by Holly Case and Lexi Lerner

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus.

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus.

***

In its most basic iteration, a circus is a ring or circle. The Circus Maximus in Ancient Rome was an oval-shaped track used for chariot races. Presbyterian minister Conrad Hyers writes that the modern circus has a “willingness to encompass and make use of the whole human spectrum”:

The costumed beauty rides on the lumbering beast or walks hand in hand with the ugly dwarf. The graceful trapeze artist soars high above the stumbling imitations of the clown in the ring below. Nothing and no one seem to stand outside this circumference, this circus.

***

From a 1930 program for Krone Circus in Vienna: a Roman-style chariot race, gladiator games, Eskimos and polar bears, a parade of twenty elephants, springing Arabs, “The Maharadja’s Grand Entrance,” an “Exotic procession,” the Chinese troupe of Wong Tschio Tsching, and Cossack riders. (“No smoking. No dogs allowed.”)

***

The circus often starts by breaking its own rules. Paul Bouissac, a semiotician at the circus, explains. A master juggler is poised to begin the opening act, but he is interrupted by a clown who appears among the audience–introducing himself, fumbling, stealing a child’s popcorn, all the while defying the warnings and threats of the Master of Ceremonies. “From the beginning,” writes Bouissac, “as a kind of foundational gesture, this clown has defined himself as a rule breaker.”

He has mocked good manners. He has transgressed even the circus code of which he is a part. But his tricks have made people happy. He has denounced the arbitrariness of authority. When the Master of Ceremonies wants to throw him out of the ring, the audience spontaneously boos…

Eventually, the clown is removed and the juggler can begin his act. “At the end,” Bouissac concludes, “the triumph of the juggling hero will be both physical and social.” But this satisfying resolution can only take place after the clown has created a problem. The juggler’s act is only triumphant within “the framing provided by the clown.”

***

A magician never explains a trick; clowns often do. In the words of William Zinsser, writing for Life in 1970: “If knavery is pouring water down the pants of ‘the victim’ (and it is), surprise is when the victim shows no reaction to this indignity and then pulls from his pants a rubber bottle into which all the water has flowed.” The “real purpose” of this “constant revealing of secrets,” Zinsser continues, “is to restore everything to normal.”

Clowns are destroyers of order. They gratify us with their outlandish raids on all that is tidy and respectable; they do what we would like to do, but which we have been told is ‘not done.’ Eventually, however, the disarray makes us nervous, so the clown puts everything back.

***

What makes clowns so creepy? ponders a neuroscientist. “Human faces that deviate from the norm are upsetting. And clown faces differ in very elaborate ways; the huge painted-on smiles, the crude colours, the greatly-exaggerated eyes, all of these and more combine to provide a recognisably-human face which doesn’t behave as it should, which is very unsettling on a deep subconscious level. This is doubly true if the painted-on expression doesn’t match the actual one.”

***

The 1928 silent film The Man Who Laughs begins with King James II sentencing a political enemy to death. The enemy’s son, Gwynplaine, is kidnapped by “gypsy traders” who notoriously turn children into “monstrous clowns and jesters.” The traders surgically mutilate Gwynplaine’s face so it appears to be perpetually smiling, to “laugh forever at his fool of a father.”

When Bill Finger, Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson were constructing villains for the Batman franchise, they twisted the countenance of this “absolutely weird” Man Who Laughs to make him “look a little clown-like… And that was the Joker!” In a scene from The Dark Knight, the Joker appears dressed in a nurse’s uniform with clown makeup and a gun to his own head. “Introduce a little anarchy, upset the established order, and everything becomes chaos,” he says, licking his lips and chuckling.

***

Asked about how he came up with the idea for the horror villain Pennywise in his novel It (1986), Stephen King said: “‘There [ought] to be one binding, horrible, nasty, gross, creature kind of thing that you don’t want to see, [and] it makes you scream just to see it.’ So I thought to myself, ‘What scares children more than anything else in the world?’ And the answer was ‘clowns.’”

