline-McCoy loss of land in West Virginia. It’s hard not to recognize the hardships of the postwar decades in the mountains, particularly for the less affluent McCoys, for whom the butchering of a hog could mean the difference between eating or going hungry for some weeks. Fencing the steep land wasn’t practical, and livestock wandered between homesteads; farmers notched the ears of their animals as a form of branding. McCoy saw his notch on Floyd Hatfield’s hog and filed suit. Floyd, Anse’s cousin, lived on the Kentucky side of the river and was related to both families. Some say Randall McCoy’s actual motivation was anger that Floyd worked for Anse’s profitable timber operation. The local justice of the peace, “Preacher Anse” Hatfield, cousin to Devil Anse, impaneled a jury that was half Hatfield men, half McCoy men. McCoy juror Selkirk McCoy—son of Asa Harmon McCoy, the Union soldier murdered thirteen years before—worked, with two of his sons, among the thirty-five to forty men on the Hatfield timber crew. He apparently valued the present more than the past, and voted against Randall McCoy. No violence ensued, but the “betrayal” fueled resentment among the families. McCoy, a subsistence farmer and sometime ferryboat operator, was unable to provide economic stability or social or political status for his clan, while Hatfield’s success protected his family and employees from the economic decline endemic to the Tug Valley. The McCoy family was understandably frustrated, even furious, at the seemingly undefeated Hatfields. In the conduct of public affairs in the 1530s, Cromwell seems ubiquitous and MacCulloch does more than any previous scholar (or even previous scholarship in aggregate) to track the range of his activities. There is a fascinating retelling of a familiar story: his role in dissolving monasteries. Cromwell was not, MacCulloch argues, ideologically wedded to complete appropriation of monastic assets; the Court of Augmentations – set up to handle the windfall, and the centrepiece of Elton’s ‘Tudor revolution’ – turns out not to have been his idea. Cromwell was, however, deeply concerned with the regulation of weirs and waterworks, a subject of possibly greater concern to some of the gentry. We learn of Cromwell’s adeptness in managing the governance of Wales, his much less sure hand (with future consequences) in attempting the same for Ireland and an apparent lack of interest in the affairs of Scotland. Another blind spot was the north of England, where Cromwell lacked connections and clientage: he was the target of vicious antipathy during the 1536–7 Pilgrimage of Grace.

In the conduct of public affairs in the 1530s, Cromwell seems ubiquitous and MacCulloch does more than any previous scholar (or even previous scholarship in aggregate) to track the range of his activities. There is a fascinating retelling of a familiar story: his role in dissolving monasteries. Cromwell was not, MacCulloch argues, ideologically wedded to complete appropriation of monastic assets; the Court of Augmentations – set up to handle the windfall, and the centrepiece of Elton’s ‘Tudor revolution’ – turns out not to have been his idea. Cromwell was, however, deeply concerned with the regulation of weirs and waterworks, a subject of possibly greater concern to some of the gentry. We learn of Cromwell’s adeptness in managing the governance of Wales, his much less sure hand (with future consequences) in attempting the same for Ireland and an apparent lack of interest in the affairs of Scotland. Another blind spot was the north of England, where Cromwell lacked connections and clientage: he was the target of vicious antipathy during the 1536–7 Pilgrimage of Grace. The emphasis on situation is one of the key factors that distinguishes Beauvoir from other existentialists. For Beauvoir, we are free, but we are also thrown into contexts where we don’t always have the freedom to choose. This is very different from Jean-Paul Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom; by his lights, any attempt to blame our situation for our predicament is a denial of freedom – a form of bad faith. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre imagined an impassable crag – a “brute existent”, to use a Heideggerian term – and suggested that it’s only impassable if one had imagined that it would be possible to climb it. In a not-so-subtle attack on this idea, Beauvoir argues in Ethics of Ambiguity that, “If a door refuses to open, let us accept not opening it and there we are free. But by doing that, one manages only to save an abstract notion of freedom. It is emptied of all content and all truth”. Whereas for Sartre, “success is not important to freedom”, Beauvoir’s point is that without the possibility to act – if we’re limited by our situation – then freedom is rendered impotent. We may be free to scale a crag, but unless we have the power to do it, it means nothing.

