by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

My earliest encounter with English poetry drew a subliminal connection with the Irish poets, a connection I could not easily pinpoint as a student of literature in Lahore, Pakistan, but one that re-emerged with striking clarity on my first visit to Ireland. Seeing fragments of poetry adorning hotel walls, ceilings of pubs and elevators in Dublin, I was reminded of verses of Urdu poetry on the television screen, and verses, (often sentimental or humorous ones) painted on trucks and rickshaws back when I was growing up in Pakistan. Poetry in Urdu as well as the other (“provincial”) languages— written, recited, repeated as part of ordinary speech— is a dominant part of Pakistani culture as it is of Ireland, though Pakistan has yet to produce a Nobel laureate in Literature, as opposed to Ireland whose literary laurels, both in quantity and level of prestige, are an embarrassment of riches.

While in Dublin, I came across references to the Irish movement of Independence multiple times a day; reminders of freedom from British rule punctuate the city as landmarks and shapes its psyche. The historical moment of gaining sovereignty is key not only as a constantly (and proudly) visited chapter in mainstream culture, but also as a moment that hearkens back to the nation’s great literary figures who played a pivotal role in achieving independence— a scenario all too familiar to someone from Pakistan, a country whose nationhood was first suggested by a poet. The timeline of the struggle for independence from British rule is the same (late 19th—early 20th century) for the Indo-Pak subcontinent and Ireland, as is the fact that the movement included a milieu of writers among the leaders. It is the partition of Pakistan from India and the defining and defending of a new identity that Pakistan has in common with Ireland, the “anti-partition” camp in the larger political conversation notwithstanding.

David Aberbach, in his analysis of some of the most influential poets who wrote against British Imperialism, says: “The British empire set off an explosion of poetry, in English and native languages, particularly in India, Africa and the Middle East. This poetry – largely neglected in the scholarship on nationalism – was often revolutionary both aesthetically and politically, expressing a spirit of cultural independence. Attacks on England and the empire are common not just in native colonial poetry but also in poetry of the British isles.” Some of the poets included in this work are: Tagore of India, Yeats of Ireland, and Iqbal of Pakistan.

Besides the historical and political role that poetry has played in the foundation of the two countries, I have discovered quite a few other aspects having to do with aesthetics that offer clues to why, as a diaspora poet in the US, I have found myself gravitating to the same Irish poets I took an immediate liking to in my young days— a connection reaffirmed in recent years by the Kashmiri-American poet Rafiq Kathwari (winner of the Patrick Kavanaugh Prize who has a home in Dublin as well as New York), and remarkably reinforced by the Irish poet and editor Peter O’Neill— thanks to whom I have been able to engage afresh with Irish poetry in a fuller, deeper and clearer way.

Peter’s own work is infused with a powerful sense of history, not only in the wider context of literary and cultural tradition, geopolitics, and aesthetic modes, but the local history of his coastal hometown of Skerries, a suburb of Dublin, where he moved after spending many years in France. His deep engagement with history entails everything from his interest in sites of antiquity in Skerries, its history over the centuries, and its contemporary literary scene. In a blog post, Peter writes: “I don’t know what it is about this particular part of the world, but since I moved here with my family in 2009 I have been writing like a fool.” Here are some lines from his poem “The Local.”

The Local

Under the suspended lamps like manifold moons

the all-encompassing locality hits you like the sharp slap

of an unintentional elbow to the face.

Here,

conversations shift like the breeze.

Once opened,

rows of solid entities

may cause the further assessment

of the transience of all matter.

Fiddle and banjo pull to the strains of a singular life.

And the sole measure of certitude are the pints,

on that everyone is agreed.

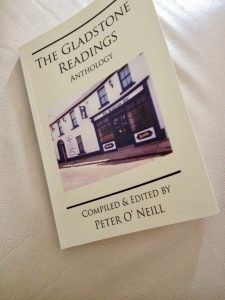

Peter’s first book, Sker (Lapwing Press) is named after Skerries— he has been curating a reading series at the Gladstone Inn in Skerries, a series that has brought together many illustrious poets and generated a wonderful anthology edited by Peter himself. It was my conversation with Peter at the Gladstone Inn (where he had invited me to share poems), and reading his poems as well as the selections in The Gladstone Inn Anthology that have acted as a catalyst in my understanding of what drew me to Irish poetry in my earliest experience as a reader and writer. The commonalities between the Irish and Pakistani culture and history as pertaining to poetry are mindboggling, considering the absence of geographic and cultural proximity.

Among the instances of stylistic and thematic parallels I have come across in the anthology, I note a hunger for identity which is expressed through the love/praise of the land, its legends, its folklore, its ancient history, landscape, weather, minutia of everyday life, often the grand and the exquisite juxtaposed with the banal; I also see concerns of religion as a binding or a severing force for culture—nuances of faith and spirituality being at odds with the tribal/exclusivist aspects of religion, the fine line which only the poets can draw in a way that is powerful enough to make an impact: needless to say the distinction is of urgent importance in today’s political climate. Here are some beautiful lines by Peter O’Neill:

“The clocks on the shelves announce tedium with a tick

and all manner of danger with a tock.

We are always, despite ourselves, in the realm of the divine.”

Some of the gestures that are markedly aware of the collective may be labeled anti-modern or nationalistic, but in my view, a post-colonial search for (and crafting of) cultural identity, especially if approached in a richly varied, deeply aware manner is quite likely to make a promising future.

What I find most appealing about this anthology, stylistically speaking, is its bold lyricism, untouched by self-consciousness and anxiety. I read Yeats’s book of Irish folk and fairy tales after reading the Gladstone Inn Anthology and wondered if the deep-seated conviction in the imagination makes for the stunningly powerful and confident lyricism of these poems; does it liberate the spirit so that the confines of craft come across as elegantly seamless? Is it this sense of empowerment that stems from owning the imagination not just as an individual writer but as a culture, a force that fine-tunes intuition and enhances the faculty for spontaneity and ease with language?

Here is one of my favorite poems by Peter O’Neill:

Tenth Wedding Anniversary

For Alessia

Salvador Dali, Federico Garcia Lorca, and Luis Bunuel

Have just left Port Lligat, they were last seen entering

Porto Palma on a Steinway pulled by a couple of albino

Donkey, who in turn were being led by two Catalan priests.

The sea on which they sailed was the colour of black flint,

And upon the beach a wedding ceremony was being held;

The groom was dressed as the bride, the bride the groom.

She held in her left hand a statue signifying the origin of all patriarchs.

The groom, meanwhile, held a scissors,

And the President of the Municipal Association

Was inviting him to cut the ribbon of all ribbons.

When he did, the seas tides convulsed

And became pure Cannonau, which was later served

Up to them by the local fishermen in clam shells served with garlic.