Joanna Biggs in The New Yorker:

You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK,” Kailash, the protagonist of Amitava Kumar’s new nonfiction novel, “Immigrant, Montana” (Knopf), says of his fellow New Yorkers. “You look at him and think that he wants your job and not that he just wants to get laid.” In 1990, Kailash arrives in New York City from the eastern-Indian city of Ara to study literature; sex for him has gone only as far as a fleeting topless shot at the movies before the censor’s cut. John Donne, in “To His Mistress Going to Bed,” imagined his lover’s body as his America, awaiting discovery; Kailash is hopeful that America the beautiful can be explored through its women’s bodies.

You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK,” Kailash, the protagonist of Amitava Kumar’s new nonfiction novel, “Immigrant, Montana” (Knopf), says of his fellow New Yorkers. “You look at him and think that he wants your job and not that he just wants to get laid.” In 1990, Kailash arrives in New York City from the eastern-Indian city of Ara to study literature; sex for him has gone only as far as a fleeting topless shot at the movies before the censor’s cut. John Donne, in “To His Mistress Going to Bed,” imagined his lover’s body as his America, awaiting discovery; Kailash is hopeful that America the beautiful can be explored through its women’s bodies.

Getting laid has always been a way that outsiders have attempted to conquer (and to write about) the big city, from Tom Jones to Frédéric Moreau to Alexander Portnoy. Kumar himself arrived at Syracuse University in the late eighties from Delhi via Ara; he is now a professor at Vassar and has written six books of nonfiction, one of poetry, and a previous novel. The new book falls between genres. Its aim is not to tell a story, exactly, but to create a portrait of a mind moving uneasily between a new, chosen culture and the one left behind. Kailash’s journey toward sexual integration in the West is cast (to quote the author’s note) as “a work of fiction as well as nonfiction, an in-between novel by an in-between writer,” complete with multiple epigraphs, pictures, footnotes academic and digressive, and both pop-cultural and literary-theoretical references. So the form of “Immigrant, Montana” calls to mind works by Teju Cole (to whom the book is dedicated), Sheila Heti, and Ben Lerner. Can we believe in the immigrant who happens to write in the hippest, Brooklyniest form going? What sort of outsider knows the rules so preternaturally well?

More here.

If you consider yourself to have even a passing familiarity with science, you likely find yourself in a state of disbelief as the president of the United States calls climate scientists “

If you consider yourself to have even a passing familiarity with science, you likely find yourself in a state of disbelief as the president of the United States calls climate scientists “ It is widely believed that most Republicans are skeptical about human-caused climate change. But is this belief correct?

It is widely believed that most Republicans are skeptical about human-caused climate change. But is this belief correct? Water attracts trouble. Time and again this ubiquitous and vital substance becomes the subject of controversial claims. The latest is about “raw” or “live” water, consumed directly from natural springs with no treatment or purification.

Water attracts trouble. Time and again this ubiquitous and vital substance becomes the subject of controversial claims. The latest is about “raw” or “live” water, consumed directly from natural springs with no treatment or purification. To that end, First Reformed is daring and unrelenting—it searches for and pinpoints real harm. Ten people walked out of the theater where I saw it, most of them Schrader’s age. I think they left because the film’s intensity was too much in a world where they had the option of seeing Book Club at a theater down the street.

To that end, First Reformed is daring and unrelenting—it searches for and pinpoints real harm. Ten people walked out of the theater where I saw it, most of them Schrader’s age. I think they left because the film’s intensity was too much in a world where they had the option of seeing Book Club at a theater down the street. Sunday, late July: the small suburban towns of Persan and Beaumont-sur-l’Oise are almost empty. Persan, the last stop on the H line, is half an hour from the Gare du Nord, through a landscape of woodland and fields. It was a beautiful day. A man was fishing by the banks of the Oise; two others were chatting in front of a hairdresser’s salon. The day before, thousands of people from Paris and the banlieues had filled the streets; some had arrived by bus from further afield, among them party leaders from the left-wing NPA and La France Insoumise, anti-racist activists, relatives of people who had been killed by the police, girls wearing T-shirts saying ‘Justice for Adama’ or ‘Justice for Gaye’, and a man with a placard: ‘The State protects Benallas, we want to save Adamas.’

Sunday, late July: the small suburban towns of Persan and Beaumont-sur-l’Oise are almost empty. Persan, the last stop on the H line, is half an hour from the Gare du Nord, through a landscape of woodland and fields. It was a beautiful day. A man was fishing by the banks of the Oise; two others were chatting in front of a hairdresser’s salon. The day before, thousands of people from Paris and the banlieues had filled the streets; some had arrived by bus from further afield, among them party leaders from the left-wing NPA and La France Insoumise, anti-racist activists, relatives of people who had been killed by the police, girls wearing T-shirts saying ‘Justice for Adama’ or ‘Justice for Gaye’, and a man with a placard: ‘The State protects Benallas, we want to save Adamas.’ On the surface, the new book by Julie Hedgepeth Williams, Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes, is the story of the long and winding genesis of literary culture in the post-Civil War American South. One of the “not-so-ordinary Joes” referred to in the title is, after all, Joel Chandler Harris (whose childhood nickname was Joe), author of the Uncle Remus stories that sold astoundingly well both in postwar America and around the world and influenced an entire generation of writers, playing a large role in creating a distinctive Southern literary tradition. But in addition to that surface story, there’s also a deeper narrative thread winding its way through “Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes,” a narrative about the unpredictable, often byzantine connections that thread their way from one literary generation to another. In this case, Williams quite delightfully traces this thread through the same name, linking two generations of 19th-century American Southerners with a namesake from 18th-century England, a man who never knew anything about either of them or about the American South itself.

On the surface, the new book by Julie Hedgepeth Williams, Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes, is the story of the long and winding genesis of literary culture in the post-Civil War American South. One of the “not-so-ordinary Joes” referred to in the title is, after all, Joel Chandler Harris (whose childhood nickname was Joe), author of the Uncle Remus stories that sold astoundingly well both in postwar America and around the world and influenced an entire generation of writers, playing a large role in creating a distinctive Southern literary tradition. But in addition to that surface story, there’s also a deeper narrative thread winding its way through “Three Not-So-Ordinary Joes,” a narrative about the unpredictable, often byzantine connections that thread their way from one literary generation to another. In this case, Williams quite delightfully traces this thread through the same name, linking two generations of 19th-century American Southerners with a namesake from 18th-century England, a man who never knew anything about either of them or about the American South itself. It’s harder than you might think to make a dinosaur. In Jurassic Parkthey do it by extracting a full set of dinosaur DNA from a mosquito preserved in amber, and then cloning it. But DNA degrades over time, and to date none has been found in a prehistoric mosquito or a dinosaur fossil. The more realistic prospect is to take a live dinosaur you have lying around already: a bird. Modern birds are considered a surviving line of theropod dinosaurs, closely related to the T rex and velociraptor. (Just look at their feet: “theropod” means “beast-footed”.) By tinkering with how a bird embryo develops, you can silence some of its modern adaptations and let the older genetic instructions take over. Enterprising researchers have already

It’s harder than you might think to make a dinosaur. In Jurassic Parkthey do it by extracting a full set of dinosaur DNA from a mosquito preserved in amber, and then cloning it. But DNA degrades over time, and to date none has been found in a prehistoric mosquito or a dinosaur fossil. The more realistic prospect is to take a live dinosaur you have lying around already: a bird. Modern birds are considered a surviving line of theropod dinosaurs, closely related to the T rex and velociraptor. (Just look at their feet: “theropod” means “beast-footed”.) By tinkering with how a bird embryo develops, you can silence some of its modern adaptations and let the older genetic instructions take over. Enterprising researchers have already  Having taught Philosophy for 46 years in three Universities—two State and one private—and never taught a Critical Thinking course one might have some questions about my choice of topic. My response is two-fold. First, there is a sense in which no matter what the topic of a particular course philosophy is always about critical thinking. One’s lectures are intended to model careful, reflective thought, sensitive to both the considerations favoring one’s views as well as the strongest objections. Second, because it is always going to be essential to use and define essential logical terminology.

Having taught Philosophy for 46 years in three Universities—two State and one private—and never taught a Critical Thinking course one might have some questions about my choice of topic. My response is two-fold. First, there is a sense in which no matter what the topic of a particular course philosophy is always about critical thinking. One’s lectures are intended to model careful, reflective thought, sensitive to both the considerations favoring one’s views as well as the strongest objections. Second, because it is always going to be essential to use and define essential logical terminology.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

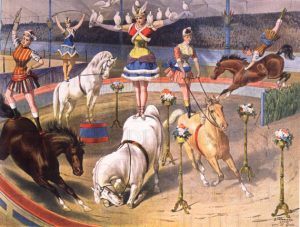

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus.

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus. Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood?

Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood?