Helen Macdonald in The Atlantic:

I can make a passable imitation of a raven’s low, guttural croak, and whenever I see a wild one flying overhead I have an irresistible urge to call up to it in the hope that it will answer back. Sometimes I do, and sometimes it does; it’s a moment of cross-species communication that never fails to thrill. Ravens are strangely magical birds. Partly that magic is made by us. They have been seen variously as gods, tricksters, protectors, messengers, and harbingers of death for thousands of years. But much of that magic emanates from the living birds themselves. Massive black corvids with ice-pick beaks, dark eyes, and shaggy-feathered necks, they have a distinctive presence and possess a fierce intelligence. Watching them for any length of time has the same effect as watching great apes: It’s hard not to start thinking of them as people. Nonhuman people, but people all the same.

I can make a passable imitation of a raven’s low, guttural croak, and whenever I see a wild one flying overhead I have an irresistible urge to call up to it in the hope that it will answer back. Sometimes I do, and sometimes it does; it’s a moment of cross-species communication that never fails to thrill. Ravens are strangely magical birds. Partly that magic is made by us. They have been seen variously as gods, tricksters, protectors, messengers, and harbingers of death for thousands of years. But much of that magic emanates from the living birds themselves. Massive black corvids with ice-pick beaks, dark eyes, and shaggy-feathered necks, they have a distinctive presence and possess a fierce intelligence. Watching them for any length of time has the same effect as watching great apes: It’s hard not to start thinking of them as people. Nonhuman people, but people all the same.

The most celebrated ravens in the world live at the Tower of London, on the River Thames, an 11th-century walled enclosure of towers and buildings that houses the Crown Jewels and that over the ages has functioned as a royal palace, a zoo, a prison, and a place of execution. Today it is one of Britain’s most visited tourist attractions, and its ravens amble across its greens entirely unbothered by the crowds, walking with a gait that Charles Dickens—who kept ravens—described as resembling “a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles.”

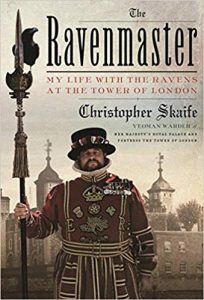

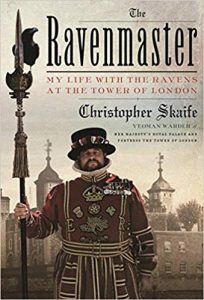

I met Christopher Skaife a few years ago while recording a radio program about Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” A jovial, bearded man, he’s one of the yeoman warders at the Tower of London. As such he is a member of an ancient and soldierly profession. For the past 13 years he has also been the site’s ravenmaster, which easily tops my list of favorite job titles (unicef’s “head of knowledge” comes in second). On Twitter, as @Ravenmaster1, he curates a much-loved feed packed with images of the birds in his care: raven beaks holding information leaflets, photos of the feathers on their broad backs, close-ups of their varied expressions, videos of their gentle interactions with him. A born storyteller with a gift for banter honed by years in the British army, Skaife has written a book that is far from a dry monograph about the species or a sentimental love letter to his birds.

I met Christopher Skaife a few years ago while recording a radio program about Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” A jovial, bearded man, he’s one of the yeoman warders at the Tower of London. As such he is a member of an ancient and soldierly profession. For the past 13 years he has also been the site’s ravenmaster, which easily tops my list of favorite job titles (unicef’s “head of knowledge” comes in second). On Twitter, as @Ravenmaster1, he curates a much-loved feed packed with images of the birds in his care: raven beaks holding information leaflets, photos of the feathers on their broad backs, close-ups of their varied expressions, videos of their gentle interactions with him. A born storyteller with a gift for banter honed by years in the British army, Skaife has written a book that is far from a dry monograph about the species or a sentimental love letter to his birds.

More here.

