Francesca Angelini in The Times:

Lawrence Osborne’s death certificate hangs above his desk. “Tuberculosis, 2009,” he says with a laugh over the phone from Bangkok. It is the legacy of an article he wrote about men who fake their deaths for insurance payouts. It’s not hard to see why Raymond Chandler’s estate approached him to write a Philip Marlowe sequel: between writing assignments in seedy, dangerous places and a career spent drinking his way around Poland, Paris, Tuscany, California, New York, Mexico, Morocco, Istanbul and Bangkok, he is a match for Marlowe when it comes to dark and thrilling encounters.

Lawrence Osborne’s death certificate hangs above his desk. “Tuberculosis, 2009,” he says with a laugh over the phone from Bangkok. It is the legacy of an article he wrote about men who fake their deaths for insurance payouts. It’s not hard to see why Raymond Chandler’s estate approached him to write a Philip Marlowe sequel: between writing assignments in seedy, dangerous places and a career spent drinking his way around Poland, Paris, Tuscany, California, New York, Mexico, Morocco, Istanbul and Bangkok, he is a match for Marlowe when it comes to dark and thrilling encounters.

Yet his instinct was to say no. “You can never win with franchise books,” he says. “Even if you pull it off, fans are going to dump on you.” Osborne had idolised Chandler since he was young, but hadn’t forgotten how Robert B Parker was dismissed by Martin Amis in 1991 for turning Marlowe into “an affable goon”.

The story of the death certificate, though, had led Osborne to meet the model for Marlowe. “He was a retired private investigator living on the beach in a Thai village, making pizzas with a gun in his holster,” he recalls. “And I thought that if I based my Marlowe on him, and set the novel in a time and place I knew well, I could write something original, avoid pastiche.” He gave it a go. “It was like eating chocolate every day. And that’s not always the case when I’m writing, believe me. So, if people are going to piss on this, I don’t really care. I had fun with it.”

More here.

Theoretical physics has a reputation for being complicated. I beg to differ. That we are able to write down natural laws in mathematical form at all means that the laws we deal with are simple — much simpler than those of other scientific disciplines.

Theoretical physics has a reputation for being complicated. I beg to differ. That we are able to write down natural laws in mathematical form at all means that the laws we deal with are simple — much simpler than those of other scientific disciplines. “Comically befuddled, pompous, and ignorant … half nonsense, half banality … the kind of tedious crackpot that one hopes not to get seated next to on a train.”

“Comically befuddled, pompous, and ignorant … half nonsense, half banality … the kind of tedious crackpot that one hopes not to get seated next to on a train.” One rainy evening in December 1948, a blue Buick emerged from the darkness of the Venetian lagoon near the village of Latisana and picked up an Italian girl — 18, jet black wet hair, slender legs — who had been waiting for hours at the crossroads. In the car, on his way to a duck shoot, was Ernest Hemingway — round puffy face, protruding stomach and, at 49, without having published a novel in a decade, somewhat past his sell-by. He apologised for being late, and offered the rain-sodden girl a shot of whisky which, being teetotal, she refused.

One rainy evening in December 1948, a blue Buick emerged from the darkness of the Venetian lagoon near the village of Latisana and picked up an Italian girl — 18, jet black wet hair, slender legs — who had been waiting for hours at the crossroads. In the car, on his way to a duck shoot, was Ernest Hemingway — round puffy face, protruding stomach and, at 49, without having published a novel in a decade, somewhat past his sell-by. He apologised for being late, and offered the rain-sodden girl a shot of whisky which, being teetotal, she refused.

It feels as if the women on Dean’s list do have something important in common, but the precise nature of that something is surprisingly hard to pin down. They could not all be described, for one thing, as feminists: Sontag “roared” at Adrienne Rich about the “simple-mindedness” of feminism, having previously defended it, and Ephron felt “uneasy” about organized feminist efforts at the Democratic convention in 1972. Likewise, only some of these writers – Sontag and Arendt – were capital-I Intellectuals. Kael was a movie critic. McCarthy and Hurston were best known for their fiction. Adler is most famous for her reportage. The famously witty Nora Ephron, meanwhile, in addition to writing the screenplay for When Harry Met Sally and the gut-busting novel Heartburn, once wrote one hell of a parody of Ayn Rand:

It feels as if the women on Dean’s list do have something important in common, but the precise nature of that something is surprisingly hard to pin down. They could not all be described, for one thing, as feminists: Sontag “roared” at Adrienne Rich about the “simple-mindedness” of feminism, having previously defended it, and Ephron felt “uneasy” about organized feminist efforts at the Democratic convention in 1972. Likewise, only some of these writers – Sontag and Arendt – were capital-I Intellectuals. Kael was a movie critic. McCarthy and Hurston were best known for their fiction. Adler is most famous for her reportage. The famously witty Nora Ephron, meanwhile, in addition to writing the screenplay for When Harry Met Sally and the gut-busting novel Heartburn, once wrote one hell of a parody of Ayn Rand: In late 2009, representatives of the alcohol industry were summoned to parliament to

In late 2009, representatives of the alcohol industry were summoned to parliament to  When the Philippines opened its first school of forestry in 1910, the institute’s leaders hatched a plan to restore degraded woodlands surrounding the campus outside Manila. They planted dozens of tree varieties, both native and exotic. In 1913, the school received 1,012 mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) seeds from a botanical garden in Calcutta, India, and started growing them around the grounds. The American hardwood became such a staple of reforestation efforts in the country that it spread throughout natural areas, so much so that it eventually proved a nuisance. The trees create veritable green deserts: their tannin-rich leaves are unpalatable to local animals and seem to stifle the growth of other plants where they fall. They also produce seeds annually, giving them an advantage over native hardwoods, which do so at intervals of five years or more.

When the Philippines opened its first school of forestry in 1910, the institute’s leaders hatched a plan to restore degraded woodlands surrounding the campus outside Manila. They planted dozens of tree varieties, both native and exotic. In 1913, the school received 1,012 mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) seeds from a botanical garden in Calcutta, India, and started growing them around the grounds. The American hardwood became such a staple of reforestation efforts in the country that it spread throughout natural areas, so much so that it eventually proved a nuisance. The trees create veritable green deserts: their tannin-rich leaves are unpalatable to local animals and seem to stifle the growth of other plants where they fall. They also produce seeds annually, giving them an advantage over native hardwoods, which do so at intervals of five years or more. There is, by now, no separating the

There is, by now, no separating the  At the playground on the leafy campus of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, one afternoon in May, the mathematician Akshay Venkatesh alternated between pushing his 4-year-old daughter on the swing and musing on the genius myth in mathematics. The genius stereotype does the discipline no favors, he told Quanta. “I think it doesn’t capture all the different kinds of ways people contribute to mathematics.”

At the playground on the leafy campus of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, one afternoon in May, the mathematician Akshay Venkatesh alternated between pushing his 4-year-old daughter on the swing and musing on the genius myth in mathematics. The genius stereotype does the discipline no favors, he told Quanta. “I think it doesn’t capture all the different kinds of ways people contribute to mathematics.” Earlier this summer, a white poet named Anders Carlson-Wee published

Earlier this summer, a white poet named Anders Carlson-Wee published  But first things first. Magic’s Reason is based on a brilliant aperçu. Why shouldn’t anthropology come to terms with today’s secular magic? Or, to put that a little more carefully: given that anthropology has to a significant degree been constituted on an opposition between, on the one side, “modern rationality,” and, on the other, so-called “primitive magic” (as articulated by the discipline’s founders, and by E. B. Tylor [1832–1917] in particular), what might an ethnography of contemporary stage magicians and their understanding and practices of magic have to tell us about the discipline’s conceptual and ideological underpinnings?

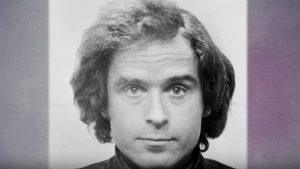

But first things first. Magic’s Reason is based on a brilliant aperçu. Why shouldn’t anthropology come to terms with today’s secular magic? Or, to put that a little more carefully: given that anthropology has to a significant degree been constituted on an opposition between, on the one side, “modern rationality,” and, on the other, so-called “primitive magic” (as articulated by the discipline’s founders, and by E. B. Tylor [1832–1917] in particular), what might an ethnography of contemporary stage magicians and their understanding and practices of magic have to tell us about the discipline’s conceptual and ideological underpinnings? When Ted Bundy was apprehended in Pensacola in the early hours of February 15, 1978, six weeks after he escaped from a Colorado jail, the FBI had already publicly linked him to thirty-six murders across five states. In the ensuing decade, both the random speculations of onlookers and the educated guesses of law enforcement often pushed the number far higher. Many said it had to be a hundred or more, and cited Bundy’s own enigmatic statement to the Pensacola detectives who had questioned him about the FBI’s claim. “He said the figure probably would be more correct in the three digits,” Deputy Sheriff Jack Poitinger said.

When Ted Bundy was apprehended in Pensacola in the early hours of February 15, 1978, six weeks after he escaped from a Colorado jail, the FBI had already publicly linked him to thirty-six murders across five states. In the ensuing decade, both the random speculations of onlookers and the educated guesses of law enforcement often pushed the number far higher. Many said it had to be a hundred or more, and cited Bundy’s own enigmatic statement to the Pensacola detectives who had questioned him about the FBI’s claim. “He said the figure probably would be more correct in the three digits,” Deputy Sheriff Jack Poitinger said. Amid all the hot, languid days of late August, melting together into a lifetime’s haze of forgotten moments, what happened exactly a half-century ago will never fade: I’m tightly holding the hand of a girl I’ve only just met, fleeing the searing sensation of tear gas, coughing and wheezing, caught up in the crowd stampeding out of Grant Park down Michigan Avenue.

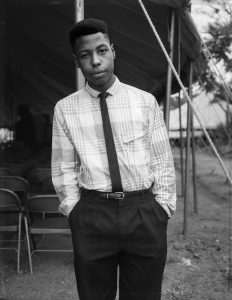

Amid all the hot, languid days of late August, melting together into a lifetime’s haze of forgotten moments, what happened exactly a half-century ago will never fade: I’m tightly holding the hand of a girl I’ve only just met, fleeing the searing sensation of tear gas, coughing and wheezing, caught up in the crowd stampeding out of Grant Park down Michigan Avenue. He opened a book of Dawoud Bey’s photographs at random. The images were of people of color, not unlike himself, and what he loved about the images was how the subjects held their own self-validation in their hands, their eyes, without being reduced to an ideology—you know, equating blackness with nobility, that kind of thing. It was such a relief, to see works of art made out of real lives. The pictures named a world he knew, even as he struggled to understand it more. And, even though the pictures hadn’t been shot in Ferguson, Staten Island, or Cincinnati, they shimmered with lives—black male lives. Generally, the language around that familiar and unfamiliar form has little to do with his humanity and more to do with the pressure points—guilt, remorse, and so on—his dead or living self aggravates. And, because he’s less interesting in the context of joy, the continued violence to his body. Under his white shirt, he knew something about that. And this: that the violence inflicted on the black male body didn’t stop there but extended, of course, to his community, which includes mothers and brothers and all the people who never considered him invisible or trivial or tragic or extinguishable to begin with.

He opened a book of Dawoud Bey’s photographs at random. The images were of people of color, not unlike himself, and what he loved about the images was how the subjects held their own self-validation in their hands, their eyes, without being reduced to an ideology—you know, equating blackness with nobility, that kind of thing. It was such a relief, to see works of art made out of real lives. The pictures named a world he knew, even as he struggled to understand it more. And, even though the pictures hadn’t been shot in Ferguson, Staten Island, or Cincinnati, they shimmered with lives—black male lives. Generally, the language around that familiar and unfamiliar form has little to do with his humanity and more to do with the pressure points—guilt, remorse, and so on—his dead or living self aggravates. And, because he’s less interesting in the context of joy, the continued violence to his body. Under his white shirt, he knew something about that. And this: that the violence inflicted on the black male body didn’t stop there but extended, of course, to his community, which includes mothers and brothers and all the people who never considered him invisible or trivial or tragic or extinguishable to begin with. Let’s be optimistic and assume that we manage to avoid a self-inflicted nuclear holocaust, an extinction-sized asteroid, or deadly irradiation from a nearby supernova. That leaves about 6 billion years until the sun turns into a red giant, swelling to the orbit of Earth and melting our planet. Sounds like a lot of time. But don’t get too relaxed. Doomsday is coming a lot sooner than that. The Earth is, in some ways, in a precarious spot in the solar system. There’s a range of orbital distances inside which a planet can have both liquid surface water (which is believed to be necessary for life) and enough atmospheric CO2 to carry on photosynthesis. This range is called the photosynthesis habitable zone. The Earth orbits barely within the sun’s zone. Some scientists estimate that the inner edge lies just 7.5 million kilometers away, which is only 5 percent of the distance between the Earth and the sun.

Let’s be optimistic and assume that we manage to avoid a self-inflicted nuclear holocaust, an extinction-sized asteroid, or deadly irradiation from a nearby supernova. That leaves about 6 billion years until the sun turns into a red giant, swelling to the orbit of Earth and melting our planet. Sounds like a lot of time. But don’t get too relaxed. Doomsday is coming a lot sooner than that. The Earth is, in some ways, in a precarious spot in the solar system. There’s a range of orbital distances inside which a planet can have both liquid surface water (which is believed to be necessary for life) and enough atmospheric CO2 to carry on photosynthesis. This range is called the photosynthesis habitable zone. The Earth orbits barely within the sun’s zone. Some scientists estimate that the inner edge lies just 7.5 million kilometers away, which is only 5 percent of the distance between the Earth and the sun.