by Joshua Wilbur

The 2020s will have a name. In the nursing homes of the future, Millennials’ grandchildren will hear all about the coming decade. Gran will remove her headset, loaded out with VR-entertainment and the latest in biometric tech, and she’ll tell the kids about the world as it was in the third decade of the 21st Century. For now, we look ahead to the Twenties, a decade certain to be charged with meaning, roaring in one way or another.

The 2020s will have a name. In the nursing homes of the future, Millennials’ grandchildren will hear all about the coming decade. Gran will remove her headset, loaded out with VR-entertainment and the latest in biometric tech, and she’ll tell the kids about the world as it was in the third decade of the 21st Century. For now, we look ahead to the Twenties, a decade certain to be charged with meaning, roaring in one way or another.

Our current moment isn’t easy to define. Since the start of the new millennium, there’s been much confusion about what to call the times. First, there’s the period from 2000 to 2009. Was it the “Two Thousands,” the “Zeroes,” the “ohs,” the “aughts,” or the “noughties?” None of the above, it seems: a name never really caught on. In 2010, looking back on the decade past, a number of commentators remarked on this fact, as will surely happen again in 2020 when retrospectives are faced with a similar semantic problem. Rebecca Mead, writing for the New Yorker in January 2010, noted: “[…] the decade just gone by remains unnamed and unclaimed, an orphaned era that no one quite wants to own, or own up to—or, truth be told, to have aught else to do with at all.”

The same can and will be said for the current decade, and with a similar feeling of embarrassment. The “Twenty Tens,” the “Tens,” “the Twenty Teens,” the “Teens?” Again, we lack a name with real currency. The “Teens,” like the teenagers of stereotype, resist description and brim with angst.

Maybe it’s too soon to declare our decade unnamed and unnamable. With the benefit of hindsight, perhaps the period from 2010 to 2019 will acquire a title and, with it, an identity. History, though, suggests otherwise.

Consider the 1900s. You might notice an immediate problem: am I referring to the century in sum or to the first decade of the twentieth century? Once we sort out the ambiguity and confirm the latter, ask yourself what happened during this span of time, from 1900 to 1909. It was the decade of…well, of what?

The Wright brothers flew the first airplane in 1903, and Einstein published his theory of special relativity in 1905. Wars were fought in the Philippines and Manchuria. Teddy Roosevelt carried a big stick. As for the decade on the whole, a narrative is haphazardly expressed: something about industrial and imperial ambitions.

The 1910s (the “Teens?”) fare better, but not by much. With the help of James Cameron, you might conjure an image of the sinking Titanic. The Spanish flu resulted in the death of tens of millions. So did World War I, the defining event of the decade. The Great War (the “War to end all Wars”) lends the 1910s a clearer identity, but as a stained decade, a blight on Western progress. In light of the war, Freud famously altered his psychoanalytic theory to include the death drive, an unconscious human impulse to destroy, so necrotic and senseless were the horrors of the Western Front. To many in Europe and abroad, the world appeared in a different light following the shock of the war.

And yet the decade remains unnamed, forever the 1910s. High school teachers sprint through curriculums to arrive at a more familiar place, to join Jay Gatsby’s party—with its flappers and illegal booze—before everything comes crashing down on Black Tuesday, 1929. The opulence of the Twenties gives way to the Great Depression of the Thirties, the gritty heroism of the Forties, the suburban daydream of the Fifties, the social upheaval of the Sixties, and so on. Over the course of the century, a story unfolds, with the decades serving as individual chapters. How did a unit of time come to loom so prominent in the popular imagination? And why were the 1900s and 1910s left behind?

Jason Scott Smith, a professor of history at the University of New Mexico, explains the rise of the decade in an article titled “The Strange History of the Decade: Modernity, Nostalgia, and the Perils of Periodization.” In Smith’s account, a number of factors converged in the early twentieth century to render the decade the historical category of choice in modern America. First, the explosive rise of mass media and consumer culture transformed how people received information. Everywhere you looked in the 1910s and 20s, new channels of the “new” appeared, tantalizing the visual and auditory senses—radios in the home, movies at the theater, and magazines on the newsstand. It was a dramatic salvo in our great fight against boredom. There was also the increased accessibility of practical technologies like the automobile, the camera, and the telephone. Taken together, these changes contributed to a growing sensation that daily life was accelerating, that the years were swirling together, that one’s place in time was increasingly unmoored, uncertain, floating. Sound familiar?

“Chronophobia,” a vague feeling of anxiety about the passage of time, hovers over the early century’s art and thinking, from the paintings of Cubism to the literary works of modernist writers to the daring philosophies of Henri Bergson and Martin Heidegger. But it wasn’t only learned aesthetes like Marcel Proust who were “In Search Of Lost Time.” A sense of heightened time-consciousness was on everyone’s mind, induced by the standardization of time across vast distances, by the wholesale application of F.W. Taylor’s scientific management of workers, and by the ever-widening obsession with business and busyness, production and productivity. The fast life had been democratized, made available to all. When you’re always running late or out of time, the days, months, and years tend to accumulate into a hazy cloud. Faced with too much to see and too much to remember, Americans leaned on the decade for a much-needed crutch, a kind of mnemonic device for the masses. Modernity had become chaotic, and decades made recent history more readily intelligible.

Secondly, Smith points to nostalgia: the “good-old-days” effect. As life sped up, what people really wanted was to slow down: to relax and enjoy time with friends and family. And so Americans yearned for a “simpler, less frantic age.” With the decade in hand, they could more easily map their lives against the backdrop of world events and ponder their individual histories relative to the social whole. In contemplating one’s own life alongside the life of the nation, the tendency was to look backwards. Decades proved useful in answering an old question: How did we get here?

This brings us to the 1920s and 30s, when the forces of acceleration and nostalgia combined to create our modern understanding of the decade. If it seems like our imagining of the previous century doesn’t really begin until the Roaring Twenties, then that’s because, according to Smith, the Twenties “was the first decade to legitimate a ten-year span of time as a historical category.” Certainly, the concept of the decade existed prior to the Twenties: it’s safe to say that most Americans would have associated the 1860s with the Civil War, for example. But never before had a distinct set of ten years taken on such meaning. During the Great Depression, Americans looked back to the relative prosperity of the decade past, and the lustrous image of the Twenties began to crystalize.

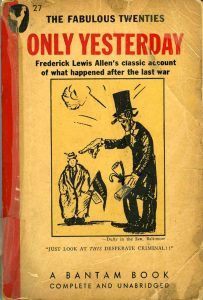

Further contributing to the perceived divide between the Twenties and Thirties was a widely read book by Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties, published in 1931. Allen chronicled the rise of popular culture (baseball, jazz, all things Gatsby-esque) and the shifting social landscape with the intention “to tell […] the story of what in the future may be considered a distinct era in American history.” In his account, Allen neatly bracketed the decade between the Great War and the Great Depression, offering an alluring picture of a country in transition. Much more than a measure of ten revolutions around the sun, the Twenties had become a container for cultural memory, a useful if flawed means of imparting structure onto the passage of time. The popular conception of “decade-as-history” grew in influence as the years flowed on, and the century took on a definite shape in the minds of the American public.

To this outline of the decade’s American history, I would add two points.

The first is that the named decade has come to shape our sense of ourselves just as much as it does our shared history. For today’s Westerners, two versions of time exist side-by-side: the objective time of everything and the subjective time of me. Here, too, the decade is a useful tool. It allows us to envision our individual histories in sets of ten, so that a middle-aged person can look back on his Twenties or ahead to his Fifties and paint a coherent self-portrait. A success narrative is often imposed relative to one’s current decade, as in: “I’m now in my Thirties—have I accomplished enough?”

Research supports the idea that we care deeply about decades. A 2014 study titled “People search for meaning when they approach a new decade in chronological age” demonstrated that “nine-enders,” people who are living the last year of a personal decade (ages 29, 39, 49, and so on), tend to be more self-reflective and take greater risks. First time participation in a running marathon, for example, spikes at these ages: a 29 year old is twice as likely to run a marathon than a 28 or 30 year old. A person aged 49 is almost three times more likely to run a marathon than someone aged 50. We measure our lives in decades, and people feel a unique pressure to succeed during moments of transition. As a culture, we’re on the cusp of just such a transition point.

