Tom Bartlett in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

You can order Gnome Chomsky, the Garden Noam for $195, plus shipping. A “What Would Noam Do?” mug can be yours for $15. “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously,” an oft-repeated demonstration of how words can be simultaneously grammatical and nonsensical, is available both as a bumper sticker and an iPhone case. Noam Chomsky is souvenir-level famous.

You can order Gnome Chomsky, the Garden Noam for $195, plus shipping. A “What Would Noam Do?” mug can be yours for $15. “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously,” an oft-repeated demonstration of how words can be simultaneously grammatical and nonsensical, is available both as a bumper sticker and an iPhone case. Noam Chomsky is souvenir-level famous.

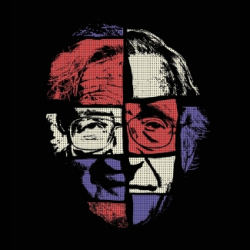

That’s what happens when you are “arguably the most important intellectual alive today,” a line from a 1979 New York Times book review that’s been recycled ever since as shorthand for a hard-to-summarize man. The same book review, written by Paul Robinson, a Stanford historian, goes on to outline what he calls “the Chomsky problem,” that is, “the problem of an opinionated historian inhabiting the same skin as the brilliant and subtle linguist.” There is Noam Chomsky, father of modern linguistics, whose theory of Universal Grammar seeks to explain human language. And there is Noam Chomsky, the political activist and writer, who remains among the most unrelenting critics of American military action. In his new book, Tom Wolfe takes a crack at explaining that bifurcated persona. (Yes, that Tom Wolfe — the Bonfire of the Vanities, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test guy.). He describes the divide with patented Wolfeian exuberance: “Chomsky’s politics enhanced his reputation as a great linguist, and his reputation as a great linguist enhanced his reputation as a political solon, and his reputation as a political solon inflated his reputation from great linguist to all-around genius, and the genius inflated the solon into a veritable Voltaire, and the veritable Voltaire inflated the genius of all geniuses into a philosophical giant … Noam Chomsky.”

Once fully inflated, Wolfe proceeds to stick a pin in him. The Kingdom of Speech (Little, Brown and Company) is one of two new books that offer sour portraits of the soft-spoken, if not always mild-mannered, emeritus professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The other, Decoding Chomsky: Science and Revolutionary Politics (Yale University Press), by Chris Knight, was a decade in the making and may be the most in-depth meditation on “the Chomsky problem” ever published. Like Wolfe, Knight first consecrates Chomsky, noting that, by one measure, he is the eighth-most-cited thinker in the humanities — hot on the heels of fellow one-namers like Freud and Plato — before setting fire to the shrine.

Is this any way to treat arguably the most important intellectual alive?

More here.