by Max Sirak

Long before it ever even occurred to me to be a writer, I accidentally adopted the quirks and habits of one…

If one sits in my dining room, they can see it. There is literal writing on my wall. What once stood empty, with its deep red paint, is now plastered with Post-Its. My dining room features a Word-of-the-day wall. It took over five years to complete and started as many things do, by chance, during a drunken game of Scrabble.

Word-of-the-day-wall aside, there’s another writerly habit this column pertains to.

I can’t honestly tell you when I started my notes. Soon after college is all I’ve really got. Many moons ago I began highlighting passages in everything I read and typing them up. It’s a labor of love born in hopes of retention.

I learned at university that if I wanted to commit something to memory I needed to do more than simply read it. Remembering, for me, requires an action element. So, in the name of not forgetting everything I was learning from books, I started my notes.

Weighing in at damn near three-quarters of a million words, over 1,500 pages, and spanning 200 different entries, my notes are the closest thing to a life’s work I’ve got.

The best unforeseen consequence of my note taking is the overlap. Having spent so much time with my notes, I’ve got a good sense of what all is there. And, because of that, I’ve been able to notice some “odd” connections between apparently disparate sources. One such connection has given birth to a pet hypothesis…

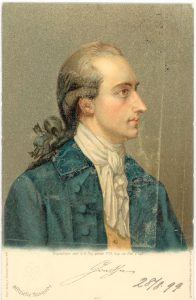

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a reincarnated 8th Century BCE Chinese monk and his seminal work, Faust, is a Zen treatise.

Before offering my proofs, we need to get on the same page.

Source Material and a Definition of Terms

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe finished publishing Faust in 1832. He started writing it 40 years prior. It’s a play in two parts about a man, Faust, who makes an infernal bargain with a devil, Mephistopheles. Since I don’t speak German, I’m working off of Stuart Atkins’s updated version of Bayard Taylor’s translation.

The ideas I’m using about Zen come from a series of lectures Rajneesh, or Osho, gave (More on him here). He, himself, was more of a talker than a writer. Luckily one of his disciples decided to collect, organize, and publish his guru’s thoughts in Zen: The Path of Paradox.

Lastly, there’s the concept of wu wei (More here). It comes from the Spring and Autumn period of China, the years between 771 and 476 BCE, and is a core concept in Taoism and Zen. Wu wei literally translates as non-doing. It’s a fast, effortless, seemingly automatic way of processing information and acting in the world. It’s what Danial Kahneman would call System 1 thinking. Both Malcolm Gladwell (Blink) and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Flow) have written books about it. So too has Edward Slingerland. And it’s from his book, Trying Not To Try, that I’m going to pull my quotes on wu wei today.

That covers all the terms and sources you’ll need to follow along as I show you how both Faust and Zen share the same goal, offer the same advice, caution against the same pitfall, and teach the same focal point.

Away We Goal!

Faust is widely considered a humanist work.

Humanism is a school of thought which puts, you guessed it, humans first. It’s not concerned with bowing to gods or worshiping the supernatural. If divinity is to be found anywhere it’s within, according to humanists.

Zen, it turns out, feels the same. “For Zen, man is the goal; man is the end unto himself. God is not something above humanity, God is something hidden within humanity.” (Osho)

The goal here is the same. Us.

And How!

Both Faust and Zen preach the same method of acting in the world and achieving our goals. The word, Zen, translates into English as, “How.” And that how isn’t maximal effort. It’s wu wei.

“Men err as long as they do strive.” (Goethe)

We have been taught to believe that the best way to achieve our goals is to reason about them carefully and strive consciously to reach them. Unfortunately, in many areas of life this is terrible advice. Many desirable states—happiness, attractiveness, spontaneity—are best pursued indirectly, and conscious thought and effortful striving can actually interfere with their attainment. (Slingerland)

“– Don’t seek, don’t search, don’t ask, don’t knock, don’t demand–relax. If you relax it comes. If you relax it is there.” (Osho)

Both Faust and Zen caution against forcing and favor wu wei.

“Take hold, then! Let reflection rest, / and plunge into the world with zest!” (Goethe)

Our excessive focus in the modern world on the power of conscious thought and the benefits of willpower and self-control causes us to overlook the pervasive importance of what might be called “body thinking”: tacit, fast and semiautomatic behavior that flows from the unconscious with little or not conscious interference. (Slingerland)

“We’re made for doing, not thinking.” (Slingerland)

Here Goethe speaks on the importance wu wei, or taking action instead not over-thinking.

Ideas Of Things Get In The Way

“My worthy friend, gray are all theories– / the verdant tree of Life alone is green.” (Goethe)

“Feeling is all in all, / name is but sound and smoke, / obscuring Heaven’s clear light.” (Goethe)

Theories are gray. They’re lifeless. They’re built of words. Words diffuse. They categorize and define. The sounds and syllables we use to describe certain things keep us at an intellectual arm’s length away. Or, put another way:

“The moment you enter into the world of words you start falling away from that which is. The more you enter into language, the farther you are away from existence. Language is a great falsification. It is not a bridge, it is not a communication–it is a barrier.” (Osho)

The Time Is Now

“Nor past nor future shades an hour like this, / the present moment only– / Is our bliss.” (Goethe)

“…Zen is neither interested in the past nor in the future. Its total interest is in the present.” (Osho)

Again both Faust and Zen align. The appropriate place to focus our energies and concerns aren’t in what’s been or what’s to come, but what is. Here. And Now.

Well?

Despite the distance, 2,300 years and 7,000 km, Faust and Zen share four points of philosophical overlap.

Both look to the same end – us.

Both preach the same path – wu wei.

Both warn against the same trap – thinking and the abstraction of words.

Both feature the same focus – the present moment.

All I’m saying is maybe – just maybe – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a reincarnated 8th Century BCE Chinese monk, who wrote a play in attempts to bring Zen and wu wei to 19th Century Western Europe….

Aren’t you glad I take notes?

***

Photos

- My World Wall

- Johann Wolfgang Goethe by Georg Oswald May – http://www.goethezeitportal.de/index.php?id=433

- Osho – By Preity.133 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21950314

Links

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goethe%27s_Faust

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rajneesh

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_wei

- http://bigthink.com/errors-we-live-by/kahnemans-mind-clarifying-biases

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zen

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanism