by Emrys Westacott

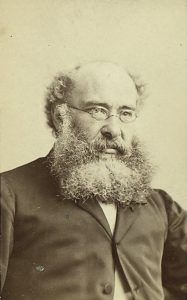

What do 21st century American college faculty and 19th century Church of England Clergyman have in common? A surprising amount. This is one reason I would heartily recommend the novels of Trollope, Austen, and others to my colleagues in academia.

What do 21st century American college faculty and 19th century Church of England Clergyman have in common? A surprising amount. This is one reason I would heartily recommend the novels of Trollope, Austen, and others to my colleagues in academia.

Clerics are interesting figures in a number of 19th century novels. Sometimes they are portrayed sympathetically, as is Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey; often, though, they are ridiculed, either gently, like Bishop Proudie in Barchester Towers, or scathingly, like Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice. But what should draw rueful smiles of recognition from academics today is not the personality types represented but their situations within a complicated, hierarchical system that dispenses enviable benefits to some and chronic frustration to others.

Extrapolating from such novels with a little imaginative license, we can form the following picture. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Church of England had about 11,500 “livings”–positions tied to particular parishes. These typically came with a house (the vicarage, the rectory), and an income, often quite modest. Such livings were usually dispensed by individuals or institutions that were major landowners in the parish. They provided life-long security and social respectability.

Under the primogeniture system of inheritance, the eldest son inherited the bulk of his father’s estate. This meant that younger sons of the gentry had to pursue some profession, and the respectable options for those who viewed trade as rather sordid were few: the military, the law, medicine, or the church. One of the important functions of the Church of England at that time was thus to provide socially acceptable employment to educated middle and upper-middle class men who lacked independent means.

Unfortunately, there were many more educated young men seeking positions in the church than there were “livings.” Supply exceeded demand. As late as 1830, about fifty percent of Oxbridge undergraduates intended to enter the church. Recently minted Ph.D.s seeking tenure-track positions will have no trouble relating to their situation. Read more »

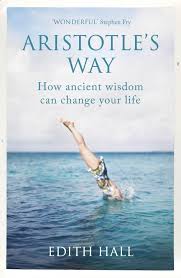

Edith Hall, a professor of classics at King’s College London, tried astrology, Buddhism, transcendental meditation, psychotropic drugs and spiritualism before discovering Aristotelianism as an undergraduate. Aristotle appealed to her because he rejected the idea of divine intervention in human affairs in favour of scientific explanations for life and its phenomena. He was also considerably less miserable than the average philosopher. For Aristotle, Hall explains, ‘the ultimate goal of human life is, simply, happiness’. And who doesn’t desire happiness? In the tradition of Alain de Botton, she has written a practical and enjoyable guide to Aristotle’s philosophy as a recipe for contentment in the modern world.

Edith Hall, a professor of classics at King’s College London, tried astrology, Buddhism, transcendental meditation, psychotropic drugs and spiritualism before discovering Aristotelianism as an undergraduate. Aristotle appealed to her because he rejected the idea of divine intervention in human affairs in favour of scientific explanations for life and its phenomena. He was also considerably less miserable than the average philosopher. For Aristotle, Hall explains, ‘the ultimate goal of human life is, simply, happiness’. And who doesn’t desire happiness? In the tradition of Alain de Botton, she has written a practical and enjoyable guide to Aristotle’s philosophy as a recipe for contentment in the modern world.

Most jobs that exist today might disappear within decades. As artificial intelligence outperforms humans in more and more tasks, it will replace humans in more and more jobs. Many new professions are likely to appear: virtual-world designers, for example. But such professions will probably require more creativity and flexibility, and it is unclear whether 40-year-old unemployed taxi drivers or insurance agents will be able to reinvent themselves as virtual-world designers (try to imagine a virtual world created by an insurance agent!). And even if the ex-insurance agent somehow makes the transition into a virtual-world designer, the pace of progress is such that within another decade he might have to reinvent himself yet again. The crucial problem isn’t creating new jobs. The crucial problem is creating new jobs that humans perform better than algorithms. Consequently, by 2050 a new class of people might emerge – the useless class. People who are not just unemployed, but unemployable. The same technology that renders humans useless might also make it feasible to feed and support the unemployable masses through some scheme of

Most jobs that exist today might disappear within decades. As artificial intelligence outperforms humans in more and more tasks, it will replace humans in more and more jobs. Many new professions are likely to appear: virtual-world designers, for example. But such professions will probably require more creativity and flexibility, and it is unclear whether 40-year-old unemployed taxi drivers or insurance agents will be able to reinvent themselves as virtual-world designers (try to imagine a virtual world created by an insurance agent!). And even if the ex-insurance agent somehow makes the transition into a virtual-world designer, the pace of progress is such that within another decade he might have to reinvent himself yet again. The crucial problem isn’t creating new jobs. The crucial problem is creating new jobs that humans perform better than algorithms. Consequently, by 2050 a new class of people might emerge – the useless class. People who are not just unemployed, but unemployable. The same technology that renders humans useless might also make it feasible to feed and support the unemployable masses through some scheme of  Benter and Coladonato watched as a software script filtered out the losing bets, one at a time, until there were 36 lines left on the screens. Thirty-five of their bets had correctly called the finishers in two of the races, qualifying for a consolation prize. And one wager had correctly predicted all nine horses.

Benter and Coladonato watched as a software script filtered out the losing bets, one at a time, until there were 36 lines left on the screens. Thirty-five of their bets had correctly called the finishers in two of the races, qualifying for a consolation prize. And one wager had correctly predicted all nine horses. Precisely how and when will our curiosity kill us? I bet you’re curious. A number of scientists and engineers fear that, once we build an artificial intelligence smarter than we are, a form of A.I. known as artificial general intelligence, doomsday may follow. Bill Gates and Tim Berners-Lee, the founder of the World Wide Web, recognize the promise of an A.G.I., a wish-granting genie rubbed up from our dreams, yet each has voiced grave concerns. Elon Musk warns against “summoning the demon,” envisaging “an immortal dictator from which we can never escape.” Stephen Hawking declared that an A.G.I. “could spell the end of the human race.” Such advisories aren’t new. In 1951, the year of the first rudimentary chess program and neural network, the A.I. pioneer Alan Turing predicted that machines would “outstrip our feeble powers” and “take control.” In 1965, Turing’s colleague Irving Good pointed out that brainy devices could design even brainier ones, ad infinitum: “Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.” It’s that last clause that has claws.

Precisely how and when will our curiosity kill us? I bet you’re curious. A number of scientists and engineers fear that, once we build an artificial intelligence smarter than we are, a form of A.I. known as artificial general intelligence, doomsday may follow. Bill Gates and Tim Berners-Lee, the founder of the World Wide Web, recognize the promise of an A.G.I., a wish-granting genie rubbed up from our dreams, yet each has voiced grave concerns. Elon Musk warns against “summoning the demon,” envisaging “an immortal dictator from which we can never escape.” Stephen Hawking declared that an A.G.I. “could spell the end of the human race.” Such advisories aren’t new. In 1951, the year of the first rudimentary chess program and neural network, the A.I. pioneer Alan Turing predicted that machines would “outstrip our feeble powers” and “take control.” In 1965, Turing’s colleague Irving Good pointed out that brainy devices could design even brainier ones, ad infinitum: “Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.” It’s that last clause that has claws.

At a company-wide town hall-style event in early April, Jeffrey Goldberg, the editor of The Atlantic, and his star writer, Ta-Nehisi Coates engaged in some candid public soul searching about how it is the venerable magazine, founded by abolitionists over 150 years ago, had hired (very briefly) a writer who advocated state-sanctioned hanging of women who abort pregnancies, and compared a small black child he encountered on a reporting trip to “a three-fifths scale Snoop Dogg” who gestured like a “primate.”

At a company-wide town hall-style event in early April, Jeffrey Goldberg, the editor of The Atlantic, and his star writer, Ta-Nehisi Coates engaged in some candid public soul searching about how it is the venerable magazine, founded by abolitionists over 150 years ago, had hired (very briefly) a writer who advocated state-sanctioned hanging of women who abort pregnancies, and compared a small black child he encountered on a reporting trip to “a three-fifths scale Snoop Dogg” who gestured like a “primate.” In its long philosophical history, beauty has taken detours. It has been derailed by technical wrangles and commandeered by authoritative proclamations of good taste. But perhaps now, we are only just starting to understand the exceptional nature of the experience it demarcates, how it works upon the body, alerts us to our susceptibility to the world and reminds us of our commitment to it. When the literary critic Elaine Scarry investigated beauty in the late 1990s, she noticed the ‘contract’ between the beautiful object and those who recognise it as such. Each, she notes, confers ‘the gift of life’, welcoming the other. It’s a cloying, rather vague expression, but there is something to this idea of a compact, the notion of a mutual realisation that unfolds between us and the object of our attention when we are engaged in judgments of beauty. Something rises to challenge our particular perceptual faculties, and we rise to meet it in turn.

In its long philosophical history, beauty has taken detours. It has been derailed by technical wrangles and commandeered by authoritative proclamations of good taste. But perhaps now, we are only just starting to understand the exceptional nature of the experience it demarcates, how it works upon the body, alerts us to our susceptibility to the world and reminds us of our commitment to it. When the literary critic Elaine Scarry investigated beauty in the late 1990s, she noticed the ‘contract’ between the beautiful object and those who recognise it as such. Each, she notes, confers ‘the gift of life’, welcoming the other. It’s a cloying, rather vague expression, but there is something to this idea of a compact, the notion of a mutual realisation that unfolds between us and the object of our attention when we are engaged in judgments of beauty. Something rises to challenge our particular perceptual faculties, and we rise to meet it in turn. Kanye west, a god in this time

Kanye west, a god in this time Among the boldest elements of Spinoza’s philosophy is his conception of God. The God of the Ethics is a far cry from the traditional, transcendent God of the Abrahamic religions. What Spinoza calls “God or Nature” lacks all of the psychological and ethical attributes of a providential deity. His God is not a personal agent endowed with will, understanding and emotions, capable of having preferences and making informed choices. Spinoza’s God does not formulate plans, issue commands, have expectations, or make judgments. Neither does God possess anything like moral character. God is not good or wise or just. What God is, for Spinoza, is Nature itself – the phrase he uses is Deus sive Natura – that is, the infinite, eternal and necessarily existing substance of the universe. God or Nature just is; and whatever else is, is “in” or a part of God or Nature. Put another way, there is only Nature and its power; and everything that happens, happens in and by Nature. There is nothing supernatural; there is nothing outside of or distinct from Nature and independent of its laws and operations.

Among the boldest elements of Spinoza’s philosophy is his conception of God. The God of the Ethics is a far cry from the traditional, transcendent God of the Abrahamic religions. What Spinoza calls “God or Nature” lacks all of the psychological and ethical attributes of a providential deity. His God is not a personal agent endowed with will, understanding and emotions, capable of having preferences and making informed choices. Spinoza’s God does not formulate plans, issue commands, have expectations, or make judgments. Neither does God possess anything like moral character. God is not good or wise or just. What God is, for Spinoza, is Nature itself – the phrase he uses is Deus sive Natura – that is, the infinite, eternal and necessarily existing substance of the universe. God or Nature just is; and whatever else is, is “in” or a part of God or Nature. Put another way, there is only Nature and its power; and everything that happens, happens in and by Nature. There is nothing supernatural; there is nothing outside of or distinct from Nature and independent of its laws and operations. For people with advanced cancer who are running out of options, many cancer centers now offer this hope: Have your tumor’s genome sequenced, and doctors will match you with a drug that targets its weak spot. But this booming area of cancer treatment has critics, who say its promise has been oversold. Last week, two prominent voices in the field faced off in a sometimes-tense debate on what’s often called precision oncology at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in Chicago, Illinois. Their dispute threw a splash of cold water on a meeting packed with sessions on genome-based cancer treatments.

For people with advanced cancer who are running out of options, many cancer centers now offer this hope: Have your tumor’s genome sequenced, and doctors will match you with a drug that targets its weak spot. But this booming area of cancer treatment has critics, who say its promise has been oversold. Last week, two prominent voices in the field faced off in a sometimes-tense debate on what’s often called precision oncology at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in Chicago, Illinois. Their dispute threw a splash of cold water on a meeting packed with sessions on genome-based cancer treatments.  A celebrated altercation between Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), the Florentine artist, and fellow sculptor Bartolommeo Bandinello (1493-1560) resulted in the latter exclaiming “Oh sta cheto, soddomitaccio.” [Shut up, you filthy sodomite!]. The accusation had merit in the legal sense at least since Cellini had indeed been accused of the crime of sodomy with at least one woman and several young men. The incident is oftentimes recalled in writings about the period as it provides a compelling illustration of the sexual appetites of the artists of the Renaissance.

A celebrated altercation between Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), the Florentine artist, and fellow sculptor Bartolommeo Bandinello (1493-1560) resulted in the latter exclaiming “Oh sta cheto, soddomitaccio.” [Shut up, you filthy sodomite!]. The accusation had merit in the legal sense at least since Cellini had indeed been accused of the crime of sodomy with at least one woman and several young men. The incident is oftentimes recalled in writings about the period as it provides a compelling illustration of the sexual appetites of the artists of the Renaissance.

What do 21st century American college faculty and 19th century Church of England Clergyman have in common? A surprising amount. This is one reason I would heartily recommend the novels of Trollope, Austen, and others to my colleagues in academia.

What do 21st century American college faculty and 19th century Church of England Clergyman have in common? A surprising amount. This is one reason I would heartily recommend the novels of Trollope, Austen, and others to my colleagues in academia.

Since 2014, various student societies at the University of Edinburgh have but on musical performances commemorating the first world war. This article takes a look at one performance in particular. The content is neither highly original nor particularly radical; others have written more insightful and more sophisticated pieces. It constitutes merely an attempt to formulate and to clarify what is problematic with these particular performances, thereby hoping to understand something about the greater memorial tradition in the United Kingdom. In other words, by examining how a nationalistic, martial and oppressive Erinnerungskultur is reproduced in an amateur to semi-professional context – be it deliberately or not -, we may see how these values become normalised and why it matters that this takes place in this particular context.

Since 2014, various student societies at the University of Edinburgh have but on musical performances commemorating the first world war. This article takes a look at one performance in particular. The content is neither highly original nor particularly radical; others have written more insightful and more sophisticated pieces. It constitutes merely an attempt to formulate and to clarify what is problematic with these particular performances, thereby hoping to understand something about the greater memorial tradition in the United Kingdom. In other words, by examining how a nationalistic, martial and oppressive Erinnerungskultur is reproduced in an amateur to semi-professional context – be it deliberately or not -, we may see how these values become normalised and why it matters that this takes place in this particular context. When my partner and I were expecting our first child, I remained obstinately distant from all parenting books. I had adapted, and taken to heart, Rainer Rilke’s advice to Franz Kappus about avoiding introductions to great works of art, and reckoning that, in the poet’s words, “such things are either partisan views, petrified and grown senseless in their lifeless induration, or they are clever quibblings in which today one view wins and tomorrow the opposite.” Rilke’s point seems to be that introductions do more to obscure our ability to reach the work of art than elucidate it. Since a child is, among other things, a living, breathing work of art, it took very little for me to translate the great poet’s advice to the work of child-rearing. Surely no book would truly help me approach a task as infinitely arduous and dizzyingly beautiful as bringing a human being into the world.

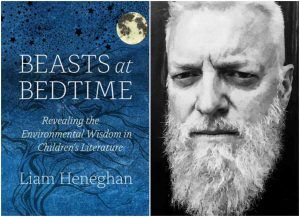

When my partner and I were expecting our first child, I remained obstinately distant from all parenting books. I had adapted, and taken to heart, Rainer Rilke’s advice to Franz Kappus about avoiding introductions to great works of art, and reckoning that, in the poet’s words, “such things are either partisan views, petrified and grown senseless in their lifeless induration, or they are clever quibblings in which today one view wins and tomorrow the opposite.” Rilke’s point seems to be that introductions do more to obscure our ability to reach the work of art than elucidate it. Since a child is, among other things, a living, breathing work of art, it took very little for me to translate the great poet’s advice to the work of child-rearing. Surely no book would truly help me approach a task as infinitely arduous and dizzyingly beautiful as bringing a human being into the world.