Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

The first test of a new gene-editing tool in people has yielded early clues that the strategy—an infusion that turns the liver into an enzyme factory—could help treat a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Today, the biotech company Sangamo Therapeutics in Richmond, California, reported data suggesting that two patients with Hunter syndrome are now making small amounts of a crucial enzyme that their bodies previously could not produce. But the company is still a long way from providing evidence that the new method can improve Hunter patients’ health. Hunter syndrome results from a mutation in a gene for an enzyme that cells need to break down certain sugars. When these sugars, called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), build up in tissues, they damage organs such as the heart and lungs, sometimes leading to developmental delays, brain damage, and early death. The new treatment uses a gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs were developed earlier than CRISPR, the hugely popular gene-editing tool, and Sangamo has already used them to edit cells in a dish that were then returned to a patient’s body.

The first test of a new gene-editing tool in people has yielded early clues that the strategy—an infusion that turns the liver into an enzyme factory—could help treat a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Today, the biotech company Sangamo Therapeutics in Richmond, California, reported data suggesting that two patients with Hunter syndrome are now making small amounts of a crucial enzyme that their bodies previously could not produce. But the company is still a long way from providing evidence that the new method can improve Hunter patients’ health. Hunter syndrome results from a mutation in a gene for an enzyme that cells need to break down certain sugars. When these sugars, called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), build up in tissues, they damage organs such as the heart and lungs, sometimes leading to developmental delays, brain damage, and early death. The new treatment uses a gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs were developed earlier than CRISPR, the hugely popular gene-editing tool, and Sangamo has already used them to edit cells in a dish that were then returned to a patient’s body.

Sangamo’s new results are for four men with a mild form of Hunter disease. The participants were already receiving a standard Hunter syndrome therapy: weekly injections of iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS), the enzyme they lack. However, blood levels drop within a day of injections, limiting their effectiveness. To test the ZFNs, Sangamo injected patients with harmless viruses that ferry DNA for the nucleases into their liver cells, along with a good copy of the IDS gene. The ZFNs snip DNA in a specific location, which the cells then repair using the provided IDS gene. The landing spot is within the gene for the protein albumin, which has a strong on–off switch that controls the new IDS gene. Because of this powerful promotor, less than 1% of a person’s liver cells may produce sufficient amounts of IDS to treat Hunter disorder, says Sangamo President and CEO Sandy Macrae. Last November, Sangamo treated the first patient in its trial, Brian Madeux. Today, geneticist Joseph Muenzer of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, principal investigator for the trial, reported results for Madeux and three more patients at a meeting in Athens, Greece.

More here.

In the spring of 1815, already beset by poor health, Percy Shelley was tormented by a spell of coughing so vicious, and a pain in his side so intense, that he became convinced he was about to die. “An eminent physician,” wrote Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), diagnosed the malady as consumption, and so, throughout the spring and well into the summer, the poet was obsessed with thoughts of his mortality. He began imagining what might become of Mary were he indeed to perish. Not until early September did Shelley recover, yet his general gloom lingered; after all, there had been a death earlier that year—that of the couple’s first child. Having moved with Mary into a cottage on the border of Berkshire and Surrey, a hundred yards or so from the Great Park at Windsor, Shelley wrote the death-inflected “Alastor; or The Spirit of Solitude” and a work that more directly addressed his anxieties about his future wife: a Gothic, angst-ridden poem called “The Sunset.”

In the spring of 1815, already beset by poor health, Percy Shelley was tormented by a spell of coughing so vicious, and a pain in his side so intense, that he became convinced he was about to die. “An eminent physician,” wrote Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), diagnosed the malady as consumption, and so, throughout the spring and well into the summer, the poet was obsessed with thoughts of his mortality. He began imagining what might become of Mary were he indeed to perish. Not until early September did Shelley recover, yet his general gloom lingered; after all, there had been a death earlier that year—that of the couple’s first child. Having moved with Mary into a cottage on the border of Berkshire and Surrey, a hundred yards or so from the Great Park at Windsor, Shelley wrote the death-inflected “Alastor; or The Spirit of Solitude” and a work that more directly addressed his anxieties about his future wife: a Gothic, angst-ridden poem called “The Sunset.”

Jahangir’s course is directed by a woeman and is now, as it were, shut up by her so that all justice or care of anything or publique affayres either sleeps or depends on her, who is most unaccesible than any goddesse or mistery of heathen impietye.” So wrote in 1617 the disgruntled Thomas Roe, then British ambassador to the Mughal court, of the influence of the emperor’s 20th wife, Nur Jahan. Men everywhere, it seems, were threatened by the rise and reign of women, their racism and misogyny tied together in knots.