The emphasis on situation is one of the key factors that distinguishes Beauvoir from other existentialists. For Beauvoir, we are free, but we are also thrown into contexts where we don’t always have the freedom to choose. This is very different from Jean-Paul Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom; by his lights, any attempt to blame our situation for our predicament is a denial of freedom – a form of bad faith. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre imagined an impassable crag – a “brute existent”, to use a Heideggerian term – and suggested that it’s only impassable if one had imagined that it would be possible to climb it. In a not-so-subtle attack on this idea, Beauvoir argues in Ethics of Ambiguity that, “If a door refuses to open, let us accept not opening it and there we are free. But by doing that, one manages only to save an abstract notion of freedom. It is emptied of all content and all truth”. Whereas for Sartre, “success is not important to freedom”, Beauvoir’s point is that without the possibility to act – if we’re limited by our situation – then freedom is rendered impotent. We may be free to scale a crag, but unless we have the power to do it, it means nothing. Until recent years, the sound of rain has always filled me with a sense of blessing. Rain drumming on the tin roof of a Tennessee farmhouse, my first home. Rain pattering on the canopy of oak and maple forests in Ohio, on forests of pine in Maine and Vermont, on reeds and rushes in Louisiana bayous, on spongy nurse logs in Oregon, on tundra and stone in Alaska. From earliest childhood, I would tingle with anticipation at the rumble of an oncoming storm. I would shiver with pleasure as rain tapped on windows and gurgled through gutters, and I would dash outside to rejoice in the thrum of rain on my umbrella or on the hood of my slicker. I heard in these sounds a promise of green grass, sweet corn, flowing creeks. It was the music of abundance. When preachers in the rural Methodist churches I attended as a boy spoke of grace, I thought of rain.

Until recent years, the sound of rain has always filled me with a sense of blessing. Rain drumming on the tin roof of a Tennessee farmhouse, my first home. Rain pattering on the canopy of oak and maple forests in Ohio, on forests of pine in Maine and Vermont, on reeds and rushes in Louisiana bayous, on spongy nurse logs in Oregon, on tundra and stone in Alaska. From earliest childhood, I would tingle with anticipation at the rumble of an oncoming storm. I would shiver with pleasure as rain tapped on windows and gurgled through gutters, and I would dash outside to rejoice in the thrum of rain on my umbrella or on the hood of my slicker. I heard in these sounds a promise of green grass, sweet corn, flowing creeks. It was the music of abundance. When preachers in the rural Methodist churches I attended as a boy spoke of grace, I thought of rain. The science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein once wrote, “Each generation thinks it invented sex.” He was presumably referring to the pride each generation takes in defining its own sexual practices and ethics. But his comment hit the mark in another sense: Every generation has to reinvent sex because the previous generation did a lousy job of teaching it. In the United States, the conversations we have with our children about sex are often awkward, limited, and brimming with euphemism. At school, if kids are lucky enough to live in a state that allows it, they’ll get something like 10 total hours of sex education.1 If they’re less lucky, they’ll instead experience the curious phenomenon of abstinence-only education, in which the goal is to avoid transmitting any information at all. In addition to being counterproductive—potentially leading to higher rates of teen pregnancy2 and sexually transmitted illnesses3—this practice is strange. Compare it to the practices of many small-scale societies, where children first learn about sex by observing their parents!

The science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein once wrote, “Each generation thinks it invented sex.” He was presumably referring to the pride each generation takes in defining its own sexual practices and ethics. But his comment hit the mark in another sense: Every generation has to reinvent sex because the previous generation did a lousy job of teaching it. In the United States, the conversations we have with our children about sex are often awkward, limited, and brimming with euphemism. At school, if kids are lucky enough to live in a state that allows it, they’ll get something like 10 total hours of sex education.1 If they’re less lucky, they’ll instead experience the curious phenomenon of abstinence-only education, in which the goal is to avoid transmitting any information at all. In addition to being counterproductive—potentially leading to higher rates of teen pregnancy2 and sexually transmitted illnesses3—this practice is strange. Compare it to the practices of many small-scale societies, where children first learn about sex by observing their parents! The dubious notion

