by S. Abbas Raza

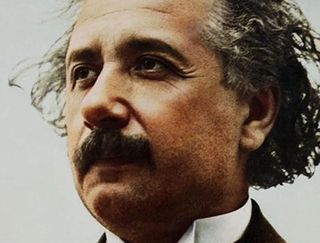

In November of 1915, Albert Einstein published what would come to be known as his theory of general relativity. Ten years ago, I wrote as simple an explanation as I could of some of the more salient aspects of that theory, here at 3 Quarks Daily. I am republishing that article below.

In November of 1915, Albert Einstein published what would come to be known as his theory of general relativity. Ten years ago, I wrote as simple an explanation as I could of some of the more salient aspects of that theory, here at 3 Quarks Daily. I am republishing that article below.

General Relativity, Very Plainly

[NOTE: Since I wrote and published this essay last night, I have received a private email from Sean Carroll, who is the author of an excellent book on general relativity, as well as a comment on this post from Daryl McCullough, both pointing out the same error I made: I had said, as do many physics textbooks, that special relativity applies only to unaccelerated inertial frames, while general relativity applies to accelerated frames as well. This is not really true, and I am very grateful to both of them for pointing this out. With his permission, I have added Sean's email to me as a comment to this post, and I have corrected the error by removing the offending sentences.]

In June of this year, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the publication of Einstein's original paper on special relativity, I wrote a Monday Musing column in which I attempted to explain some of the more salient aspects of that theory. In a comment on that post, Andrew wrote: “I loved the explanation. I hope you don't wait until the anniversary of general relativity to write a short essay that will plainly explain that theory.” Thanks, Andrew. The rest of you must now pay the price for Andrew's flattery: I will attempt a brief, intuitive explanation of some of the well-known results of general relativity today. Before I do that, however, a caveat: the mathematics of general relativity is very advanced and well beyond my own rather basic knowledge. Indeed, Einstein himself needed help from professional mathematicians in formulating some of it, and well after general relativity was published (in 1915) some of the greatest mathematicians of the twentieth century (such as Kurt Gödel) continued to work on its mathematics, clarifying and providing stronger foundations for it. What this means is, my explication here will essentially not be mathematical, which it was in the case of special relativity. Instead, I want to use some of the concepts I introduced in explaining special relativity, and extend some of the intuitions gathered there, just as Einstein himself did in coming up with the general theory. Though my aims are more modest this time, I strongly urge you to read and understand the column on special relativity before you read the rest of this column. The SR column can be found here.

Before anything else, I would like to just make clear some basics like what acceleration is: it is a change in velocity. What is velocity? Velocity is a vector, which means that it is a quantity that has a direction associated with it. The other thing (besides direction) that specifies a velocity is speed. I hope we all know what speed is. So, there are two ways that the velocity of an object can change: 1) change in the object's speed, and 2) change in the object's direction of motion. These are the two ways that an object can accelerate. (In math, deceleration is just negative acceleration.) This means that an object whose speed is increasing or decreasing is said to be accelerating, but so is an object traveling in a circle with constant speed, for example, because its direction (the other aspect of velocity) is changing at any given instant.

Get ready because I'm just going to give it to you straight: the fundamental insight of GR is that acceleration is indistinguishable from gravity. (Technically, this is only true locally, as physicists would say, but we won't get into that here.) Out of this amazing notion come various aspects of GR that most of us have probably heard about: that gravity bends light; that the stronger gravity is, the more time slows down; that space is curved. The rest of this essay will give somewhat simplified explanations of how this is so.

Continue reading “General Relativity, Very Plainly”

Martin Filler at the NYRB: