by Bill Murray

It all started with zebras.

Hard to believe, but sustained, hands-on field work in east Africa only has a sixty year history. Today Hans Klingel is an emeritus professor at the Braunschweig Zoological Institute, but when he arrived in Africa in 1962 Herr Klingel was one of only three scientists in the entire Serengeti.

Klingel and his wife made wildlife their career. Their first mission was to recognize individually and study ten percent of the 5500 zebras in the Ngorongoro Crater west of Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Zebra stripes are whole body fingerprints. The Klingels took photographs, taped the photos to file cards and carried them into the field. They came to recognize some 600 individuals.

Their file card technique caught on. In 1965 zoologist Bristol Foster studied giraffes at Nairobi National Park, photographing their left sides to memorize their unique patterns. He glued pictures onto file cards too. From 1969 a researcher named Carlos Mejia photographed and carried cards of giraffes in the Serengeti. Scientists swarmed into east Africa and the game was on.

On the open savanna, giraffes and zebras form a natural alliance. Zebras (and wildebeests, their fellow travelers) benefit from giraffes’ strong eyesight, elevated vantage point and superior field of view. Giraffes have the largest eyes among land animals and can see in color. Their peripheral vision allows them to just about see behind themselves. The next time your safari Land Cruiser rattles around the corner into view of a giraffe, you can bet the giraffe has already seen you.

In turn, giraffes appreciate zebras’ superior hearing and their awareness of the smell of predators. Perhaps because of their distance from the thick soup of ground smells, giraffes’ olfactory senses have fallen away.

A safari guide in Botswana’s Okavango Delta once described to me the most dramatic single wildlife event he ever saw; a fierce squall of giraffe anger led a long-necked posse to kill around ten lions before one giraffe finally went down to the final five.

If a horse’s kick can seriously injure a man, he explained, imagine the giraffe, whose foot is wide as a dinner plate. Having perfectly good sense, lions usually give giraffes wide berth. Except at the water hole.

Watch giraffes before they drink. They survey their surroundings at length and in great detail before they commit, for they will require time and effort to splay into the ungainly, legs-spread stance they need to get their mouths to the ground, and then more time to clamber back upright. Fortunately they needn’t drink more than every second or third day, because to counter the peril at the water hole, giraffes have learned which leaves yield the most moisture.

Nobody else except the largest elephant can reach twenty feet into the trees. There isn’t a great deal of feeding competition up there, so serene, heads in the clouds, giraffes can be discerning eaters.

If you weigh a ton and a half, you’ll need to eat a lot of leaves. You may spend three quarters of the day feeding. In Portraits in the Wild, Cynthia Moss writes that no more than five to thirty minutes of a giraffe’s day are spent sleeping.

Using your prehensile lips and half-meter prehensile, muscular tongue, you take a branch in your mouth, pull your head away and the leaves come with it. Your preferred leaves are thorny acacia, which contain some 74 per cent water. You grind the thorns between your molars.

Scientists like that word “prehensile” because it is obscure. It just means “adapted for holding,” from the Latin prehendere, “to grasp.” Unlike a giraffe’s hoof or a dog’s paw, our hands are prehensile, with our opposable thumbs.

•••••

At the border of the Luangwa Park in Zambia it is jarring to see people and giraffes sharing the road. The giraffes have eaten the leaves on the other side of the river inside the park, forming a browse line. The trees are bare of leaves below a line as distinct as the bottom of the clouds, while the other animals fight it out for food on the ground.

Giraffes aren’t out to hurt you, so workers, kids on their way to school, occasional automotive traffic and giraffes share the road, if gingerly. Most unusual.

You’ve seen squirrels, maybe rabbits, dart onto the road in front of you, become confused and run straight ahead instead of ducking off to the side. Once a giraffe did just that in front of our vehicle near a bush camp on the Luangwa River.