***

In Circus Day (1903), two young boys, Joe and Shaver, enter the menagerie tent. Passing “the leopard, the lions, the tiger, and the other wild animals pacing up and down in the cages,” and pausing before the monkey cage: “They look just like some people,” Shaver says, as an old gray monkey takes hold of a young one and boxes its ears.

***

Henry North Ringling (of Ringling Bros. fame) writes: “When the trainer starts off, the animals are all chained to their pedestals, and ropes are put around their necks to choke them down and make them obey. All sorts of other brutalities are used to force animals to respect the trainer and learn their tricks. The animals work from fear.”

***

When Karli Rebernigg of the Austrian National Circus began working with lions and tigers in the 1930s, the training was based on Gewalt und Wildheit (violence and savagery). Rebernigg says he developed a new form of Loewendressur (lion dressage) based on love and understanding. As of 1946, “things that were formerly indispensable in the main cage,” such as “revolver shots, the lash of the whip, and loud banging,” were “largely absent” from Rebernigg’s performances. How does he explain the bite and scratch scars on his body? As the products of “playful pranks rather than mean tricks.”

***

Andrea Marais-Potgieter, a South African graduate student in Ecopsychology, writes: “If South Africa is to move forward we need to eradicate all remaining contortions of oppression in our society, starting with the circus.”

***

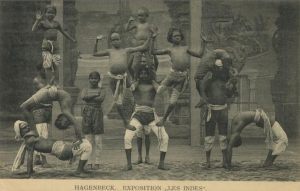

During the 1870s, the animal exhibitions of European circus giant Carl Hagenbeck were tanking. Faced with a surfeit of competitors, accelerating “production” of exotic beasts, and plummeting prices, Hagenbeck sought a way to “struggle through with honor.” He shared his plans to bring reindeer to continental Europe with his dear friend, Heinrich Leutemann. If you bring Lapland reindeer, why not “Laplanders,” too? Leutemann asked.

After “some difficulties herding the reindeer through the Hamburg streets—which, of course, furthered public notice,” the Lapland “people show” took off. Hagenbeck had to open an extra guarded entrance to accommodate the “throngs” and “droves” of viewers.

After “some difficulties herding the reindeer through the Hamburg streets—which, of course, furthered public notice,” the Lapland “people show” took off. Hagenbeck had to open an extra guarded entrance to accommodate the “throngs” and “droves” of viewers.

Later human circus exhibitions toured Berlin, London, Paris, and beyond. One show had over sixty thousand attendees. Another was attended by the Austrian Kaiser Franz Josef himself.

***

The Hagenbeck people shows […] made ‘Hagenbeck’ a household name—a name that would eventually become more and more known as Hagenbeck applied what he had first learned from exhibiting people to his later exhibits of animals.

Today Hagenbeck is most famous for the “Hagenbeck revolution” in zoo architecture, keeping animals in moat-enclosed land patches rather than barred cages. His zoo in Hamburg is still open seven days a week, nine hours a day. One recent Google Review reads, “It’s a great way to spend a day among animals we Europeans don’t get to see live.”

***

***

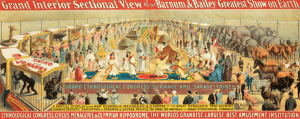

In the Barnum & Bailey circus, Appoo Hamid, an Indian dwarf “who was said to represent the lowest type of the human race yet discovered,” eventually committed suicide. So did Ota Benga, who moved from the Congo to the Bronx Zoo to a circus to the Colored Orphan Asylum. When hopes of returning to the Congo ran dry, Benga shot himself in the heart.

