Month: January 2014

Dedh Ishqiya and Urdu in India Today

Shoaib Daniyal in NY NewsYaps:

In a riotously funny scene from recently released comic thriller Dedh Ishqiya, Jaan Mohammad (played by Vijay Raaz) aggressively threatens a very drunk Khalujaan (Naseeruddin Shah) to leave town so that he can win the hand of the beautiful Begum Para (Madhuri Dixit). In a twist typical of the film, fist fights and gun brandishing suddenly give way to poetry, as Khalujaan picks up the word “wādā” (promise) used by Jaan and starts taunting him using asher. A gangster by profession and somewhat removed from the world of poetry, Jaan retorts as best he can by racking his brains and coming up with the only sher he knows on “wādā. This change of playing field from violence to poetry, though, can only end badly for Jaan. His verse induces derisive laughter from Khalujaan who then points out that Jaan’s original sher spoke of “bādā” (wine) and not “wādā” at all. Jaan just confused the two rhyming words.

It is credit to the competence of director Abhishek Chaubey that the Bombay heater I was in found the wordplay funny and laughed along with Khalu, in spite of the fact that very few would have been able to point out Jaan’s mistake themselves. Anupama Chopra, movie critic for the Hindustan Times, though, might have empathised more with Jaan and his struggles with High Urdu. While generally praising the film, she did end her review with one small regret: “I also struggled with the Urdu,” she said.“It was melodious but I wish I understood more of it.”

This frank admission, and the fact that Dedh Ishqiya is the only Bollywood film I’ve ever seen with English subtitles, contains within it some stark irony for an industry which, it could be said, was born into Urdu.

More here.

Pakistan’s War – Part II

by Ahmed Humayun

(This is the second post on Pakistan's struggle against militancy. Part I is here).

To prevail against an insurrection, a state must fight on many fronts. It must construct a comprehensive military and political strategy, strengthen its institutional capacity to fight an internal war, and mobilize public support for a protracted struggle. Above all, an insurgency is a contest between the state and its challengers over legitimacy and credibility. In this clash of narratives, the state must persuade the population that its actions are those of a representative, duly constituted government attempting to restore its control even as the rebels repudiate the fundamental legitimacy of the state.

So far in Pakistan the militant groups are winning the war of narrative. As I wrote last time, the Pakistani Taliban is by no means a monolith but its different factions do come together around a clear strategic story. Insurgent propaganda states that the rebellion's goal is to replace an illegitimate, un-Islamic government subservient to Washington with an Islamic state. Their war is defensive—for Islam and against America. The state, on the other hand, speaks in contradictory voices. Some say that the state must fight until the rebels lay down their arms, forswear the use of violence, and respect the rule of law, while others insist on immediate, unconditional negotiations. The truth is that ending the turmoil within Pakistan requires some adroit combination of fighting and talking—but only if they are aspects of an integrated strategy that has as its aim the restoration of state control and that realistically accounts for the ambitions of the rebels, which are revolutionary, and which they have pursued from the mountains in the tribal areas to major urban centers across the heartland.

Yet advocates of negotiation —including leading politicians, retired generals, and influential pundits—blame the state and its alliance with Washington rather than the militants for fomenting the violence. As a result it is widely believed in Pakistan that the war against militancy has been foisted on the country by the United States; that insurgent violence is merely retaliation for Pakistani military aggression and American drone strikes in the tribal areas; and that conflict will cease when these operations end. The result is that formula recited by many: ‘This is not our war.' This dominant narrative has had a negative effect on the legitimacy of the state in the eyes of the public, created demoralization in the country's army and police forces, and emboldened the insurgents.