For both individuals and society at large, some moments weigh heavier than others. The passage from 2019 to 2020 (an election year, as it happens) will feel more significant than the unremarkable move from 2009 to 2010, just as turning twenty feels more significant than turning ten. This may seem a trivial observation, but it suggests a final point about the ascendancy of some decades over others.

Units of time—which we often imagine to be objective in their own right, blank slates until marked by human action—are not created equal. In the case of the decade, the 1920s ring louder in cultural memory than the 1900s or 1910s not because more happened (if anything, the 1920s were less remarkable than the 1910s), but because the name (“Nineteen Twenties”) has been both easy to say and said often. In other words, our inclination to recall the past has been decided, in part, by an accident of language.

The same will be true of the coming Twenties when compared to the 2000s or the 2010s. Academics of the future will write with terse confidence about the new Twenties while “the first decade of the twentieth century” and “the 2010s” will be categorized according to the other common time-standard in American history: presidential incumbencies. From a distant perspective, we aren’t living in the Teens. Instead, students will learn of the Obama and Trump years. Then, the decadal pattern will repeat. The previous century offers no shortage of memorable decades with perfectly reusable names—eight of them to be exact—and, in our eagerness to periodize, sticking with a ready-made system presents the path of least resistance. The sweet-sounding 20s will be “in” while the clunky 2000s and 2010s will be “out,” known instead for three very different presidents and perhaps as a watershed moment in our addiction to tech.

As the current era comes to a close, there are reasons to be optimistic about the new Twenties. A decade with an identity is no bad thing, and not only because it will be much easier to speak of our favorite ‘20s music, movies, books, games, apps, and YouTube channels. Just as each named decade of the twentieth century has its own unique spirit, the 2020s will be defined by something, and there’s an opportunity for the earnest among us to be proactive about what that something might be. The Sixties might provide a model: change was in the air, as the cliché goes, and people embraced the moment.

The 2020s could be another such period of reform, a time of positive action. If the Trump years have taught us anything, it’s that a strong yearning for communal movement persists underneath the surface of our individual interests, if only we just knew how to move together. Maybe the idea of constructing the Twenties could serve as a rallying point for the majority of Americans who agree that climate change is real, war is terrible, and inequity is everywhere to be found.

More cynically, the revival of the named decade could be co-opted by the interests of greedy marketeers, as in the satirical vision of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, in which the years themselves are sponsored by corporate advertisers: the Year of the Whopper, the Year of the Trial-Sized Dove Bar, the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment. It’s not absurd to imagine Facebook dubbing the Twenties something like “the social decade,” which doesn’t sound too bad, despite being a veiled version of what Wallace lampooned. Of course, our perception of periodic time can also be twisted in far more sinister ways. September 11th lingers as the darkest example of all, a day that still unnerves each year.

Whatever comes of the 2020s, there’s something seductive about the idea of living through moments of historical significance, and a named decade only furthers our ability to mythologize shared and personal experiences. I feel a strange thrill during pivotal elections, sports championships, and—I’m ashamed to say it, though I doubt I’m alone in this—in the midst of havoc, during those moments when everyone huddles around the television or computer screen and asks, “Wait, what happened?” In the Twenties, there will be new trends to follow, new celebrities to watch, new presidents to critique. There will also be eruptions of violence and the sorts of disasters that are never forgotten. All of this shared history, good and bad, will be classified under the sheltering umbrella of the decade.

From another point of view, the Twenties will be a time of family dinners, missed appointments, workdays and weekends, rainy afternoons and sunny mornings. In the rhythmic current of daily life, things won’t feel much different. It will be in the looking back—in the remembering—that we will come to appreciate the usefulness of the named decade. Gran will think a moment and tell her story: “It would’ve been the early Twenties. We’d just voted Trump out, and your grandfather and I had bought a house, and…”