***

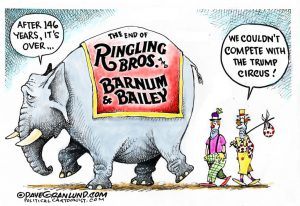

Earlier this year, a New York Times op-ed contributor wrote: “[I]f Barnum were alive today, he might be interested in exhibiting Mr. Trump: not as a paragon of business acumen, political prowess or any of the other main attractions in the circus of contemporary life, but as an extreme embodiment of humbug — worthy of a sideshow, perhaps, but nothing more.”

***

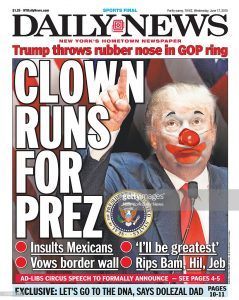

On Independence Day 2018, The New York Daily News blared the headline: THE CLOWN WHO PLAYS KING, with a doctored image of Donald Trump frowning while wearing classic red and white clown makeup.

On Independence Day 2018, The New York Daily News blared the headline: THE CLOWN WHO PLAYS KING, with a doctored image of Donald Trump frowning while wearing classic red and white clown makeup.

Other Daily News covers: CLOWN RUNS FOR PRES and DEAD CLOWN WALKING. One journalist wrote in an opinion column from 2014 that despite recent reports of a shortage of clowns, “The clowns just ran away from the circus. To join politics.”

Take Donald Trump. Trumpy the Clown is a three-ring natural—silly orange hair and so bigfooted that even after making a laughingstock of himself in the President Obama ‘birth certificate’ hysteria and serving as a rodeo clown in the presidential election long enough to boost his TV ratings, he now says he wants to run for governor of New York.

***

At a Florida campaign rally for Trump in November 2015, the Grand Old Party was joined by a real, live pachyderm. Essex the elephant, led by a notorious handler of the Picadilly Circus (formerly indicted for animal cruelty), had the message “Trump—Make America Great Again” chalked on her side in white capital letters.

***

In Chinese equestrian theater—sometimes called hippodrama—horses were often themselves actors playing roles in a dramatic spectacle. The Countess Mathilde Pauline Nostitz rode a retired circus horse through British Burma in 1838. The horse had earlier played a buffoon in the Chinese circus.

***

***

“Everybody wants to see the trapeze guy fall off and the lion trainer killed,” said Alexander Lacey, former Ringling big cats trainer.

***

P. T. Barnum’s 1891 obituary calls his last name “a proverb,” one that represents the “comedy of a harmless deceiver and the willingly deceived.” He was most famous for the line: “There’s a sucker born every minute,” which he never actually said.

***

A famous quote by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin goes: “For as long as the people are illiterate, the most important among all the arts for us are the cinema and the circus,” which–like Barnum–he never actually said.

***

According to Yakov Peters, one of the founders of the notorious Bolshevik secret police, the Cheka: in 1918, a popular clown duo by the name of Bim Bom made fun of the Bolsheviks during a circus performance in Moscow. Some overzealous Chekists in the audience immediately placed Bim Bom under arrest. Believing the arrest was part of the show, the audience laughed. Bim made a run for it and the Chekists opened fire.

***

The circus meant a great deal to the Soviets. The Bolshevik Leon Trotsky gave fiery speeches at the “Modern” circus grounds, which were “always packed with crowds of people.” Following the Russian Revolution, the first modern classless society nationalized the circus and rebranded it as high-class entertainment. Training for circus performers was formalized with the establishment of the Moscow State College of Circus and Variety Arts, the first of its kind in the world. “Before the Revolution we were considered the lowest of all the entertainers,” one performer recalled in the 1940s. “Now we are among the most beloved performers in our whole country.”

***

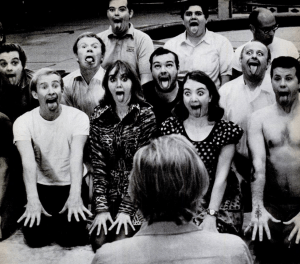

When a journalist for Life visited the new Ringling Clown College in Sarasota, Florida in 1970, there were 25 students, 13 of them graduating with contracts for Ringling’s next season. As part of their education, the students dutifully studied the six elements of circus clowning: blows, falls, knavery, stupidity, mimicry, and surprise.