The dubious notion The medical community has been aware of the placebo effect–the phenomenon in which a nontherapeutic treatment (like a sham pill) improves a patient’s physical condition–for centuries. But Ted Kaptchuk, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and one of the leading researchers on the placebo effect, wanted to take his research further. He was tired of letting the people in his studies think they were taking a real therapy and then watching what happened. Instead, he wondered, what if he was honest? His Harvard colleagues told Kaptchuk he was crazy, that letting people in a clinical trial know they were taking a placebo would defeat the purpose. Nevertheless, in 2009 the university’s teaching hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, launched the first open-label placebo, or so-called honest placebo, trial to date, starting with people who had IBS, including Buonanno.

The medical community has been aware of the placebo effect–the phenomenon in which a nontherapeutic treatment (like a sham pill) improves a patient’s physical condition–for centuries. But Ted Kaptchuk, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and one of the leading researchers on the placebo effect, wanted to take his research further. He was tired of letting the people in his studies think they were taking a real therapy and then watching what happened. Instead, he wondered, what if he was honest? His Harvard colleagues told Kaptchuk he was crazy, that letting people in a clinical trial know they were taking a placebo would defeat the purpose. Nevertheless, in 2009 the university’s teaching hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, launched the first open-label placebo, or so-called honest placebo, trial to date, starting with people who had IBS, including Buonanno. Ten years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the official economic statistics — the ones that fill news stories, television shows and presidential tweets — say that the American economy is fully recovered.

Ten years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the official economic statistics — the ones that fill news stories, television shows and presidential tweets — say that the American economy is fully recovered. I was born in 1955 and—apart from the Castilian (which you know as Spanish) spoken by a minority of speakers—Galician was the language spoken in Galicia. What can be done with a people of whom a majority speak an incorrect language? Francoism made the answer very clear; its policy of emigration/deportation was successful. Thousands of Galician speakers were proletarianized across a Europe in need of cheap labor after the Second World War. With its demographic policy of emigration, Franco’s government met several objectives. One of those was, precisely, to break the transmission of Galician from one generation to the next. I belong to an intermediate generation; my parents were native Galician speakers but always spoke to us in Castilian, as they didn’t want their children to have painful issues in adapting, as they’d had. Naturally, what my generation inherited from our parents was a linguistic conflict, of which I spoke in Secession. My native language is the fascist prohibition against speaking the language of my progenitors, of the women who preceded me. This is definitely the case.

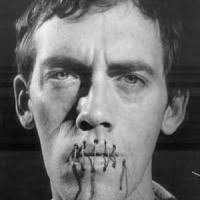

I was born in 1955 and—apart from the Castilian (which you know as Spanish) spoken by a minority of speakers—Galician was the language spoken in Galicia. What can be done with a people of whom a majority speak an incorrect language? Francoism made the answer very clear; its policy of emigration/deportation was successful. Thousands of Galician speakers were proletarianized across a Europe in need of cheap labor after the Second World War. With its demographic policy of emigration, Franco’s government met several objectives. One of those was, precisely, to break the transmission of Galician from one generation to the next. I belong to an intermediate generation; my parents were native Galician speakers but always spoke to us in Castilian, as they didn’t want their children to have painful issues in adapting, as they’d had. Naturally, what my generation inherited from our parents was a linguistic conflict, of which I spoke in Secession. My native language is the fascist prohibition against speaking the language of my progenitors, of the women who preceded me. This is definitely the case. Today, David Wojnarowicz is known mostly as a martyr to the culture wars of the 1980s, another artist diagnosed with AIDS who fought along with so many to get the government to act, for a long time in vain, and who then, like so many others, died of the disease, a terrible tear in the fabric of art that was savagely exacted on gay men of that generation. Wojnarowicz came out of the same deeply downtown bohemianism of the early 1980s that fueled Jean-Michel Basquiat’s equally short, culture-altering arc through the art world: small cadres of like-minded underground characters and self-defined artists, desperate to act on the culture but denied the usual access to artistic power structures for reasons financial, psychological, racial, sexual. Wojnarowicz rose amid a gritty East Village aesthetic of graffiti, Expressionistic gestures, roughly assembled surfaces, funky found objects, one-night shows at clubs, and midnight guerrilla actions on the finer art. But in a way, Wojnarowicz’s tremendous, almost Rimbaud-like reputation suits, since he was an even better, more lucid freedom fighter than he was an artist.

