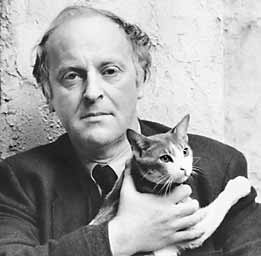

Joseph Brodsky (who would've been 75 today) in the NYRB:

No matter how daring or cautious you may choose to be, in the course of your life you are bound to come into direct physical contact with what’s known as Evil. I mean here not a property of the gothic novel but, to say the least, a palpable social reality that you in no way can control. No amount of good nature or cunning calculations will prevent this encounter. In fact, the more calculating, the more cautious you are, the greater is the likelihood of this rendezvous, the harder its impact. Such is the structure of life that what we regard as Evil is capable of a fairly ubiquitous presence if only because it tends to appear in the guise of good. You never see it crossing your threshold announcing itself: “Hi, I’m Evil!” That, of course, indicates its secondary nature, but the comfort one may derive from this observation gets dulled by its frequency.

A prudent thing to do, therefore, would be to subject your notions of good to the closest possible scrutiny, to go, so to speak, through your entire wardrobe checking which of your clothes may fit a stranger. That, of course, may turn into a full-time occupation, and well it should. You’ll be surprised how many things you considered your own and good can easily fit, without much adjustment, your enemy. You may even start to wonder whether he is not your mirror image, for the most interesting thing about Evil is that it is wholly human. To put it mildly, nothing can be turned and worn inside out with greater ease than one’s notion of social justice, public conscience, a better future, etc. One of the surest signs of danger here is the number of those who share your views, not so much because unanimity has a knack of degenerating into uniformity as because of the probability—implicit in great numbers—that noble sentiment is being faked.

By the same token, the surest defense against Evil is extreme individualism, originality of thinking, whimsicality, even—if you will—eccentricity. That is, something that can’t be feigned, faked, imitated; something even a seasoned impostor couldn’t be happy with. Something, in other words, that can’t be shared, like your own skin—not even by a minority. Evil is a sucker for solidity. It always goes for big numbers, for confident granite, for ideological purity, for drilled armies and balanced sheets. Its proclivity for such things has to do presumably with its innate insecurity, but this realization, again, is of small comfort when Evil triumphs.

Which it does: in so many parts of the world and inside ourselves. Given its volume and intensity, given, especially, the fatigue of those who oppose it, Evil today may be regarded not as an ethical category but as a physical phenomenon no longer measured in particles but mapped geographically. Therefore the reason I am talking to you about all this has nothing to do with your being young, fresh, and facing a clean slate. No, the slate is dark with dirt and it’s hard to believe in either your ability or your will to clean it. The purpose of my talk is simply to suggest to you a mode of resistance which may come in handy to you one day; a mode that may help you to emerge from the encounter with Evil perhaps less soiled if not necessarily more triumphant than your precursors. What I have in mind, of course, is the famous business of turning the other cheek.

More here.