Evelyn Lamb in Smithsonian:

April is both National Poetry Month and Mathematics and Statistics Awareness Month, so a few years ago science writer Stephen Ornes dubbed it Math Poetry Month. If the words “math” and “poetry” don’t intuitively make sense to you as a pair, poet and mathematician JoAnne Growney’s blog Intersections—Poetry with Mathematics is a perfect place to start expanding your math-poetic horizons. The blog includes a broad range of poems with mathematical themes or built using mathematical rules. Take “Geometry,” by former U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove:

I prove a theorem and the house expands:

the windows jerk free to hover near the ceiling,

the ceiling floats away with a sigh.

—from “Geometry” by Rita Dove

…Growney grew up wanting to be a writer. “I read Little Women as a girl, and maybe it was partly the name connection, but I thought that I wanted to be a writer like Jo.” She was also good at math, though, and ended up with a scholarship to study it in college. She stuck with it and earned her Ph.D. in 1970 at the University of Oklahoma. During her career as a math professor, her interest in writing continued. She took poetry classes at a nearby college when she could, discovered the math poetry anthology Against Infinity while doing a sabbatical project about mathematics and the arts, and started to see her feelings about mathematics echoed in poetry. Mathematics and poetry, Growney says, are both “formats that can convey multiple meanings.” In mathematics, a single object or idea might take different forms. A quadratic equation, for example, can be understood in terms of its algebraic expression, perhaps y=x2+3x-7, or in terms of its graph, a parabola. Henri Poincaré, a French polymath who laid the foundations of two different fields of mathematics in the early 1900s, described mathematics as “the art of giving the same name to different things.”

More here.

Neuroscientist Michael Heneka knows that radical ideas require convincing data. In 2010, very few colleagues shared his belief that the brain’s immune system has a crucial role in dementia. So in May of that year, when a batch of new results provided the strongest evidence he had yet seen for his theory, he wanted to be excited, but instead felt nervous. He and his team had eliminated a key inflammation gene from a strain of mouse that usually develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The modified mice seemed perfectly healthy. They sailed through memory tests and showed barely a sign of the sticky protein plaques that are a hallmark of the disease. Yet Heneka knew that his colleagues would consider the results too good to be true.

Neuroscientist Michael Heneka knows that radical ideas require convincing data. In 2010, very few colleagues shared his belief that the brain’s immune system has a crucial role in dementia. So in May of that year, when a batch of new results provided the strongest evidence he had yet seen for his theory, he wanted to be excited, but instead felt nervous. He and his team had eliminated a key inflammation gene from a strain of mouse that usually develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The modified mice seemed perfectly healthy. They sailed through memory tests and showed barely a sign of the sticky protein plaques that are a hallmark of the disease. Yet Heneka knew that his colleagues would consider the results too good to be true. Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!”

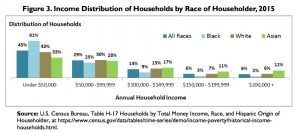

Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!” Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”

Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”