A laptop had disappeared from a rondavel in camp a few days before. We happened upon two boys in deep woods, a place they surely shouldn’t have been. Caught out, they dropped their backpack and crashed away into the bush. Inside the backpack, the laptop. In the ruckus a thoroughly alarmed giraffe stormed onto the road ahead of the LandCruiser.

If giraffes ran like most hoofstock their extra-long legs would get tangled up, so when they run they move both legs on one side and then the other. All four of a giraffe’s legs leave the ground at once.

This is called “pacing” and has the visual effect of making the giraffe seem to run in slow motion. In fact those long legs cover prodigious ground. The word giraffe comes from “zafarah,” Arabic for “one who walks swiftly.”

Excited as we were to return the stolen laptop, we didn’t intend to alarm the giraffe, but it was long gone. In short bursts, giraffes can put up speeds of 35 miles per hour. This one surely did.

The giraffe’s front legs are longer and stronger than its hindquarters. At a gallop, the power stroke of each front leg sends the neck moving from side to side, leaning ahead, swinging opposite its stride. No other animal has such a neck and no other animal’s neck is so deeply involved in forward movement.

•••••

Why such a striking neck in the first place?

Sixty years before Charles Darwin, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed that evolution proceeded from the accumulation of small, gradual, acquired characteristics. He wrote that the giraffe “is obliged to browse on the leaves of trees and to make constant efforts to reach them. From this habit … it has resulted that the animal’s forelegs have become longer than its hind-legs, and that its neck is lengthened….”

Had giraffes cried out for another explanation (and they didn’t, they just kept chewing acacia leaves), Darwin came along to give it a try. “The individuals which were the highest browsers and were able … to reach even an inch or two above the others, will often have been preserved. … These will have intercrossed and left offspring…. By this process long-continued … it seems to me almost certain that an ordinary hoofed quadruped might be converted into a giraffe.”

Lamarck’s and Darwin’s adherents still battle it out. Lamarck is lately staging a bit of a comeback.

Allow psychology professor David Barash to enter the debate and posit that they’re all wrong. To Barash it’s all about sex.

Younger males’ neck musculature grows visible in maturity, signaling their readiness to challenge for mating privileges. With females in estrus, male giraffes stand shoulder to shoulder and wield their necks as Barash puts it, “roughly like a medieval ball-and-chain weapon, or flail.”

They hammer each other neck-to-neck in turn until one cedes dominance. Barash speculates that longer necks lead to dominance, more mating opportunities, and so are passed along genetically. He calls it “necks for sex.”

Beyond the grand debate, there are simple enough ways to circumvent any generations-long path to giraffehood. Craig Holdrege, director of the Nature Institute, points out that to eat leaves, goats simply climb trees.

•••••

Baby giraffes are almost entirely vulnerable. At least half are killed before they reach their first birthday. Once in the Thula Thula Royal Zulu Game Reserve in Kwa-Zulu Natal, we came upon a newborn calf that only just reached its mother’s knees, far below her body. Mom kept it tight to her side and never took her eyes off us.

Baby giraffes are almost entirely vulnerable. At least half are killed before they reach their first birthday. Once in the Thula Thula Royal Zulu Game Reserve in Kwa-Zulu Natal, we came upon a newborn calf that only just reached its mother’s knees, far below her body. Mom kept it tight to her side and never took her eyes off us.

But protective maternal instincts can’t cover up the brutality of a baby giraffe’s birth. The calf drops head first some five and a half feet from the womb to the ground. Vulnerable as they are, calves get right to their feet, in as little as five minutes.

And they grow so fast! Cynthia Moss writes that they can grow nine inches in a single week. Oxford zoologist Dr. Jonathan Kingdon suggests this was “an early evolutionary strategy whereby very large, but relatively defenseless, animals were able to mitigate predation by growing too large for predators to overpower.”

•••••

Giraffes present as above it all, and not just physically. The biologist Richard Estes reckoned that of all the animals, giraffes give the least back to the curious viewer. Implacable, delphic stoicism, maintaining a stance, chewing and looking back at you.