Monday Poem

What God Says

I place before you a bowl of evidence

but will never make you eat

Chance is what you’re up against,

and the only is of me you’ll meet

You can pray until your tongue expires

and never know my heart’s desire

I roll the future out mysteriously,

you trace my trail of crumbs through mires

You profusely write of who I am

as if I were like you a man

You cannot know the I of me

unless you crack the I of thee

In the light and in the gloom

I beat a drum and hum your tune

.

by Jim Culleny

1/24/14

Kelvin, Rutherford, and the Age of the Earth: I, The Myth

by Paul Braterman

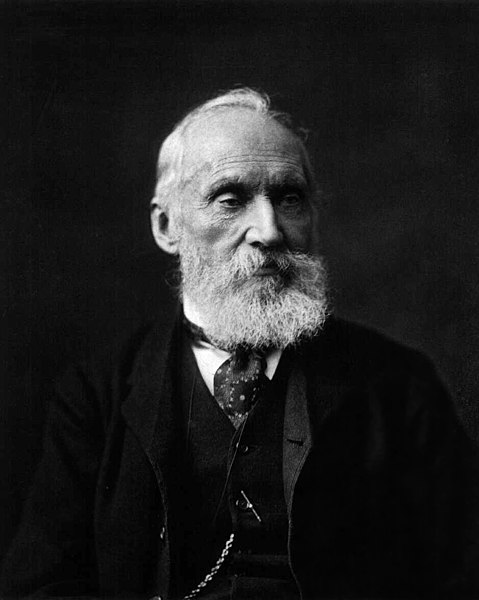

Lord Kelvin (Smithsoinian Instituion Libraries collection)

Kelvin calculated that the Earth was probably around 24 million years old, from how fast it is cooling. Rutherford believed that Kelvin’s calculation was wrong because of the heat generated by radioactivity. Kelvin was wrong, but so was Rutherford. The Earth is indeed many times older than Kelvin had calculated, but for completely different reasons, and the heat generated by radioactive decay has nothing to do with it.

Disclosure: in my introduction to the Scientific American Classic, Determining the Age of the Earth, and elsewhere, I have like many other authors repeated Rutherford’s argument with approval, without paying attention to Rutherford’s own warning that qualitative is but poor quantitative, and without bothering to check whether the amount of heat generated by radioactivity is enough to do the job. He thought it was but we now know it isn’t. It was only when chatting online (about one of the few claims in the creationist literature that is even worth discussing) that I discovered the error of my ways.

On the face of it, things could not be plainer. Kelvin had calculated the age of the Earth from how fast heat was flowing through its surface layers. An initially red hot body would have started losing heat very quickly, but over geological time the process would have slowed, as a relatively cool outer crust formed. His latest and most confident answer, reached in 1897 after more than 50 years of study, was in the range of around 24 million years.[1]

Perceptions

Pleasure of Fragments/Pleasure of Wholes

by Mara Jebsen

Rodin was famous for his fragments, and, in his era, hotly defended the choice to sculpt just a hand, or a torso, or a foot melting back into its original rock. The character Bernard, in Virginia Woolf's experimental “The Waves” seems to have revealed something about Woolf's thoughts on the unfinished, as he goes about talking, story-spinning, and worrying about the way life seems to accumulate more than culminate, so that all we get is phrases, bits. While coherence–in story, in body–provides a comforting pleasure for the audience, artists who know how to make wholes sometimes get weary of the falseness that an orderly whole brings with it–and take a pleasure in the fragment, the seemingly unfinished, strangely perfect, part.

I know, from my work as a writing teacher, that almost any student can produce a promising fragment, but very few can manage a coherent whole–in terms of idea, or story– without a great deal of coaxing, insistance, and endless re-writing. The work of a beginner is to complete the fragment. But perhaps the work of a master is to let the fragment be.

As a beginning storyteller myself, I find that whole tales are elusive, and the images arrive like little shards of a broken mirror. What to make of them–that's the hard part. What follows is the first piece of a tiny “novel” that is all pieces, inspired by a Sufi tale I heard three years ago, and subsequently garbled in my mind. In it, a man is visited by three different messengers, all strangers, each of whom require that he leap violently away from the life he is leading, and begin again. In the third phase of the man's life, he begins to show signs of spiritual enlightenment, and he ends as a mystic. The story, for some reason, made dozens of images–partial ones stuck in angled mirror-shards–arrive in my head for two years. In my version, the eventual mystic is a girl. She is young, wealthy, blank.