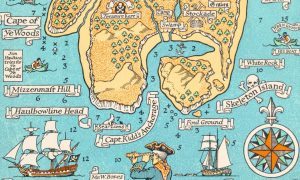

In the beginning was the map. Robert Louis Stevenson drew it in the summer of 1881 to entertain his 12-year-old stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, while on a rainy family holiday in Scotland. It depicts a rough-coasted island of woods, peaks, swamps and coves. A few place names are marked, which speak of adventure and disaster: Spyeglass Hill, Graves, Skeleton Island. The penmanship is deft, confident – at the island’s southern end is an intricate compass rose, and the sketch of a galleon at full sail. Figures signal the depth in fathoms of the surrounding sea, and there are warnings to mariners: “Strong tide here”, “Foul ground”. In the heart of the island is a blood-red cross, by which is scrawled the legend “Bulk of treasure here”.

In the beginning was the map. Robert Louis Stevenson drew it in the summer of 1881 to entertain his 12-year-old stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, while on a rainy family holiday in Scotland. It depicts a rough-coasted island of woods, peaks, swamps and coves. A few place names are marked, which speak of adventure and disaster: Spyeglass Hill, Graves, Skeleton Island. The penmanship is deft, confident – at the island’s southern end is an intricate compass rose, and the sketch of a galleon at full sail. Figures signal the depth in fathoms of the surrounding sea, and there are warnings to mariners: “Strong tide here”, “Foul ground”. In the heart of the island is a blood-red cross, by which is scrawled the legend “Bulk of treasure here”.

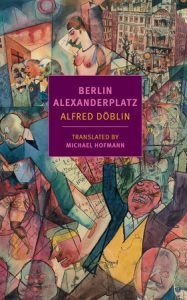

In the tempest-plagued teapot of English translation, Michael Hofmann’s dust-ups are notorious: he compared Stefan Zweig’s suicide note to an Oscar acceptance speech, eviscerated James Reidel’s translations of Thomas Bernhard’s poems, brushed off George Konrad’s A Feast in the Garden as “dire… export-quality horseshit.” Critics seem generally pleased with his translations, but then, critics like Toril Moi, Tim Parks, or Hofmann himself—that is to say, those willing and able to scrutinize the changes a text in translation undergoes, and the details of what is gained and lost alone the way—are rare, and the newspaper reviewer’s “cleverly translated,” “serviceably translated,” and suchlike don’t count for too much. Readers I know are not of one mind about his work: some are unqualified fans, particularly of Angina Days, his selected poetry of Günter Eich. What seems to grate on the less enthusiastic are his translations’ motley surfaces, the “occasional rhinestones or bits of jet,” as he has it in one interview, which mark them, not as the pellucid transmigration of the author’s inspiration from source language into target, but as a patent contrivance in the latter.

In the tempest-plagued teapot of English translation, Michael Hofmann’s dust-ups are notorious: he compared Stefan Zweig’s suicide note to an Oscar acceptance speech, eviscerated James Reidel’s translations of Thomas Bernhard’s poems, brushed off George Konrad’s A Feast in the Garden as “dire… export-quality horseshit.” Critics seem generally pleased with his translations, but then, critics like Toril Moi, Tim Parks, or Hofmann himself—that is to say, those willing and able to scrutinize the changes a text in translation undergoes, and the details of what is gained and lost alone the way—are rare, and the newspaper reviewer’s “cleverly translated,” “serviceably translated,” and suchlike don’t count for too much. Readers I know are not of one mind about his work: some are unqualified fans, particularly of Angina Days, his selected poetry of Günter Eich. What seems to grate on the less enthusiastic are his translations’ motley surfaces, the “occasional rhinestones or bits of jet,” as he has it in one interview, which mark them, not as the pellucid transmigration of the author’s inspiration from source language into target, but as a patent contrivance in the latter. “The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity,” writes Martin Amis in his memoir Experience. “Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending…”

“The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity,” writes Martin Amis in his memoir Experience. “Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending…”

I can make a

I can make a  I met

I met  Homi Bhabha:

Homi Bhabha:

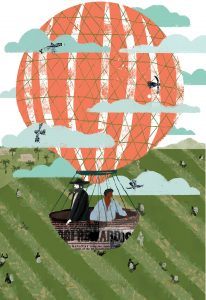

When the novel “Washington Black” opens, it is 1830 and the young George Washington Black, who narrates his own story, is a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation called Faith, protected, or at least watched over, by an older woman, Big Kit. As a new master takes charge, the fear is palpable. The accounts of murders and punishments and random cruelties are chilling and unsparing. Big Kit can see no way out except death: “Death was a door. I think that is what she wished me to understand. She did not fear it. She was of an ancient faith rooted in the high river lands of Africa, and in that faith the dead were reborn, whole, back in their homelands, to walk again free.” The reader can almost see what is coming. Since Barbados was under British rule, slavery was abolished there in 1834. This, then, could be a novel about the last days of the cruelty, about what happens to a slave-owning family and to the slaves during the waning of the old dispensation.

When the novel “Washington Black” opens, it is 1830 and the young George Washington Black, who narrates his own story, is a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation called Faith, protected, or at least watched over, by an older woman, Big Kit. As a new master takes charge, the fear is palpable. The accounts of murders and punishments and random cruelties are chilling and unsparing. Big Kit can see no way out except death: “Death was a door. I think that is what she wished me to understand. She did not fear it. She was of an ancient faith rooted in the high river lands of Africa, and in that faith the dead were reborn, whole, back in their homelands, to walk again free.” The reader can almost see what is coming. Since Barbados was under British rule, slavery was abolished there in 1834. This, then, could be a novel about the last days of the cruelty, about what happens to a slave-owning family and to the slaves during the waning of the old dispensation. Sally Horner was a widow’s daughter, a brown-haired honor student, from Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, hoping to impress some popular girls, she nicked a notebook from a dime store and was accosted by a man, Frank La Salle, posing as an F.B.I. agent. La Salle, who told Horner his name was Frank Warren, informed the eleven-year-old that he was placing her under surveillance. Then he commanded her to take a bus with him to Atlantic City, and from there they embarked on a cross-country road trip. Like Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of the novel “

Sally Horner was a widow’s daughter, a brown-haired honor student, from Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, hoping to impress some popular girls, she nicked a notebook from a dime store and was accosted by a man, Frank La Salle, posing as an F.B.I. agent. La Salle, who told Horner his name was Frank Warren, informed the eleven-year-old that he was placing her under surveillance. Then he commanded her to take a bus with him to Atlantic City, and from there they embarked on a cross-country road trip. Like Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of the novel “ In a report

In a report  It has been a year since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving a trail of destruction: ruined infrastructure, destroyed homes, and thousands of fatalities. Since that particular hurricane has largely faded from the news, the slow rebuild continues and defining questions loom over the process: Who is Puerto Rico for? Outside investors and tourists or Puerto Ricans? After a collective trauma like Hurricane Maria, who has the right to decide for Puerto Rico? The fight for its future is underway.

It has been a year since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving a trail of destruction: ruined infrastructure, destroyed homes, and thousands of fatalities. Since that particular hurricane has largely faded from the news, the slow rebuild continues and defining questions loom over the process: Who is Puerto Rico for? Outside investors and tourists or Puerto Ricans? After a collective trauma like Hurricane Maria, who has the right to decide for Puerto Rico? The fight for its future is underway. During the warm summer nights three years before Maidan, just as my Kyiv life began, I often stood where my grandma lived when her Kyiv life ended. Of all what drew to a close. Given everything that she told me, it seemed that those days were the happiest of her life: she was young and beautiful, she went on dates. ‘A few Jews were courting me’, she used to tell me proudly as if by way of feminine validation, as if to say, ‘Boy, I was hot!’ I’m not sure about the timeline. Maybe those happy years were directly after her father and brother came back from East Siberia in 1939; both had been arrested, tortured and imprisoned in a labour camp in 1937, but released two years later during the so called ‘Beria Amnesty’. She also witnessed the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932 and 1933, as well as the Babyn Yar massacre of 1941. I first learned of both tragedies from her, as they simply hadn’t featured in my Soviet school education. Those were the most terrifying years of Stalinist repression, yet she managed to find some joy in this city.

During the warm summer nights three years before Maidan, just as my Kyiv life began, I often stood where my grandma lived when her Kyiv life ended. Of all what drew to a close. Given everything that she told me, it seemed that those days were the happiest of her life: she was young and beautiful, she went on dates. ‘A few Jews were courting me’, she used to tell me proudly as if by way of feminine validation, as if to say, ‘Boy, I was hot!’ I’m not sure about the timeline. Maybe those happy years were directly after her father and brother came back from East Siberia in 1939; both had been arrested, tortured and imprisoned in a labour camp in 1937, but released two years later during the so called ‘Beria Amnesty’. She also witnessed the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932 and 1933, as well as the Babyn Yar massacre of 1941. I first learned of both tragedies from her, as they simply hadn’t featured in my Soviet school education. Those were the most terrifying years of Stalinist repression, yet she managed to find some joy in this city. Downes’s own meticulously descriptive pictures of the woebegone subjects that he favors—industrial zones, Texas deserts, highway structures, the New Jersey Meadowlands—do that, too, with a deadpan restraint that has kept his fan base small but ardent throughout the half century of his career. I’m a member. We cherish Downes’s evidence that painting can be truer than photography to the ways that our eyes process the world: reaping patches of tone and color which our brains combine very rapidly, but not instantly, into seamless wholes. He renders everything in his specialty of long, low panoramas, often encompassing more than a hundred and eighty degrees, which he always paints—on-site, over many sessions—head on, without either perspectival organization or fish-eye distortion. His avoidance of charm in his subjects and suppression of expressiveness in his touch serve the dumbfounded wonderment you can feel when—perhaps rarely enough, in this frantic era—you stop somewhere, look around, forget yourself, and only see. Downes’s is a puritanical passion, burning cold rather than hot but no less fiercely for that.

Downes’s own meticulously descriptive pictures of the woebegone subjects that he favors—industrial zones, Texas deserts, highway structures, the New Jersey Meadowlands—do that, too, with a deadpan restraint that has kept his fan base small but ardent throughout the half century of his career. I’m a member. We cherish Downes’s evidence that painting can be truer than photography to the ways that our eyes process the world: reaping patches of tone and color which our brains combine very rapidly, but not instantly, into seamless wholes. He renders everything in his specialty of long, low panoramas, often encompassing more than a hundred and eighty degrees, which he always paints—on-site, over many sessions—head on, without either perspectival organization or fish-eye distortion. His avoidance of charm in his subjects and suppression of expressiveness in his touch serve the dumbfounded wonderment you can feel when—perhaps rarely enough, in this frantic era—you stop somewhere, look around, forget yourself, and only see. Downes’s is a puritanical passion, burning cold rather than hot but no less fiercely for that. RAINDROP. IF THE MARK

RAINDROP. IF THE MARK Given the billions of dollars the world invests in science each year, it’s surprising how few researchers study science itself. But their number is growing rapidly, driven in part by the realization that science isn’t always the rigorous, objective search for knowledge it is supposed to be. Editors of medical journals, embarrassed by the quality of the papers they were publishing, began to turn the lens of science on their own profession decades ago, creating a new field now called “journalology.” More recently, psychologists have taken the lead, plagued by existential doubts after many results proved irreproducible. Other fields are following suit, and metaresearch, or research on research, is now blossoming as a scientific field of its own.

Given the billions of dollars the world invests in science each year, it’s surprising how few researchers study science itself. But their number is growing rapidly, driven in part by the realization that science isn’t always the rigorous, objective search for knowledge it is supposed to be. Editors of medical journals, embarrassed by the quality of the papers they were publishing, began to turn the lens of science on their own profession decades ago, creating a new field now called “journalology.” More recently, psychologists have taken the lead, plagued by existential doubts after many results proved irreproducible. Other fields are following suit, and metaresearch, or research on research, is now blossoming as a scientific field of its own.