I think Edith Wharton unknowingly spoke for giraffes: “Make one’s center of life inside of one’s self, not selfishly or excludingly, but with a kind of unassailable serenity – to decorate one’s inner house so richly that one is content there, glad to welcome anyone who wants to come and stay, but happy all the same when one is inevitably alone.”

These are the sentiments of any giraffe.

•••••

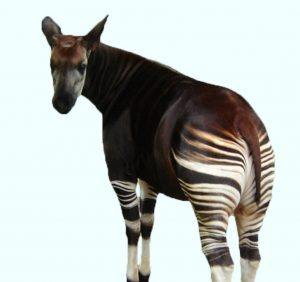

Giraffes are a safari favorite because of their utter evolutionary strangeness, but they have a little-known cousin that is stranger still – the okapi, the last large animal discovered by western science.

Further confined than the giraffe, to a single refuge in the Ituri forest in northeast Democratic Republic of Congo, the okapi is the national symbol of the DRC, but you will likely never see one except on the Congo’s 1000 Franc note.

An animal seemingly built by committee, this forest giraffe is donkeylike and tall-shouldered with a thick, elongated neck and chestnut black, glistening coat. Like the giraffe, it paces, and splays its legs while drinking. But the giraffe’s closest relative displays startling zebra-like stripes wrapping around its back end. Inexplicable.

An animal seemingly built by committee, this forest giraffe is donkeylike and tall-shouldered with a thick, elongated neck and chestnut black, glistening coat. Like the giraffe, it paces, and splays its legs while drinking. But the giraffe’s closest relative displays startling zebra-like stripes wrapping around its back end. Inexplicable.

The giraffe’s habitat has fragmented catastrophically (already extinct in seven countries, there are now less than 98,000 individuals left in the world). The okapi’s circumstance is more dire still. The Okapi Conservation Project’s John Lukas estimates there are only 3,000 to 3,500 okapi in the Ituri forest reserve. Lukas says okapi are so secretive and solitary that a ranger may walk 500 kilometers before sighting an okapi in the wild.

Henry Morton Stanley wrote of the okapi in 1887, prompting the British High Commissioner for Uganda to organize a search that failed to find a single animal. 100 years later, Lukas set up his facility at Epulu in Mbuti pygmy territory in the DRC in hopes of breeding okapi.

To get an idea how isolated opaki are, Lukas told me by email, “For the first 10 years we had to fly from Kinshasa to Goma and drive 5 days to get to our field station…. We built (an) airstrip in the middle 90’s but still drove from Goma getting supplies along the way. … In 2003 we started coming in from Uganda to Bunia and either driving or chartering a plane depending on the security along the road.”

For a time, fourteen okapi lived at the project reserve, but in 2012 all of the okapi – and six people – were killed in a two-day siege of the project, the bad guys apparently exacting retribution for a crackdown on the illegal ivory trade and illicit mining.

•••••

One afternoon near Naivasha, Kenya we bounded outside our LandCruiser, excited to behold the largest group of giraffes I have ever seen. We counted 23 on one side of the road and five on the other.

One afternoon near Naivasha, Kenya we bounded outside our LandCruiser, excited to behold the largest group of giraffes I have ever seen. We counted 23 on one side of the road and five on the other.

This was a crowning, exhilarating moment, but as exuberant as the humans may have been the giraffes declined comment, silently cud-chewing, mild-mannered, staring you down, sizing you up, batting an eyelash, inscrutable. Their long curly eyelashes suggested a certain sensitivity.

Like elephants, giraffes and okapi communicate with infrasound, low frequency tones inaudible to humans (and in the case of okapi, inaudible to their main predator, the leopard). Perhaps infrasound accounts for some of the giraffe’s aloof silence. After sixty years of field work, there is still a lot we don’t know.

From afar, giraffes stand out as masts on a dusty sea, triangles on the plain. Watch at distance their stately traverse, waves of heat rising from the savanna. In Karen Blixen’s words, “When cruising, with its gaze on the horizon and high center of gravity, the giraffe hardly seems in contact with the earth.”