Poem

TODAY WINDY THEN SHOWERS

Gold-plated heels

On heart-shaped leaves

Calf-highs below

Slim band of flesh

Flirty pleats creased

Above naked knees

Ruby clutch releases

Jangling of keys

Wanton cornrows unbraided

In last night's storm

In last night's storm

Wanton cornrows unbraided

Jangling of Keys

Ruby Clutch releases

Above naked knees

Flirty Pleats creased

Slim band of flesh

Below calf-highs

On heart-shaped leaves

Gold-plated heels

By Rafiq Kathwari

CATSPEAK

by Brooks Riley

Days of Glory

by Lisa Lieberman

I used to teach a course on French colonialism, from the Napoleonic Wars of the early nineteenth century through the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962). On the first day of class, we read Jean de Brunhoff's classic children's book, The Story of Babar. De Brunhoff's story can be viewed as “an allegory of French colonization, as seen by the complacent colonizers,” to quote New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik:

the naked African natives, represented by the “good” elephants, are brought to the imperial capital, acculturated, and then sent back to their homeland on a civilizing mission. The elephants that have assimilated to the ways of the metropolis dominate those which have not. The true condition of the animals—to be naked, on all fours, in the jungle—is made shameful to them, while to become an imitation human, dressed and upright, is to be given the right to rule.

Gopnik, I should add, distances himself from such political readings of the book. He sees Babar as both a manifestation of the French national character, circa 1930 (when de Brunhoff's wife first came up with the tale, which she told to the couple's young sons as a bedtime story) and a gentle parody of it, “an affectionate, closeup caricature of an idealized French society.”

I remember enjoying the book as a child, and I've read it to my own children, but for all its charm, I'm not willing to let Babar off the hook quite so easily. The business of the civilizing mission—the “native” elephants adopting the values and behavior of the humans who inhabit the city—is cringe-inducing enough, but what really troubles me is de Brunhoff's ending. Here the fantasies of French nativists come true. The elephants come and immediately assimilate, recognizing the superiority of the mother country, hang around long enough to entertain their hosts with anecdotes about their exotic origins, and then they go home.

Blindspots and A Democratic Euromaidan: On The Protests in the Ukraine

First, Volodymyr Ishchenko in Eurozine:

[T]he open letter signed by established academics, many of whom are mainly politically progressive, ignores the extent of far-right involvement in the Ukrainian protests. One of the major forces at Euromaidan is the far-right xenophobic party “Svoboda” (“Freedom”). They are dominant among the volunteering guards of the protest camp and are the vanguard of the most radical street actions, such as the occupation of the administrative buildings in central Kyiv. Before 2004, “Svoboda” was known as the Social-National Party of Ukraine and used the Nazi “Wolfsangel” symbol. The party leader Oleh Tiahnybok is still known for his anti-Semitic speech. Even after re-branding, Svoboda has been seeking cooperation with neo-Nazi and neo-fascist European parties such as the NDP in Germany and Forza nuova in Italy. Its rank-and-file militants are frequently involved in street violence and hate crimes against migrants and political opponents.

At Euromaidan, particularly, far-right attackers assaulted a left-wing student group attempting to bring social-economic and gender equality issues to the protest. Several days later, a far-right mob beat and seriously injured two trade union activists, accusing them of being “communists”. Slogans previously connected with far-right subculture, such as “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!”, “Glory to the nation! Death to enemies!”, “Ukraine above all!” (an adaptation of Deutschland über alles) have now become mainstream among the protestors.

More here. Volodymyr Kulyk responds:

In his blinding opposition to both nationalism and capitalism, Ishchenko lumps together two very different matters: the role of rightwing radicals in Euromaidan and the role of these protests in Ukraine's choice of future. He is right that the radical nationalists do not share the protests' original goal of bringing Ukraine closer to the European Union and harm the democratic movement with their divisive slogans and their attacks on ideological opponents within the movement. However, he is wrong in arguing that such slogans and attacks invalidate the protests' value as a manifestation of the democratic and European aspirations of the Ukrainian people.

Although radical nationalists such as the Svoboda (Freedom) party and the less well-known organization called Rightwing Sector do not by any means constitute the majority of protesters, they are indeed rather prominent due to their vocal and visually striking behaviour.

More here. Also see this piece by Alex Motyl.