***

In 1988, a Soviet trapeze artist told a Western journalist that she turned down offers to dance with the Bolshoi Ballet twice in favor of the circus, “a more universal art, of greater importance.”

***

By way of explaining what was special about the Chinese circus, its artistic director Deng Baojin told a Hungarian interviewer in 2004: “Western man wants to subjugate the world, to form it in his own image. The man of the East does not do this. We believe we are a part of nature and that we must integrate ourselves into its eternal order.”

***

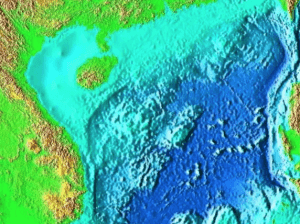

The French word for circus is cirque, which also refers to a geological formation resembling an amphitheater, often formed by a receding glacier. A spattering of late nineteenth century French sources refer to a “cirque chinois” (not to be confused with a Chinese circus), an amphitheater-like valley now largely submerged, forming the Gulf of Tonkin and the South China Sea.

The French word for circus is cirque, which also refers to a geological formation resembling an amphitheater, often formed by a receding glacier. A spattering of late nineteenth century French sources refer to a “cirque chinois” (not to be confused with a Chinese circus), an amphitheater-like valley now largely submerged, forming the Gulf of Tonkin and the South China Sea.

Yet no other recent sources refer to the area as a cirque. A geologist at the United States Geological Survey writes: “The Gulf of Tonkin is not a cirque in the geological sense (but one might consider it something of a circus in the political sense).”

***

During the Cultural Revolution in Maoist China (1966-1976), circuses with animals and Russian acrobats were banned to prevent “worshipping foreign culture.” The Shanghai Circus became a staging ground for the humiliation of “enemies,” who were beaten and berated by Red Guards, sometimes before crowds numbering in the thousands.

***

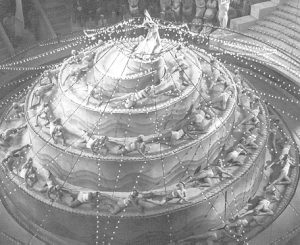

During the Great Terror, Soviet moviegoers delighted in the spectacular musical Tsirk (Circus, 1936), featuring the grande dame of Soviet cinema, Lyubov Orlova. She played an American circus performer forced to flee the United States for mysterious reasons. While on tour in the Soviet Union, her character falls in love with a hero of the Soviet circus. A grand circus finale unfolds with an enormous multi-tiered, rotating cake ringed with gymnasts and lights.

Interrupting the scene, a German in a long overcoat, a dark comb-over, and a Hitler moustache threatens to spoil the show. He announces the woman’s guilty secret: she has a black child. (“Черный ребенок, Господа!”—“A black child, ladies and gentlemen!”) He holds up the child, grimacing in anticipation of the outraged response.

“So what?” says the Soviet ringmaster, and the child is taken up by the audience as the German is booed and catcalled off the scene. Then the focus returns to the boy, as the circusgoers pass him up the stands, singing a lullaby in the different languages of the Soviet Union. The lullaby swells into the “Song of the Motherland,” written for the film, but soon to become the unofficial anthem of the Soviet Union:

For us there are no ‘blacks’ or ‘coloreds.’

[…]

From our table no one is excluded,

Each is awarded on merit,

In golden letters we write

The law of the people, of Stalin.

[…]

Wide is my Motherland,

Of her many forests, fields, and rivers!

I know of no other such country

Where a man can breathe so freely.

***

“Like a three-ring circus, each trial was more flamboyant than its predecessor, with increasingly lurid accusations and confessions,” writes historian Paul Flewers of the Moscow Show trials of 1936 to 1938. The trials and the Great Terror resulted in the arrest and deportation or execution of over a million Soviet citizens.