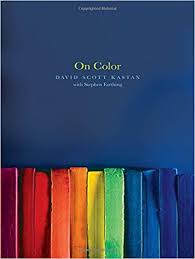

Today, David Wojnarowicz is known mostly as a martyr to the culture wars of the 1980s, another artist diagnosed with AIDS who fought along with so many to get the government to act, for a long time in vain, and who then, like so many others, died of the disease, a terrible tear in the fabric of art that was savagely exacted on gay men of that generation. Wojnarowicz came out of the same deeply downtown bohemianism of the early 1980s that fueled Jean-Michel Basquiat’s equally short, culture-altering arc through the art world: small cadres of like-minded underground characters and self-defined artists, desperate to act on the culture but denied the usual access to artistic power structures for reasons financial, psychological, racial, sexual. Wojnarowicz rose amid a gritty East Village aesthetic of graffiti, Expressionistic gestures, roughly assembled surfaces, funky found objects, one-night shows at clubs, and midnight guerrilla actions on the finer art. But in a way, Wojnarowicz’s tremendous, almost Rimbaud-like reputation suits, since he was an even better, more lucid freedom fighter than he was an artist. Yet perhaps one of the greatest compliments I can give “On Color” is that despite the indisputable scholarly erudition found on every page, the clever edge to its witty prose and its own defiantly unclassifiable

Yet perhaps one of the greatest compliments I can give “On Color” is that despite the indisputable scholarly erudition found on every page, the clever edge to its witty prose and its own defiantly unclassifiable  In the world’s most famous thought experiment, physicist Erwin Schrödinger described how a cat in a box could be in an uncertain predicament. The peculiar rules of quantum theory meant that it could be both dead and alive, until the box was opened and the cat’s state measured. Now, two physicists have devised a modern version of the paradox by replacing the cat with a physicist doing experiments—with shocking implications. Quantum theory has a long history of thought experiments, and in most cases these are used to point to weaknesses in various interpretations of quantum mechanics. But the latest version, which involves multiple players, is unusual: it shows that if the standard interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, then different experimenters can reach opposite conclusions about what the physicist in the box has measured. This means that quantum theory contradicts itself.

In the world’s most famous thought experiment, physicist Erwin Schrödinger described how a cat in a box could be in an uncertain predicament. The peculiar rules of quantum theory meant that it could be both dead and alive, until the box was opened and the cat’s state measured. Now, two physicists have devised a modern version of the paradox by replacing the cat with a physicist doing experiments—with shocking implications. Quantum theory has a long history of thought experiments, and in most cases these are used to point to weaknesses in various interpretations of quantum mechanics. But the latest version, which involves multiple players, is unusual: it shows that if the standard interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, then different experimenters can reach opposite conclusions about what the physicist in the box has measured. This means that quantum theory contradicts itself. This thought kept blinking through my mind, like a neon sign on a dark street, as I read These Truths, the newest book by Harvard professor and The New Yorker contributor Jill Lepore. A 900-plus page tome, it is a full history of the United States, a country I was born in and soon after left. I was raised in a much younger country, Israel, which was handed over by a colonizing force to a people desperate for a home, back in the days—not so long ago, really—when colonizers could simply gift the land they’d taken as if it were theirs to give. The history I was taught from the ages of six to eighteen was both condensed and elongated, the history of a fledgling country full of war but also of an ancient people once enslaved and long persecuted.

This thought kept blinking through my mind, like a neon sign on a dark street, as I read These Truths, the newest book by Harvard professor and The New Yorker contributor Jill Lepore. A 900-plus page tome, it is a full history of the United States, a country I was born in and soon after left. I was raised in a much younger country, Israel, which was handed over by a colonizing force to a people desperate for a home, back in the days—not so long ago, really—when colonizers could simply gift the land they’d taken as if it were theirs to give. The history I was taught from the ages of six to eighteen was both condensed and elongated, the history of a fledgling country full of war but also of an ancient people once enslaved and long persecuted.