The Left in India has lost touch with the instincts and knowledges on which it has traditionally based its theoretical and practical positions

Akeel Bilgrami in The Indian Express:

In the United States, where I am domiciled, very little that makes for fundamental change in people’s lives gets onto the agenda of what is on offer in electoral politics. The two parties in the political arena merely represent competing “power elites”, to use a term of C. Wright Mills, and any basic opposition to this consensus of elite (mostly corporate) power has always come not from policies creatively formulated in the corridors of power by elected leaders, but from movements on the street which have occasionally forced elected leaders to make important changes — such as the labour movements of the 1930s or the civil rights and women’s movements of a few decades later. India, by contrast, has the distinct advantage of having a multiparty political system and so, even if there is a consensus among two of the major parties, there are others which may present alternatives outside the consensus, so long as the people are cognitively prepared to see the merit in the alternatives and their minds are not entirely shaped by the ideologies and ways of thinking underlying the consensus itself.

That brings us to the second question. The outcome of the 2004 elections in India is a telling example of what is at issue here. It is known that in the months prior to that election, pundits in the print and televised media were cheerleading for the utterly illusory claims of an emergent India under the policies that the government had been pursuing. Yet the government was defeated. In a sense, then, the mass of our people were saved by a combination of their illiteracy (the illusion of “India Shining” afflicted only the literate metropolitan classes who were cognitively fed by the media) and their knowledge of the causes of their own impoverished conditions, thereby revealing that everyday political knowledge and media literacy are by no means the same thing.

More here.

Open Letter from Ukrainian Writer Yuri Andrukhovych

From New Eastern Europe:

Dear Friends,

These days I receive from you lots of inquiries to describe the current situation in Kyiv and overall in Ukraine, express my opinion on what is happening and formulate my vision of at least the nearest future. Since I am simply physically unable to respond separately to each of your publications with an extended analytical essay, I have decided to prepare this brief statement which each of you can use in accordance with your needs. The most important things I must tell you are as follows.

During the less than four years of its rule, Viktor Yanukovych’s regime has brought the country and the society to the utter limit of tensions. Even worse, it has boxed itself into a no-exit situation where it must hold on to power forever – by any means necessary. Otherwise it would have to face criminal justice in its full severity. The scale of what has been stolen and usurped exceeds all imagination of what human avarice is capable.

The only answer this regime has been proposing in the face of peaceful protests, now in their third month, is violence, violence that escalates and is “hybrid” in its nature: special forces’ attacks at the Maidan are combined with individual harassment and persecution of opposition activists and ordinary participants in protest actions (surveillance, beatings, the torching of cars and houses, storming of residences, searches, arrests, rubber-stamp court proceedings). The key word here is intimidation. And since it is ineffective, and people are protesting on an increasingly massive scale, the powers-that-be make these repressive actions even harsher.

More here.

Weekend Diversion: Make Yourself Hallucinate (Safely)

Ethan Siegel in Starts With a Bang!:

“Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming, ‘Wow! What a Ride!’” -Hunter S. Thompson

For those of you who’ve never experienced exactly what it feels like to alter your perceptions, and for those of you who have but don’t want to spend hours and hours experiencing the effects, your options have traditionally been limited. Perhaps a song might provide a window into the experience of blurred reality for you, such as Stereolab’s song: Hallucinex.

Thanks to the combined power of technology and our understanding of neuroscience (and perception), you don’t need drugs or to provoke your brain into releasing DMT. Rather, a simple visual pattern can induce temporary (lasting under a minute) hallucinations, safely and temporarily.

The visual patterns that can make us hallucinate typically involve tunnel-like perceptions, something that both math and neuroscience back up. In general, there are a number of things you can do to disorient your visual cortex, and your brain’s attempts (and failures) to adapt to the stimuli are what trigger the hallucination effect!

More here.

Syria’s Polio Epidemic: The Suppressed Truth

Annie Sparrow in the New York Review of Books:

One way to measure the horrific suffering of Syria’s increasingly violent war is through the experience of Syrian children. More than one million children are now refugees. At least 11,500 have been killed because of the armed conflict,1 well over half of these because of the direct bombing of schools, homes, and health centers, and roughly 1,500 have been executed, shot by snipers or tortured to death. At least 128 were killed in the chemical massacre in August.