Jahangir’s course is directed by a woeman and is now, as it were, shut up by her so that all justice or care of anything or publique affayres either sleeps or depends on her, who is most unaccesible than any goddesse or mistery of heathen impietye.” So wrote in 1617 the disgruntled Thomas Roe, then British ambassador to the Mughal court, of the influence of the emperor’s 20th wife, Nur Jahan. Men everywhere, it seems, were threatened by the rise and reign of women, their racism and misogyny tied together in knots. The first test of a new gene-editing tool in people has yielded early clues that the strategy—an infusion that turns the liver into an enzyme factory—could help treat a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Today, the biotech company Sangamo Therapeutics in Richmond, California, reported data suggesting that two patients with Hunter syndrome are now making small amounts of a crucial enzyme that their bodies previously could not produce. But the company is still a long way from providing evidence that the new method can improve Hunter patients’ health. Hunter syndrome results from a mutation in a gene for an enzyme that cells need to break down certain sugars. When these sugars, called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), build up in tissues, they damage organs such as the heart and lungs, sometimes leading to developmental delays, brain damage, and early death. The new treatment uses a gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs were developed earlier than CRISPR, the hugely popular gene-editing tool, and Sangamo has already used them to edit cells in a dish that were then

The first test of a new gene-editing tool in people has yielded early clues that the strategy—an infusion that turns the liver into an enzyme factory—could help treat a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Today, the biotech company Sangamo Therapeutics in Richmond, California, reported data suggesting that two patients with Hunter syndrome are now making small amounts of a crucial enzyme that their bodies previously could not produce. But the company is still a long way from providing evidence that the new method can improve Hunter patients’ health. Hunter syndrome results from a mutation in a gene for an enzyme that cells need to break down certain sugars. When these sugars, called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), build up in tissues, they damage organs such as the heart and lungs, sometimes leading to developmental delays, brain damage, and early death. The new treatment uses a gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs were developed earlier than CRISPR, the hugely popular gene-editing tool, and Sangamo has already used them to edit cells in a dish that were then  On Sunday 28 April 1996, Martin Bryant was awoken by his alarm at 6am. He said goodbye to his girlfriend as she left the house, ate some breakfast, and set the burglar alarm before leaving his Hobart residence, as usual. He stopped briefly to purchase a coffee in the small town of Forcett, where he asked the cashier to “boil the kettle less time.” He then drove to the nearby town of Port Arthur, originally a colonial-era convict settlement populated only by a few hundred people. It was here that Bryant would go on to use the two rifles and a shotgun stashed inside a sports bag on the passenger seat of his car to perpetrate the worst massacre in modern Australian history. By the time it was over, 35 people were dead and a further 23 were left wounded.

On Sunday 28 April 1996, Martin Bryant was awoken by his alarm at 6am. He said goodbye to his girlfriend as she left the house, ate some breakfast, and set the burglar alarm before leaving his Hobart residence, as usual. He stopped briefly to purchase a coffee in the small town of Forcett, where he asked the cashier to “boil the kettle less time.” He then drove to the nearby town of Port Arthur, originally a colonial-era convict settlement populated only by a few hundred people. It was here that Bryant would go on to use the two rifles and a shotgun stashed inside a sports bag on the passenger seat of his car to perpetrate the worst massacre in modern Australian history. By the time it was over, 35 people were dead and a further 23 were left wounded. Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray is an unusual book, at once intensely personal and intellectually hard-edged. Although I disagree with it on many points, I recommend the book both as a well-written, moving intellectual autobiography and as an excellent exposition of some frontiers of foundational theoretical physics, largely told through dialogs with leading figures in the field.

Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray is an unusual book, at once intensely personal and intellectually hard-edged. Although I disagree with it on many points, I recommend the book both as a well-written, moving intellectual autobiography and as an excellent exposition of some frontiers of foundational theoretical physics, largely told through dialogs with leading figures in the field. Francis Fukuyama is tired of talking about the end of history. Thirty years ago, he published a wonky

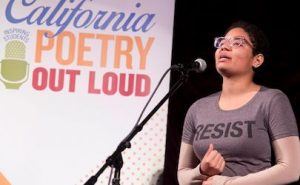

Francis Fukuyama is tired of talking about the end of history. Thirty years ago, he published a wonky  AMERICAN POETRY IS thriving. American poetry is in decline. The poetry audience has never been bigger. The audience has dropped to historic lows. The mass media ignores poetry. The media has rediscovered it. There have never been so many opportunities for poets. American poets find fewer options each year. The university provides a vibrant environment for poets. Academic culture has become stagnant and remote. Literary bohemias have been destroyed by gentrification and rising real estate prices. New bohemias have emerged across the nation. All of these contradictory statements are true, and all of them are false, depending on your point of view. The state of American poetry is a tale of two cities.