***

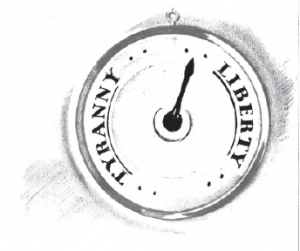

During the World Cup tournament in Russia this summer, Maxim Trudolyubov overhead local Muscovites wager that the nation’s soccer success could lead to “increasing taxes, raising the retirement age, even starting another war.” One said: “If Russia gets to semifinals, they will reintroduce serfdom.” Trudolyubov writes: “These jokes are remarkable in their sober assessment of the kind of trade-off the Kremlin is offering to the Russian public: If we give you enough bread and circuses, don’t be surprised if further freedoms and rights are taken from you.”

***

In the Roman Empire, rulers operated on the “bread and circus” principle. When bread was scarce, circuses were used to divert the masses. But the circuses of Rome were no Barnum and Bailey affairs. Men of weak and defenseless groups were thrown to the lions, and scores of these victims were Christians.

This passage comes from a pamphlet published by an organization called the Citizenship Educational Service, Inc. Its chairman was Theodore Roosevelt, son of the late president by the same name. The group’s mandate: “making American democracy more real and vital [and] resisting any propaganda designed to undermine faith in our democratic institutions.”

Its legacy consists mainly of this one pamphlet, titled Footprints of the Trojan Horse: Some Methods Used by Foreign Agents Within the United States (1940). It warns against “traitors to democracy, who seek to stir up panic and internal strife by setting neighbor against neighbor, group against group, religion against religion.”

The record of the last 2,000 years of history has provided us with one unmistakable storm warning when human rights are in danger—a campaign against minorities. […] Under the smoke screen of group hatred, unscrupulous elements attain objectives destructive to our common interests.

***

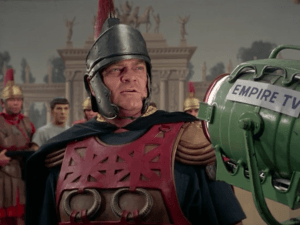

Captain’s log, stardate March 15, 1968:

In a Star Trek episode titled “Bread and Circuses,” crew members of the Starship Enterprise find a planet—a “parallel world” to Earth—where the Roman Empire has survived into the twentieth century. A magazine features an ad for a “Jupiter 8” Buick-cognate and everyone’s name ends in “-us” (Septimus, Merikus, Claudius, Flavius). Circus games—pitting dissidents against experienced arena fighters in sword fights to the death—are televised with fake applause and boos.

The planet’s proconsul touts this “conservative world based on time-honored Roman strengths and virtues” as superior; there has been no war here in over four hundred years.

“Interesting,” Spock says, raising an eyebrow, “I find the checks and balances of this civilization quite illuminating… They do seem to have escaped the carnage of your first three world wars.”

Dr. McCoy interrupts, outraged: “They have slavery, gladiatorial games, despotism…”

“Situations quite familiar to the six million who died in your First World War, the eleven million who died in your Second, the thirty-seven million who died in your Third,” Spock counters. “Shall I go on?”

Later Spock and McCoy are brought to the studio “arena” to fight against gladiators as Captain Kirk is forced to watch from the proconsul’s platform. Spock can hold his own; Dr. McCoy is struggling. The fight slackens and the volume on the audience cat-call is cranked up. A centurion guard on the sidelines whips the gladiator and raises a finger in warning: “You bring this network’s ratings down, Flavius, and we’ll do a special on you!”

Starfleet has a regulation prohibiting interference in other civilizations, so after a sex scene between Kirk and a slave woman (“For this evening I was told I am your slave”) and a brief struggle with the guards, the three starship crew members are beamed out.

***

In its most basic iteration, a circus is a ring or circle. “Nothing and no one seem to stand outside this circumference, this circus.”