In the midst of all this violence, it is easy to miss the health catastrophe that has also struck Syrian children, who must cope with war trauma, malnutrition, and stunted growth alongside collapsing sanitation and living conditions. Syria has become a cauldron of once-rare infectious diseases, with hundreds of cases of measles each month and outbreaks of typhoid, hepatitis, and dysentery. Tuberculosis, diphtheria, and whooping cough are all on the rise. Upward of 100,000 children are stigmatized by leishmaniasis, a hideous parasitic skin disease that flourishes in war. Many of these diseases have already traveled beyond Syria’s borders, carried by millions of refugees. Five million more children have been forced out of their homes but are still living within Syria, increasingly vulnerable to early marriage, trafficking, and recruitment as child soldiers.

And now polio is back.

More here.

phaedra 1962

foggy mountain breakdown

the man who sold his beard

Death by data: how Kafka’s The Trial prefigured the nightmare of the modern surveillance state

Reiner Stach in New Statesman:

“Kafkaesque” is a word much used and little understood. It evokes highbrow, sophisticated thought but its soupçon of irony allows those who use it to avoid being exact about what it means. When the writers of Breaking Bad titled one of their episodes Kafkaesque, they were sharing a joke about the word’s nebulousness. “Sounds kind of Kafkaesque,” says a pretentious therapy group leader when Jesse Pinkman describes his working conditions. “Totally Kafkaesque,” Jesse witlessly replies. If the word is widely misused, it is also increasingly valuable. Last year, when the attorney and author John W Whitehead wrote about the US National Security Agency scandal in an article headlined “Kafka’s America”, the reference to Kafka clearly made sense:

We now live in a society in which a person can be accused of any number of crimes without knowing what exactly he has done. He might be apprehended in the middle of the night by a roving band of Swat police. He might find himself on a no-fly list, unable to travel for reasons undisclosed. He might have his phones or internet tapped based upon a secret order handed down by a secret court, with no recourse to discover why he was targeted. Indeed, this is Kafka’s nightmare and it is slowly becoming America’s reality.

We live in a world of covert court decisions and secret bureaucratic procedures and where privacy is being abolished – all familiar from Kafka’s best-known novel, The Trial. This year marks the centenary of the book’s composition, though it was not published until after Kafka’s death, in 1925. Kafka’s texts age far more slowly than those of almost any other author of his era. In The Trial, we are drawn so compellingly into a story of pursuit and fear that it seems like a nightmare we all share, even though most people in the postwar west have not been subjected to anything nearly as extreme. Readers under communism, however, pictured a situation that they knew all too well, in which the fundamental rights of the individual had been stripped away. Many gravitated to a political interpretation of Kafka, bolstered by his friend and literary executor Max Brod, who had proclaimed Kafka a prophet.

Picture: Eyes in the sky: a security camera monitoring station in Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong

More here.

Her art belongs to Dada: Hannah Höch

Adrian Hamilton in The Independent:

“Hannah Höch the Dadaist” is the way that this German artist is usually pigeon-holed in art history. And indeed she was a leading member of the movement in Berlin in the 1920s, full of the calls for artistic revolution, the rejection of all that had gone before, the hectic partying and the collage works which made this movement so energetic and so productive.

…Born in 1889, Hannah Höch went through two world wars and the prolonged periods of economic distress and rebuilding which were their consequences. The experiences were quite different. In the intellectual ferment of Germany's Roaring Twenties which followed the First World War, the mood (except among those who had fought in it) was one of release from the past mistakes and clear horizons of a new world to be created out of its ashes. Hoch, who always tended towards anarchism rather than the communism of many in her circle, responded at first with some wonderfully witty and scabrous photomontages attacking bankers and ridiculing men in the family and in power. Adding watercolour and ink to collage, she seizes the spirit of the times with some joyously satirical collages of Coquette and the Singer and some open explorations of her own complicated sexuality.

A 10-year relationship with the Dutch Dadaist poet, Mathilda Brugman, and visits away from Berlin brought a change in mood as aesthetics. Höch became increasingly interested in collages as a means of representing the fragmentary and multi-faceted nature of a life, particularly a woman's. In a remarkable, and justly famous, series, (Untitled) [From an Ethnographic Museum], she uses the photographic images of primitive statues in museums and from magazines and pastes on contemporary heads and body parts. The result is an astonishingly subtle and challenging portrayal of what makes up the human and gender in the modern world. It's quite brilliant but also intriguing in its layered meaning.

More here.