AMERICAN POETRY IS thriving. American poetry is in decline. The poetry audience has never been bigger. The audience has dropped to historic lows. The mass media ignores poetry. The media has rediscovered it. There have never been so many opportunities for poets. American poets find fewer options each year. The university provides a vibrant environment for poets. Academic culture has become stagnant and remote. Literary bohemias have been destroyed by gentrification and rising real estate prices. New bohemias have emerged across the nation. All of these contradictory statements are true, and all of them are false, depending on your point of view. The state of American poetry is a tale of two cities. Why, then, should we take a new look at Fabro? In my opinion, it is because of what he can tell us about the possibilities of sculpture.

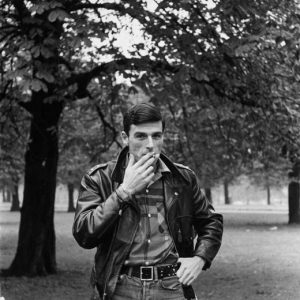

Why, then, should we take a new look at Fabro? In my opinion, it is because of what he can tell us about the possibilities of sculpture. The accepted view of Gunn, as Kleinzahler sums it up, was that in 1954 he ‘had removed himself to California where he would, as was alleged over and over, begin his long decline, undone by sunshine, LSD, queer sex and free verse’. Kleinzahler sought to challenge this idea of the softening of Gunn’s brain in California. ‘The city,’ he wrote, ‘will become his central theme, character and event being played out on its street corners, in its rooms, bars, bathhouses, stairwells, taxis.’ Kleinzahler also notes that, even when the poems became more relaxed and contemporary, ‘the “I” of the poetry’ carried ‘almost no tangible personality. This can be upsetting or disappointing to the contemporary reader, especially the American reader, accustomed to the dramatic personalities behind the voices in recent poetry: Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, Ginsberg, Plath, Hughes, et al. Even in Larkin there exists a strong, identifiable persona, no matter how recessive the tone.’

The accepted view of Gunn, as Kleinzahler sums it up, was that in 1954 he ‘had removed himself to California where he would, as was alleged over and over, begin his long decline, undone by sunshine, LSD, queer sex and free verse’. Kleinzahler sought to challenge this idea of the softening of Gunn’s brain in California. ‘The city,’ he wrote, ‘will become his central theme, character and event being played out on its street corners, in its rooms, bars, bathhouses, stairwells, taxis.’ Kleinzahler also notes that, even when the poems became more relaxed and contemporary, ‘the “I” of the poetry’ carried ‘almost no tangible personality. This can be upsetting or disappointing to the contemporary reader, especially the American reader, accustomed to the dramatic personalities behind the voices in recent poetry: Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, Ginsberg, Plath, Hughes, et al. Even in Larkin there exists a strong, identifiable persona, no matter how recessive the tone.’ In the middle of the day on 11 April 2014, a hooded gunman ambushed Gakirah Barnes on the streets of Chicago’s South Side. A volley of bullets struck her in the chest, jaw and neck. The 17-year-old died in a hospital bed two hours later. To many, her death was just another grim statistic from a city that has been struggling with gun violence. Last year, around 3,500 people were shot in Chicago, Illinois, of which 246 were aged 16 or younger; 38 of those children never celebrated another birthday. But Barnes’s death was unusual for several reasons. She was a young woman in an epidemic of violence that largely affects black men. She also had an Internet following. Barnes had a reputation as a ‘hitta’ — or killer — with rumours of at least two dead bodies to her credit. Although never charged with murder, she embraced the persona, posing in photos and videos with guns in her hands and making threats against rival gangs on Twitter. In a morbid modern irony, it’s likely that she revealed her location in real time to her killer through a tweet. Police have yet to charge anyone in connection with her murder.

In the middle of the day on 11 April 2014, a hooded gunman ambushed Gakirah Barnes on the streets of Chicago’s South Side. A volley of bullets struck her in the chest, jaw and neck. The 17-year-old died in a hospital bed two hours later. To many, her death was just another grim statistic from a city that has been struggling with gun violence. Last year, around 3,500 people were shot in Chicago, Illinois, of which 246 were aged 16 or younger; 38 of those children never celebrated another birthday. But Barnes’s death was unusual for several reasons. She was a young woman in an epidemic of violence that largely affects black men. She also had an Internet following. Barnes had a reputation as a ‘hitta’ — or killer — with rumours of at least two dead bodies to her credit. Although never charged with murder, she embraced the persona, posing in photos and videos with guns in her hands and making threats against rival gangs on Twitter. In a morbid modern irony, it’s likely that she revealed her location in real time to her killer through a tweet. Police have yet to charge anyone in connection with her murder. What are the limits of freedom of speech? It is a pressing question at a moment when conspiracy theories help to fuel fascist politics around the world. Shouldn’t liberal democracy promote a full airing of all possibilities, even false and bizarre ones, because the truth will eventually prevail?

What are the limits of freedom of speech? It is a pressing question at a moment when conspiracy theories help to fuel fascist politics around the world. Shouldn’t liberal democracy promote a full airing of all possibilities, even false and bizarre ones, because the truth will eventually prevail? Jazz occupies a special place in the American cultural landscape. It’s played in elegant concert halls and run-down bars, and can feature esoteric harmonic experimentation or good old-fashioned foot-stomping swing. Nobody embodies the scope of modern jazz better than Wynton Marsalis. As a trumpet player, bandleader, composer, educator, and ambassador for the music, he has worked tirelessly to keep jazz vibrant and alive. In this bouncy conversation, we talk about various kinds of music, how they might relate to physics, and some of the greater challenges facing the United States today.

Jazz occupies a special place in the American cultural landscape. It’s played in elegant concert halls and run-down bars, and can feature esoteric harmonic experimentation or good old-fashioned foot-stomping swing. Nobody embodies the scope of modern jazz better than Wynton Marsalis. As a trumpet player, bandleader, composer, educator, and ambassador for the music, he has worked tirelessly to keep jazz vibrant and alive. In this bouncy conversation, we talk about various kinds of music, how they might relate to physics, and some of the greater challenges facing the United States today. When people ask about my religion I usually just say I’m an atheist and I have no religion. If they continue, I usually give them what they want, and state my parents are Muslim, or I am from a Muslim background (most of the time the people asking for what it’s worth are themselves Muslims, or from a Muslim background, or, not American). I never say that I used to be a Muslim because that’s really not true.

When people ask about my religion I usually just say I’m an atheist and I have no religion. If they continue, I usually give them what they want, and state my parents are Muslim, or I am from a Muslim background (most of the time the people asking for what it’s worth are themselves Muslims, or from a Muslim background, or, not American). I never say that I used to be a Muslim because that’s really not true. Book Six brings My Struggle, after 3,600 pages, to an end. And so it has been subtitled, ominously—“The End.” Here, the writer who writes (and writes) about himself must write about that experience, too, and we duly find out what dinner-table conversation was like at the home of that very determined Norwegian who, between 2007 and 2011, got up at 4:30 am every weekday, sat down to his desktop computer in Malmö, Sweden, and for a few hours did his best to mention in print all that was unmentionable about his life, stopping only when his three small children woke up and demanded he make them breakfast. Book Six tells this story: the struggle behind the Struggle. No one will be shocked to discover that all the prizes and praise have only brought Karl Ove more pain. There’s also the small problem of having linked his name for all time with you-know-who. “Turns out he’s read Mein Kampf,” as his then-wife, Linda Boström, tells him of a new friend. “Hitler’s, that is.” She met her friend at the Malmö mental hospital. She went there voluntarily not long after reading Book Two, among whose radical aesthetic moves was a scene recalling the time Karl Ove got drunk and tried to cheat on her. “It’s always struck me that I was a sailor’s wife,” she tells him. “But now it’s the other way around. Now I’m the sailor.”

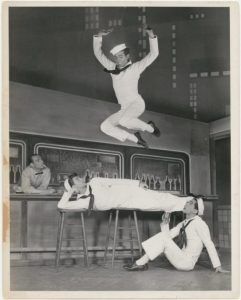

Book Six brings My Struggle, after 3,600 pages, to an end. And so it has been subtitled, ominously—“The End.” Here, the writer who writes (and writes) about himself must write about that experience, too, and we duly find out what dinner-table conversation was like at the home of that very determined Norwegian who, between 2007 and 2011, got up at 4:30 am every weekday, sat down to his desktop computer in Malmö, Sweden, and for a few hours did his best to mention in print all that was unmentionable about his life, stopping only when his three small children woke up and demanded he make them breakfast. Book Six tells this story: the struggle behind the Struggle. No one will be shocked to discover that all the prizes and praise have only brought Karl Ove more pain. There’s also the small problem of having linked his name for all time with you-know-who. “Turns out he’s read Mein Kampf,” as his then-wife, Linda Boström, tells him of a new friend. “Hitler’s, that is.” She met her friend at the Malmö mental hospital. She went there voluntarily not long after reading Book Two, among whose radical aesthetic moves was a scene recalling the time Karl Ove got drunk and tried to cheat on her. “It’s always struck me that I was a sailor’s wife,” she tells him. “But now it’s the other way around. Now I’m the sailor.” At the tender age of 25, Robbins made his first splash as a choreographer with a story ballet about three sailors on shore leave. The thirst for beer, adventure, and women brings out the primal urges of youth. Aptly titled

At the tender age of 25, Robbins made his first splash as a choreographer with a story ballet about three sailors on shore leave. The thirst for beer, adventure, and women brings out the primal urges of youth. Aptly titled